A frustrating and sporadically beautiful film, that remains as impenetrable as the activities it depicts. Best watched with a cup of tea.

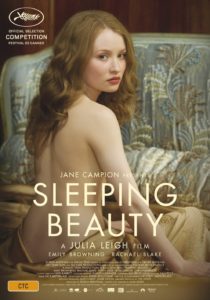

Australian novelist Julia Leigh marks her debut as a filmmaker with Sleeping Beauty, based on her own screenplay about a young student drawn into a world of desire. Allusions to fairy tales become pronounced as Leigh’s tale unfolds, in a film that played in competition at Cannes this year, marking Leigh as a voice to watch, even if what she is saying isn’t all that interesting.

Australian novelist Julia Leigh marks her debut as a filmmaker with Sleeping Beauty, based on her own screenplay about a young student drawn into a world of desire. Allusions to fairy tales become pronounced as Leigh’s tale unfolds, in a film that played in competition at Cannes this year, marking Leigh as a voice to watch, even if what she is saying isn’t all that interesting.

University student Lucy (Emily Browning) works a series of small-time jobs to to support her studies. Detaching herself from those around her, she really only connects old friend and reclusive addict Birdmann (Ewen Leslie). Lucy answers a classified ad for a high-class waitress to work at private functions. Under the tutelage of Clara (Rachael Blake), the ingenue exploits her unique beauty for the benefit of high class clients over a series of intimate encounters that escalate rapidly.

There will be few films as divisive as Julia Leigh’s Sleeping Beauty. Taking a sleep-inducing drug, Lucy (known in her new life as Sara), she remains unconscious while elderly men have their way with her. High-class concierge Clara has a simple rule for her clients: no penetration. Leigh seems to have issued the same guidelines to her audience, challenging us with her emotionally distant meditation. Reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut it has more in common with Catherine Breillat’s work, in particular Anatomy of Hell, not to mention Edmond Vadim Glowna’s similarly themed House of Sleeping Beauties from back in 2009. Indeed, Breillat has a released a TV movie called The Sleeping Beauty, which is due for a theatrical release later this year. Both directors have an aim of subverting the male gaze an achieving this through shock and awe. As with Breillat’s Anatomy of Hell, the male form is something grotesque when compared with the flawless beauty of Browning. Yet she, much like the film itself, is something to be admired and observed, but there is no hope of ever getting closer to her. The only hope we have of ever gleaning any human connection is via the character of ‘Birdman’, except he too is ill-defined and tokenistic in his characterisation.

Consequently, despite being weighed down by some clunky dialogue and narrative choices, betraying Leigh’s novelist origins, the photography by Geoffrey Simpson is actually quite breathtaking. However, this too is a barrier to any kind of connection it may hope to achieve with an audience, as it is like a piece of art hanging in a gallery behind a velvet rope: tantalisingly close, but oh-so-far-away. The stiffly framed shots are incredibly precise, and much like the similar European formality of Michael Haneke, it aims to lull into a false sense of serene security before ‘shocking’ us with its conclusion. However, neither the beauty of the sets nor its frequently undressed star will be enough to maintain audience attention over the course of this slow-moving and often cumbersome collection of moments and scenes that having little connection beyond being in the same film. While Leigh, much like Breillat or Haneke before her, undoubtedly has a strong voice, it remains largely unclear as to what she is actually trying to say by the time the end credit creep around.

Sleeping Beauty was released on 23 June 2011 in Australia from Transmission.