Abbas Kiarostami’s 1997 feature A Taste of Cherry shared the Palme d’or at Cannes with Shohei Imamura’s The Eel, and was not only praised for its interesting use of audio and visual techniques but for the nature of the public/private relationship that emerges as one person gives a lift to another in a car. His follow-up The Wind Will Carry Us similarly followed the repetitions of everyday life, observed with a tranquility that Kiarostami has come to be associated with. Over the course of the last decade, the Iranian director has experimented again with conversations in cars in Ten, filmed a UN commissioned documentary about Uganda (ABC Africa), and was involved in the collaborative film Tickets with Ken Loach and Ermanno Olmi. With Certified Copy (Copy Conforme), Kiarostami shot and produced his first feature film outside Iran and once again returned to the concept of the conversation.

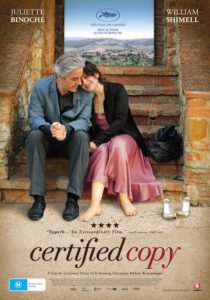

James Miller (British opera singer William Shimell) arrives in Tuscany to promote his new book on the subjective value of art in history, and is soon joined by antique shop owner (Juliette Binoche, Summer Hours). The pair begin with an awkward encounter in her store, but begin their conversation as she drives them around the Tuscan countryside in a kind of “deliberate aimlessness”. As their talk moves from the value of art to the bonds of marriage, it becomes possible that the two of them have met before. Or have they?

Certified Copy opens with a three-minute shot of microphones, and doesn’t get much more exciting after this. The film is deliberately intellectual, and on this level, it has been quite consciously and impenetrably set up to not be enjoyable either. That is not to say there is not beauty or levity in the piece: the stunning Tuscan vistas are the stuff of middle-aged wet dreams, and the leisurely pace of the film allows one to soak up much of this beauty. It would be a perfect picture of serenity if it weren’t for the two people who stand between the camera and those backdrops for much of the film. On the one hand we have the unnamed character played by Binoche, who seems to be incredibly angry at virtually everything that Miller expresses. This is not surprising given that throughout the narrative he, despite some possible character revelations in the second half of the film, is one of the most annoying prats to ever stand in front of a beautiful landscape. If familiarity breeds contempt, then this pair are clearly more knowledgeable of each other than their initial encounter lets on.

When it becomes obvious that there is more to this relationship than meets the eye, it is not entirely clear what it is the film wants us to think or believe. The earlier musings on taking art at face value are perhaps a clue to the true nature of their relationship, and whether we are viewing an approximation of one or a certified genuine original marriage that has gone horribly wrong somewhere is a question left hanging. Just as Blue Valentine (or even Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) explores the effects of falling out of love, and the devastating aftershocks of a (possible) tragic event, Certified Copy is an example of what happens when it all goes wrong. Yet Kiarostami is not interested in the ‘hows’ and whys’ necessarily, but rather what the conversation can reveal about a person, including a lengthy one using his favourite setting of a car. In the course of an afternoon with these people, and it does feel like a rather long visit, we slowly learn tiny bits of information about the fractured nature of their relationship, if a relationship ever existed. Is it, like a painting they ponder at one point in their travels, merely an imitation of something observed in life? We may never know, and while Kiarostami seems content to explore the philosophy of riding in cars with boys, the rest of the audience may find it impenetrable.

[stextbox id=”custom”]Although it may be a film that is never meant to be fully understood, it also limits it from being fully enjoyed. The kind of pure intellectual cinema that is a rarity in the 21st century, but doing anything more than appreciating this fact will be a frustrating experience for most.[/stextbox]

Certified Copy was released on February 17, 2011 in Australia by Madman Entertainment.