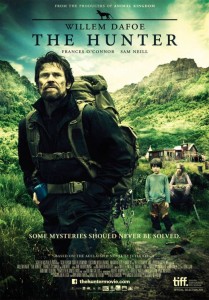

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Hunter (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”220″]

Director: Daniel Nettheim

Runtime: 101 minutes

Starring: Willem Dafoe, Frances O’Connor, Sam Neill

Distributor: Madman

Country: Australia

Rating: Better Than Average Bear (?)

[/stextbox]

When Sleeping Beauty was released earlier this year, Julia Leigh proved that as a filmmaker, she makes a great novelist. Managing to churn out a technically beautiful, but ultimately lifeless, film about a pseudo-prostitute, it was perhaps wise that someone sporting the screen credentials of TV’s crime-drama Rush , along with the producers of the over-praised Animal Kingdom, was brought in to helm the adaptation of her first novel The Hunter.

Martin David (Willem Dafoe, Daybreakers) is a mercenary sent from Europe to the remote bushland of Tasmania, with a highly lucrative offer to track down what is believed to be the last remaining Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger. Boarding with the family of Lucy Armstrong (Frances O’Connor, Blessed), the self-medicated and practically comatose mother of two precocious children, Martin learns that her evironmentalist husband has gone missing. Martin soon encounters the hostilities of the local industry workers, convinced that he is another ‘greenie’ sent to shut them and their highly profitable operation down. Yet with the potential goldmine of a Thylacine at stake, Martin can afford few distractions in reaching his goal.

The Hunter is something of a curiosity, with all of the setup of a major thriller, but none of the pacing. Nettheim, by way of Alice Addison’s screenplay, has in fact crafted an incredible intimate film set against the impressive backdrop of Tasmania’s uncharted wilderness. It is true that the film emphasises the mystery and thriller elements of the novel, setting up a sinister shadow organisation from the start that continually rears its head in unexpected places. Yet in the casting of Dafoe, one also gets a physically compelling presence, one that intrigues simply by his ‘otherness’.

Dafoe stands out in a sea of familiar local faces that also include Sam Neill, and of course O’Connor, as much as any international award-winning actor would on the Australian scene. He also brings with him a commanding presence of being the ultimate outsider, and one that could legitimately go against the tide of aggression he is met with in the film. He did play Jesus in a Martin Scorsese film, after all. When the film shifts gears as Lucy awakens from her hibernation, an intimate family drama unfolds. The strength of Dafoe’s performance is in his flexibility, and his ability to allow us to believe these dual personas.

Shot entirely on location in Tasmania, cinematographer Robert Humphreys (A Heartbeat Away) does not always make the most of his stunning landscape, shooting it in cold and sterile blues and greens, perhaps to reflect the clinical mind in which Martin views this strange new world. It is still cast as a mysterious place, shades away from being an Australian gothic piece like Kriv Stender’s Lucky Country, and the slow-pace of the film only adds to the mystery of the landscape. The finding of the Tasmanian Tiger is secondary to the journey, both physical and personal.

[stextbox id=”custom”]The Hunter is an intriguing, and often gripping film, with an intimacy that is rare in such a thriller. Filled with mesmerising imagery, it is much like footage of the last Tasmanian Tiger, in that it will haunt you long after you’ve left the cinema.[/stextbox]