With the release of the Coen Brothers’ True Grit, a remake of Henry Hathaway’s 1969 John Wayne late-vehicle, the American western has been brought back into focus. Set to become the second highest grossing western of all time, behind Kevin Costner’s revisionist western Dances with Wolves, True Grit may be just the blockbuster the genre needs to put gunslingers back on the map. Yet this revival doesn’t just hark back to the 1960s, but back to the birth of cinema itself.

In literature and in film, the western genre is one of the truly original contributions of the United States to the canon. Coming out of the stories that are as timeless as the land itself, the genre has evolved and grown over the years, with as many peaks and troughs as the great state of Arizona. New generations of filmmakers rebelled against what had come before, and styles influenced by European filmmakers and Japanese samurai films invariably changed the genre forever. Yet there is something timeless about the cowboys of old that draws audiences back again and again.

Join us for the first of a three-part retrospective on the American West. This series hopes to cover some of the trends in westerns over the last 100 years, and highlight some of the major (and minor) films in the canon. In this part we explore the earliest days of western film through to the changing of the old guard in the middle of the 20th century.

The first shot

Some of the first films ever made were tales of the old west, although it wasn’t quite as old then. Of the earliest bits of celluloid to come out of the states were shorts containing Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley themselves, by which stage the Old West had already become a piece of popular entertainment. One of the earliest seminal American films is Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903). Not only did the film effectively launch the western genre to cinema audiences, it was one of the first examples of narrative storytelling on film. Prior to that, film had largely been used to simply record life in all of its banality. The film shows a surprising amount of sophistication in this regard, containing one of the most famous shots in motion picture history as of the robbers points his pistol directly at the screen and fires. This level of audience involvement was the start of so many things to coming century of filmmaking.

A few notable westerns were made in the years afterwards, and G.M. Anderson of The Great Train Robbery would star in over a hundred films as Bronco Billy from 1907 onwards. Serials such as The Santa Fe Trail (1923) and features such as Victor Fleming’s The Virginian (1929) and even Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) peppered the silent years of cinema. However, it wasn’t until the late 1930s that the Western would be elevated to almost mythical status thanks to two men who went by the name of John.

The two Johns on the horizon

Born Marion Robert Morrison, better known to the world as John Wayne or simply “The Duke”, the man who would go on to define ‘cowboy’ for many had a rather inauspicious start to his career. A former football player, Wayne got bit parts in early John Ford films, a director whose partnership with Wayne would define both of their destinies, and forever establish them as benchmarks for many westerns that were to come. Wayne’s first starring role was in The Big Trail (1930), one of the earliest widescreen movies shot on both 35mm and 70mm by Raoul Walsh, who would become a well-established western director and one of the founding members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). The casting of the then unknown Wayne may be one of Walsh’s crowning achievements, but The Big Trail was significant for a number of other reasons. The clothing worn by the actors, especially Tyrone Power, was far more authentic and gritty, and shooting on location across five states (including California, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming and Oregon) for stunning vistas was bold, especially in the economic slump of the Depression. It truly marked a turning point for the genre, but it would be almost a decade before another truly seminal piece of western filmmaking would come along.

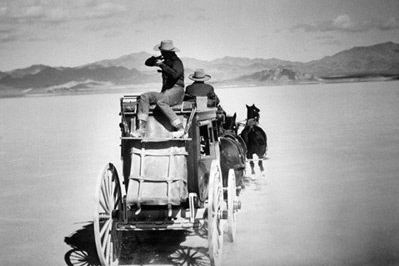

Stagecoach (1939) is often considered to be one of the finest examples of the western in the first half of the 20th century, and marked one of the great collaborations between Wayne and Ford. J.A. Place (1974, p.32) notes that “it is often regarded as the standard against which others of the genre are measured”. The superficially simple story of nine people taking the stagecoach journey between Tonto and Lordsburg, where there has been “Indian trouble” afoot, can be described as a morality play of the clearest order. Transplanting theatre archetypes to the screen, each character is a representative of a human frailty or strength. Wayne’s Ringo is perfect, “appearing like a god out of the desert (Place, 1974, p.34).

The film also marked Ford’s first use of Utah’s Monument Valley as a backdrop, the first of ten times he would use the location. (So much so, there is a popular tourist area called John Ford Point in the Valley). In Stagecoach, it is a location, rather than the icon it would become from at least My Darling Clementine (1946) onwards. In that film, Ford’s casting of the landscape in his distinctive lights and shadows definitely has a quality to it that makes it a silent, albeit highly visible, tertiary character. He expands the legendary tale of Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral to legendary proportions, far more so than the George P. Cosmatos’ later Tombstone (1993) or Lawrence Kasdan’s Wyatt Earp (1994). Henry Fonda as Earp is as clean-cut as they come, but almost paralysed by fatal indecision. Indeed, Hamlet is directly referenced in the narrative. (It would be the stark antithesis to a character he would play almost a quarter of a century later in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West). Yet we also witness here an evolution of the character of the west, from merely a backdrop for a fight between the ‘bad’ Indians and the ‘good’ settlers. The landscape was becoming as legendary as the characters themselves, and perhaps it was simply because it too was disappearing into history.

Don’t get your guns

Ford’s collaboration with both Fonda and Wayne would see some terrific collaborations in the genre over the years, yet they weren’t the only gunslingers in town. In Destry Rides Again (1939), James Stewart is directed by George Marshall (How the West Was Won) as a deputy sheriff who refuses to wear a gun. Sticking to the letter of the law, he manages to keep peace in the town with words, perhaps making him one of the more unconventional heroes of the era, in an excellent piece of cinema (despite the presence of Marlene Dietrich as a singing barmaid). By way of comparison, The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) – another Henry Fonda vehicle, this time directed by William A. Wellman – follows Destry Rides Again‘s call for the rule of law over the power of the gun, an argument that holds incredible significance when one considers this film was released while the United States was in the middle of a war.

The Ox-Bow Incident sees a formation of a lynch-mob based on the rumour that a local rancher has been killed by a group of rustlers. Some passing strangers are thought to be the rustlers, and only one man – the fighting saloon barfly Gil Carter (Henry Fonda) – is willing to stand up for them. Eventually, the strangers are hanged by the mob, before they find out that not only have the rustlers been caught, but the local rancher is still alive. Buscombe (2005, p.195) describes this as “a key film in the history of the Western, one of many that showed that the Western – previously a genre with low cultural prestige – could take on important issues”. It was a significant departure from the ‘might makes right’ attitude of the earlier films, and like Howard Hawks/Arthur Rosson’s Red River (1948) it consciously pushed against the old guard, quite literally in the case of the latter by casting Montgomery Clift as the son who doesn’t want to follow his father’s (John Wayne) ways.

The first half of the 20th century would end with a pair of highly regarded Westerns: Rio Grande, the third part of the Ford/Wayne “Cavalry Trilogy” (along with Fort Apache and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)) and Winchester ’73 (both 1950). The latter was the first of eight collaborations between James Stewart and director Anthony Mann, who would also give us strong Western entries Naked Spur (1953) and The Man from Laramie (1955). Like Destry Rides Again and The Ox-Bow Incident before it, Winchester ’73 speaks to the power of the gun, and more specifically the power of the titular gun that changed the fortunes of all who came into its possession. It would be the powerful shot that would signal the need for a number of gunslingers to hang up their colts, with a number of heroes riding out into the sunset in the years that followed.

Sunset on an era

Keller (2001, p.27) talks of the pre-1980 westerns as roughly falling into two categories. The “affirmative” type of western, such as My Darling Clementine and Red River, through which there is a kind of “regeneration through violence”, and the “critical” kind. To this last category we may add High Noon (1952), where we saw a “lessening of the hero’s stature, making him a figure of pathos, not tragedy…” (Pye, 1996, p.19). Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) stands alone against a posse of outlaws bent not only on his demise, but on ruling the town as well. In a stark contrast to The Ox-Bow Incident almost a decade before it, the mob refuses to stand up with Kane, forcing him to race against the ticking-clock to prepare for the arrival of the villain on the noon train. The ticking clock throughout the film heightens the tension and reminds us of the inevitable, but the clock could almost be ticking down to the demise of the traditional western hero.

Shane (1953) may well give us this symbolic death on-screen, in “sure the most iconic…Western that burns itself into our memory, the Western no one who sees it will ever forget” (Pomerance, 2005, p.294). Stranger Shane (Alan Ladd) settles in with a family of homesteaders, deciding to help protect them from the cattlemen who want to move in on their land. Drawn to the homesteader’s wife, and developing a mentor relationship with the young son of the couple. Noted New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther commented at the time that Shane “contains a disturbing revelation of the savagery that prevailed in the hearts of the old gunfighters, who were simply legal killers under the frontier code”. The young boy of the film loses his innocence with the audience, and as Shane rides off into the sunset through a graveyard, we are left to ponder the fate of our hero. Yet most will know on some level that there is really only one fate for the likes of Shane.

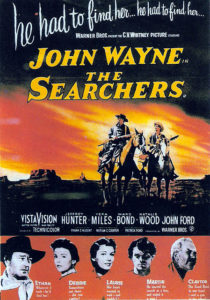

Named the Greatest American Western of all time by the American Film Institute (AFI) in 2008, The Searchers (1956) was not even nominated for an Academy Award in its day. Perhaps this was indicative that the tin stars were fading in the popular spotlight, with the likes of pseudo rape-fantasy musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) winning the popular and critical votes of the time. Yet there was far more to The Searchers than just the sum of all the parts of both Ford and Wayne’s careers. Noted critic Roger Ebert comments “In The Searchers I think Ford was trying, imperfectly, even nervously, to depict racism that justified genocide; the comic relief may be an unconscious attempt to soften the message.” It may not have been the first time racism was depicted on-screen, but it was another sign of the turning of the tide. The days of cowboys versus ‘Indians’ were numbered, and the revisionist view of the western myth was just beginning…

In Part 2 of my exploration of the Old West on Film, we’ll take a look at the turning of the tide as filmmakers rebel against not only the old world ways of telling a story, but in the very values of the United States. The western myth is revised, and gets a little bloodier, we take a journey into the surreal and the Man With No Name drifts into town.

References

Buscombe, E. (2005). The Ox-Bow Incident (1943). In S.J. Schneider (Ed). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. (Revised Edition, p.195). Sydney: ABC Books.

Crowther, B. (1953) Shane. In The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2011, from http://www.nytimes.com/1953/04/24/movies/042453shane.html

Ebert, R. (2001) The Searchers. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved January 17, 2001, from http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20011125/REVIEWS08/111250301/1023

Keller, A. (2001). Generic subversion as counterhistory: Mario van Peeble’s posse. In J. Walker (Ed). Westerns: films through history. (pp. 27-46). New York and London: Routledge.

Place, J. A. (1974). The Western Films of John Ford. Secaucus: The Citadel Press.

Pomerance, M. (2005). Shane (1953). In S.J. Schneider (Ed). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. (Revised Edition, p.294). Sydney: ABC Books.

Pye, D. (1996). Introduction: Criticism and the Western. In I. Cameron and D. Pye (Eds) The Movie Book of the Western. (pp.9-21). London: Studio Vista.

Related Links:

Comments

1 response to “The evolution of the western: Part 1 – the last gunslingers”

[…] The evolution of the western – Part 1: the last gunslingers […]

[…] The evolution of the western – Part 1: the last gunslingers […]

[…] Tarantino was no doubt conscious of in Kill Bill: Volume 2 (inspired by everything from Leone to The Searchers). Composer Marco Beltrami was actually a student of Morricone’s, and his equally haunting […]

In The Ox Bow Incident, Henry Fonda isn’t the only one to stand up to the mob, it’s the characters of Daley and the preacher who do. Fonda is opposed to the mob but he keeps silent. That’s kind of the point of his character – silence in the face of tyranny.