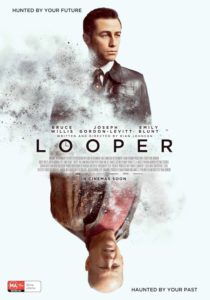

An intriguing concept that offers a unique twist on the time travel genre, but also spreads its ambitious ideas too thin.

Director: Rian Johnson

Writer: Rian Johnson

Runtime: 118 minutes

Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Bruce Willis, Emily Blunt, Jeff Daniels, Paul Dano, Pierce Gagnon

Distributor: Roadshow Films

Country: US

Rating (?): Worth A Look (★★★)

Bruce Willis is constantly being sent back in time. If he isn’t visiting his own past in 12 Monkeys (1995), or being visited by an 8-year old version of himself in Disney’s The Kid (2000), he is repeatedly forced to relive the 1980s through a series of creaky Die Hard sequels. Kind of like Quantum Leap, without the benefit of Harry Dean Stockwell as his guide. For writer/director Rian Johnson‘s third feature, following the acclaimed noir Brick (2005) and the schizophrenic The Brothers Bloom (2008), Willis is returned to the realms of science fiction in another missive on the duality of the self. Aided by some prosthetics, it-boy Joseph Gordon-Levitt picks up where Spencer Breslin left off in being incredibly disappointed in how the old man turns out.

In the not-too-distant future of 2044, economic collapse has led to severe social and urban decay. Sections of the population have developed telekinetic powers, and crime is rampant. Thirty years after that, time travel is invented but outlawed immediately. It is still used by criminal organisations to send their victims back in time to waiting ‘loopers’, who kill their perps in the past where they have no records or identity. Joe Simmons (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is one such looper, who collects his silver and lives a hedonistic lifestyle. However, when his future self (Bruce Willis) is sent back to be killed, both Joes are on the run from the mob when the younger Joe fails to carrying out the hit, or ‘close his loop’. The older Joe is on the hunt for a person he believes to be a future mob boss called The Rainmaker, and he suspects it is the young boy Cid (Pierce Gagnon), who lives with his mother Sara (Emily Blunt). Young Joe hopes to protect the boy and change the future for everybody.

The very idea of meeting your future self, or vice versa, is a powerful storytelling motif. Being able to change your destiny by informing your ‘other self’ of different decisions to make comes with the paradoxical realisation that you would not have that knowledge without the corresponding experience. Indeed, humans time travel every day by looking back in a nostalgic fashion, reliving past events through the distorted goggles of memory. We look forward to the future, imagining what will be, the most ambitious of us making those dreams a reality through sheer determination. Looper directly acknowledges this view of time travel, using a narrative tool where the actions of the past self immediately impact on the future self once they become aware of one another. Words cut into the an arm appear spontaneously on the corresponding appendage of a future self as a message or warning, and more importantly, memories of loved ones falter as new memories are created.

The notion that the ‘future is what we make it’ is not unique to Johnson or Looper, with parallels in other American time travel classics from Back to the Future (1985) or the more recent dramatic piece Safety Not Guaranteed (2012). This sits in contrast to the current run of UK’s Doctor Who series, where time is said to be a fixed entity once the future is acknowledged. While volumes could be written on what this says on the psyches of the American and British concepts of self-determination, but if you pick at the threads of Johnson’s film, there sits inside a minor parable about older selves betraying the ideals of youth. This is where the film is at its most interesting, wholeheartedly running (quite literally) with the notion of time travel paradoxes, Johnson crafting his story around these quagmires.

The other major success of Looper is in world-building, envisaging a future that is wholly familiar not simply due to the science fiction touchstones it marks off along the way, but because it’s also rooted in the preconceptions of the present. Technology is thrown in as a matter-of-fact detail about the world, just as it is a fact of our own lives. The supporting players, particularly in Jeff Daniels as the grizzled gangster Abe, world-weary from travelling from a future even stranger than the one we are presented. Indeed, we only glimpse the distant future in an alternative telling of Joe’s destiny, one that the older Joe wishes to maintain up until a point.

Yet if the strength of Looper is in its acknowledgement of the notion of duality, Johnson squanders its dramatic promise by getting sidetracked by other concepts that intrigued him along the way. A secondary sci-fi concept acts as a deus ex machina to get the script out of a few tight spots, and when it unleashes its full fury, it takes the film into places that bring a shark back in time to jump over itself. It erodes the impact of the more straightforward and clever take on time travel, and is almost as if Johnson was so keen to leap into sci-fi that he threw all of his ideas in at once. An action-drama masquerading as a sci-fi film, there are some provocative concepts in Looper, just don’t study them for too long.

Looper was released in Australia on 27 September 2012 from Roadshow Films.