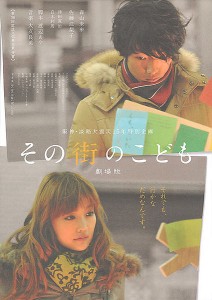

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Town’s Children/Surviving the Quake (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Tsuyoshi Inoue

Runtime: 79 minutes

Starring: Mirai Moriyama, Eriko Sato

Country: Japan

Rating: Worth A Look (?)

[/stextbox]

On 11 March 2011, the magnitude 9.0 Tōhoku earthquake hit the east coast Japan, and the resulting tremor and tsunami caused the deaths of thousands of people, and billions of dollars worth of property damage. It was the worst earthquake to hit the country in its recorded history, but it was also the most recent in the dozens of severe quakes that have rocked the island nation over the last century. One of the most devastating in recent years was the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake, or Kobe Earthquake, that took the lives of 6,434 people. The Town’s Children or Surviving the Quake (その街のこども) deals with the aftermath of that tragedy on the fifteenth anniversary of the event.

On the eve of the memorial service for the victims of the Kobe Earthquake, Yuji (Mirai Moriyama, 20th Century Boys) finds himself strangely compelled to get of his Hiroshima bound train at the Shin-Kobe station. He encounters a flirtatious and cute Mika (Eriko Sato, Goemon), who has been similarly drawn back to the city. After missing the last local train, they decide to walk the distance to the memorial and find themselves wandering the streets, bringing up old memories of their childhood. Both were survivors of the Kobe Earthquake, and both have unresolved issues that will be exposed before the night is through.

Already enjoying a successful NHK screening back in 2010, director Tsuyoshi Inoue reworks his original television footage into this feature length film for a theatrical and festival release earlier this year. The Town’s Children has a definite pace to it, with the single-night setting reminiscent of Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, but without the romantic undertones. Here it is not love that it slowly being uncovered, but personal loss and emotional scars. Making the film even more poignant is the casting of the two leads: stars in their own right, both Moriyama and Sato are Kobe bore witness to the quake, with Kobe-native Moriyama having personally witnessed the disaster as a child.

Aya Watanabe’s (Boat, A Gentle Breeze in the Village) script is a talky affair, and many will be tested by the leisurely pace at which the duo make their way to their ultimate destination. However, Inoue has intercut his own footage with archival pieces showing the wreckage of the city immediately following the quake, contrasting this with what Mika describes as a city that looks “brand new”. Inoue’s docu-drama technique means that each new corner his characters turn opens a floodgate of memories and an increasing awareness that neither of them are alright fifteen years on. Yet as they eventually reach the memorial, the anxiety may have been uncovered, but it is not a necessarily cathartic process for everyone.

The leads seems to be at ease with one another, and after some initial awkwardness, it is entirely believable that these two would want to spend a night with each other. More importantly, it is easy for the audience to spend the time with them. Mika’s brashness is grating at first, but it gives way to a vulnerability that Yuji’s dismissive facade tries not to betray. There are a few moments when scenes drag on a little longer than they should, but this does little to diminish the observational power of this simple setup, accompanied by a moody score from Yoshihide Otomo that sounds like it is channelling Joy Division at times.

The Town’s Children is a timely film for Japan, and any country that has suffered recent tragedies. It asks the biggest question of them all: where do you begin to pick up when your entire world seems to have collapsed around you? As Japan still picks up the pieces after the most recent devastation, all the while living under the shadow of the next “big one”, The Town’s Children is a reminder that life goes on, even at its most painful.

[stextbox id=”custom”]The Town’s Children may not be a “big” film, but this doesn’t mean that it isn’t an important one. Pacing issues aside, it is mandatory viewing for anybody who has suffered loss.[/stextbox]

The Town’s Children is screening on 27 November (Sydney) and 30 November (Melbourne) 2011 at the 15th Japanese Film Festival in Australia.