Director Darren Aronofsky is not known to play by traditional Hollywood rules. After attending both Harvard University and the AFI, Aronofsky went on to create his debut feature π (or Pi) for a mere $60,000. The film, about a mathematician on the brink of insanity, defied expectations and sold to Artisan Entertainment for $1 million, grossing three times that at the box office and garnering wins at Sundance and the Independent Spirit Awards.

His follow-up, Requiem for a Dream, generally received universal praise from critics, but divided some over its depiction of drug use. Eschewing the chance to direct Batman Begins to try his hand at the metaphysical with The Fountain, telling the story of a man trying to save his life over the course of 1,000 years. Yet it was with 2008’s The Wrestler, a comeback film for both the director and actor Mickey Rourke, that Aronofsky finally gained the attention of the powers that be, despite a lack of Best Picture nomination at the Academy Awards.

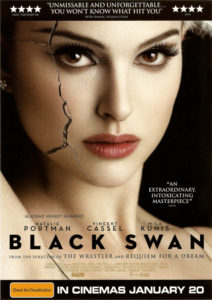

Black Swan follows a New York ballet company preparing for a production of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Dancer Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman, Brothers) is desperate to prove that she can play the coveted lead role. Pushed by her overbearing mother (Barbara Hershey, Albert Schweitzer), a failed dancer, and the presence of newcomer Lily (Mila Kunis, The Book of Eli), Nina manages to convince Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel, Mesrine) to cast her, replacing embittered prima ballerina Beth MacIntyre (Winona Ryder, Star Trek). However, as Thomas pushes Nina to embrace her sensual nature and her darker side to play both the White Swan and her twin the Black Swan, she begins to tap into a fractured part of her psyche that threatens to envelop her.

Black Swan is an intense, erotic and thrilling masterpiece. Like a puzzle that needs to be slowly unpacked, the film is deep and rich and demands multiple viewings to fully uncover all that the script has to offer. Weaving in elements of Swan Lake‘s tragic narrative, the film explores the very nature of duality and in the process delivers the most powerful interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s works to date. Portman’s Nina has a singular quest in the film: to be perfect. Yet in the pursuit of this single-minded motive, we are given a shockingly stark depiction of the price of that perfection. Viewing the world through the eyes of Nina, our perspective is often myopic and claustrophobic. Indeed, much of the film either takes place in the rehearsal space or one of three rooms in Nina’s shared dwelling with her mother. As Nina grows increasingly paranoid about the motives of practically everyone around her, the audience cannot help but share this paranoia.

The fear of being replaced, especially at something that we are skilled in or has been the focus of one’s entire life, is instantly relatable to almost anybody. Picking up any tabloid magazine in the supermarkets, and the media’s obsession with (and demand of) its stars’ perfection grows increasingly manic. The film merely focuses that microscopic self-examination of potential flaws and confines it to the closed world of ballet dancing, serving to intensify it all the more. Nina’s mother has seemingly forced her failed dreams on her daughter, and treats her with suspicion, so it is only natural that Nina’s perspective (and ours by extension) is skewed by this. Even as the world begins to spiral out of control, it all seems so perfectly natural. Perhaps this is what will leave audiences the most unsettled long after they have left the theatre.

Drawing upon his own cinematic legacy – along with others who have explored the nature of duality (Ingmar Bergman, David Lynch, David Fincher) – Aronofsky tells a story that can only be told in the cinematic medium. Taking on board the seemingly impossible task of making a film about ballet thrilling, Black Swan does far more than fill the spaces between Fatal Attraction, Fight Club and Showgirls (a broad set of spaces if every there was one). That said, it knowingly plays on those conventions that we have become used to in a thriller, the psychological buttons that tell us that we are being manipulated. Even if you figure out fairly early on that all isn’t as it seems, it is only in smashing conclusion that audiences are let in on how far down the rabbit hole they have been taken. Separating itself from lesser thrillers along the way, the film is a visually striking representation of the director’s own continued quest for cinematic perfection. Bringing to the table all of the tools the medium has to offer, Aronofsky spares no tricks in convincing us of the continually fractured nature of the world he has created.

The performances are powerful, with Natalie Portman giving one of her finest roles to date. Portman, like the character she portrays in Black Swan, often gives technically good performances, but not exactly ones overwhelming with emotion. Sometimes this is the fault of the material (most notably the woeful wooing scenes in Star Wars – Episode II: Attack of the Clones), and at other times is simply a range limited by her arm’s-length coldness (such as The Other Boleyn Girl). Yet there is a hidden darkness and past mental instability in her character that is often only hinted at throughout her award-worthy performance in Black Swan.

Both Portman and her co-star Kunis are literally physically transformed by the picture, with the latter reportedly dropping a large amount of weight to convince as the dancer. If the film has something in common with Aronofsky’s previous outing The Wrestler, it is the unbelievable physical strain that the performers put their bodies through for the unsuspecting public. Through a seamless combination of practical and special effects, and the actor’s own exercises, we can almost feel every bone in their bodies aching. Rounding out this trinity of excellent actresses at the top of their game is Winona Ryder. Although only appearing in a small role, Ryder as the ageing prima ballerina gives one of her best performances in recent memory, and is perhaps even more memorable than Kunis.

This will no doubt be flocked to (pardon the pun) by audiences around the world, but don’t expect this to be a pleasing experience for all audiences. Despite what it may say on the back of the box, dancing plays a limited role in the film. It is the human relations that are the real ballet here, playing a delicate balancing act between fracture psyches, sexual repression and release and outright hostility between the dancers. It is unlikely that a film this powerful will overwhelm you for some time to come.

Black Swan is released by Fox Searchlight in Australia on 20 January 2011.