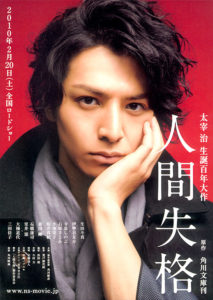

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Fallen Angel (2010)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Genjiro Arato

Runtime: 134 minutes

Starring: Toma Ikuta, Yusuke Iseya, Michiyo Ookusu, Shinobu Terajima

Country: Japan

Rating: Wait for DVD/Blu-ray (?)

[/stextbox]

Osamu Dazai is considered to be one of the noteworthy writers of the 20th century in Japan, and one of the most infamous literary figures in the country’s history. His life, fueled by prostitutes and a constant battle with alcohol and depression, infused his frequently semi-autobiographical works, leading to his suicide in 1948. During this period, the writer was at his most popular, with the release of his post-war novels Villon’s Wife and No Longer Human, the quasi-autobigraphical novel that was being serialised at the time of his death. The latter forms the basis of The Fallen Angel (人間失格), and adaptation of the Dazai novel from director Genjiro Arato (Akame 48 Waterfalls).

Born into a wealthy family, Yozo Oba (Toma Ikuta, Hanamizuki), the emotionally detached child is told by friend Dakeichi that he will draw beautiful pictures and attract a number of beautiful women. When he meets the older Horiki (Yusuke Iseya, 13 Assassins), and is taken to the Blue Flower Bar run by Madame Ritsuko (Michiyo Ookusu, Someday), he soon falls into the life he was promised. However, he soon tires of this life, and when he meets kindred spirit Hisako (Shinobu Terajima, Caterpillar), the go down the same rabbit hole.

Sharing thematic similarities with 2009’s Villon’s Wife, and adaptation that came out the same year as filmed versions of Shayo and Pandora’s Box, there is a sense that we’ve been through this all before. As is the case all over the world, once film producers get a whiff of a back-catalogue of potential adaptations, there is no stopping them. Remember the Jane Austen craze? Given how depressing Dazai’s novels are, even a few years of distance can’t completely lift the black veil that hangs over the suicide centric works of this seminal writer, and many of the scenes look and feel as though they stepped straight out of Kichitaro Negishi’s Villon’s Wife. The Fallen Angel offers the same emotional distance between the audience and its characters that earlier Dazai adaptation did, following a group of characters that are seemingly destined to be forever condemned to a type of living purgatory or end their lives trying to escape.

For any artist, or sufferer of depression, there will undoubtedly be some sense of affinity with the narrative. What is absent from the film is the strong narrative voice that comes with the novels, the author’s cathartic act of working through the pain by expressing his feelings in prose. Even in its extended state, The Fallen Angel does not have sufficient scope to explore the mind behind the madness. We see the descent without any corresponding window into the root causes of the downward spiral. There are moments, of course, when we get tantalisingly close to this fractured life, especially when Oba reveals his artwork to a friend. The haunting vision of a twisted human is, we realise immediately, his inner self. Yet this barely manages to encapsulate a life, especially one that was tortured by suicide. Like Tadanobu Asano in Villon’s Wife, idol Toma Ikuta is a handsome young pretty boy, and there is no sense that his life would be filled with anything other than beautiful women.

Dazai’s novel explored the post-war mental health of a nation when it was originally published, and Arato does a fine job of physically recreating this period of transition between pre-war Japan and the hi-tech cities of the future we know and love today. Yet this is only surface-level sheen, much like the portrayal of Oba himself. This is not a deeply disturbed individual, it’s a bratty one who gets a bit stupid after a few cold ones. If any more insight is needed, a trip to your local pub may suffice.

[stextbox id=”custom”]The Fallen Angel explores alcoholism, art and suicide and may drive audiences to at least two of those.[/stextbox]