Ivan Sen drew on personal experience for his debut feature film Beneath Clouds, filmed on a $2.5 million budget in rural New South Wales. The film went on to international acclaim, screening at Sundance in 2003 and winning the Premiere First Movie Award at the 2002 Berlin Film Festival and the 2002 Best Director Award at the Australian Film Institute Awards.

Ivan Sen drew on personal experience for his debut feature film Beneath Clouds, filmed on a $2.5 million budget in rural New South Wales. The film went on to international acclaim, screening at Sundance in 2003 and winning the Premiere First Movie Award at the 2002 Berlin Film Festival and the 2002 Best Director Award at the Australian Film Institute Awards.

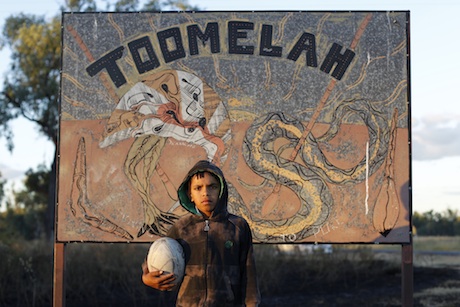

Sen has continued to explore the issues impacting on Indigenous Australians, through a series of short subjects and documentaries, as well as a feature he shot in the US last year called Dreamland. With Toomelah, Sen returned to the familiar Toomelah Aboriginal Mission in New South Wales where he used to spend time as a child. Already experiencing international success with the film, including screening at the 2011 Cannes International Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard program and in competition at the Sydney International Film Festival.

Toomelah tells the story of a remote Aboriginal community through the eyes of a 10-year-old boy Daniel (Daniel Connors), who regularly skips school and wants to be part of the gangs and drug trade that goes around the township. We watch Daniel’s life become increasingly difficult as he deals with his dysfunctional family, including his mother’s addictions, his estranged alcoholic father and his Aunt, who returns to the mission after being forcibly separated from the family as a child. Isolated and vulnerable, Daniel must make some difficult decisions concerning the future of his life.

We were lucky enough to get to chat with the director about the film and his upcoming detective Western Mystery Road. We need to thank Curious Film and Tracey Mair at TM Publicity for the opportunity.

I’d read that you’d written the script from your memories of Toomelah, and I guess what sparked your inspiration to make the film in the first place?

Well, I’ve always wanted to make a film out there because some of my earliest memories come from there. I’ve never lived there, but I used to go there all the time…But my mother grew up there and all her family come from there so there’s always been a connection there. As a result, I’ve always wanted to go back there and do something, make this film, a drama. It took a long time work out a method in which to do it, but the story came from a very intense observation period where I went out there for a few weeks and just followed a few teenage boys around and followed the little boy around who played Daniel and wrote down everything I saw, even the dialogue I heard. All of that all came together in the screenplay.

You’ve touched on that a little bit already, but the cast in the film are quite amazing, and I understand a lot of them are fairly new to acting. How did you go about choosing your cast?

When I realised that I had to make the film in a certain way, which involved me going out there by myself and camera and some equipment and getting them to help, the local people helped make the film. Once I’d worked that out I had to try and make it up as as I went. I had to try and get these people who had never acted before to give performances. They weren’t improvising they had to say the lines which I had written in the script. But in saying that, all of the lines do come from that observation period where I had heard so much of this dialogue getting thrown around. When they did have to say the words it came out quite naturally because those words come from that place and not my imagination.

The technique I developed involved not getting them to read the script, but getting them to actually know what the dialogue is. I just wait until the moment we were filming and they would call the lines out and they would actually call them back. That was the technique I would use all throughout the filming, because I was by myself. I had one eye through the camera, and one eye on the script and call out lines and the name of the people, as well as keeping an eye on the lighting and the sound and all of that.

You’ve mentioned it a few times already, the fact that you were out there with basically no crew, working with a community. Was that a conscious decision from the beginning to get the right mood for the film, or was that something that came naturally from your scouting period?

I had made an experimental film before that called Dreamland, and that involved me going out to Nevada making films with a couple of actors just with myself. That gave me the confidence to attempt the same kind of approach with Toomelah. But after I wrote and completed the research period, that’s when I realised that if I bring a crew out here the kids are just going to be too self conscious and they’ll kind of clam up. The only way around that was for me to just do it alone, or take the crew out there for 6 months or something and allow them to get used to all the actors.

I guess the next thing I want to ask flows on from that. Filming in an Indigenous community, what kind of reactions did you get? I know you obviously spent a bit of time scouting, but what kind of response did you get from the community to your feature film?

It was a very positive one, and they were very enthusiastic about the whole idea of me making a film there. Every day, I’d have people coming up to me asking if they could be in it, and everybody wanted to be involved in it. I didn’t really get any negative comments about me being there making a film, and we had the community screening there last week out there on the football field. It was an amazing experience. All these families came together, and the laughing started at the beginning and went all the way through it, and they just couldn’t believe they were seeing their own experience on the screen…reacting strongly to seeing each other on the screen as well, and laughing and carrying on. I did get a feeling that they could sense some kind of validation that their life had been captured in some kind of way.

Yeah, and the film does capture a lot of the issues for Indigenous Australia over the years, and very much has a look at the past in present, it touches on the Stolen Generation and alcoholism, but left very much to audience interpretation as well. How do you see this film, and even film generally, in this dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia?

Well, there’s a highway that goes past Toomelah and its always full of tourists and truck-drivers going from Queensland to Victoria, and New South Wales. It’s like that feels like mainstream Australia that road, but they never really have an idea of what goes on in Toomelah, which is just off the road. I think something like the film can give wider Australia a glimpse into what’s its like growing up and living on this community. But in saying, for Indigenous people it’s a real – because they know about these things – it’s a form of entertainment, and after last week I could sense that its a real inspiration for the younger Aboriginal kids as well.

It is another chance and another step forward for awareness of the wider public of Indigenous Australia.

You’ve obviously approached a lot of these issues in the past in features and documentaries. When you are approaching something like this in narrative form, as opposed to a documentary, how do you approach things differently?

Every project is different, and all the issues that do come up in the film come up from a natural process of creating the screenplay in a way which involved me going and around just observing Daniel in day to day life, and also the life of teenagers around there…All the issues just come out of that as a natural process. When Daniel wakes up in the morning, he has to decide whether he goes to school or not, in reality and you know, he’s got the education coming in there, and he has to decide on what he’s going to eat, and that’s going to impact on his health. When we were there last week, there was a couple of stolen motorbikes, so Daniel has to decide whether he’s going hoon around on that or not and become involved in the whole cycle of crime which involves a lot of young kids as well. So it’s just a very natural result of being intimately depicting someone’s life in a place like that.

But in saying that, the effects of the Stolen Generation was something that I consciously put into the script, because it effected my grandmother directly. It very closely emulates what’s in the film.

Did you find a film like this difficult to get made in Australia?

No, there’s a lot of support there from Screen Australia, and also state bodies. I think audiences have been opening up to Indigenous stories of late, so there is some audience interest there and the Australian Film Commission in the ’90s, which was an early form of Screen Australia, they were very supportive about developing Indigenous filmmakers back in the early ’90s period, so we’re just starting to see the results of that coming through now.

Where do you see other filmmakers picking up from where you’ve left off? You’ve chosen Toomelah as an example of a type of community, and you’ve already mentioned it’s an inspiration…

I’m not sure. I’m actually planning on heading back out to Toomelah to do some workshops with kids, because they have a very keen interest in movies generally. They’re fans of cinema. So I’m looking to go out there and develop the kids’ interest in film, and just spend some more time with teenagers out there, because film is such an accessible thing these days, people can have a go at it themselves on their mobile phones, and edit it on the phone. But even people involved in this film – Daniel really wants to continue with his acting and also Chris as well, who played the gang leader guy. So I’ll do what I can to help Daniel go forward with his potential career.

Having introduced a group of people to acting, were there any more ideas for future ideas or projects coming out of that? You’ve already mentioned a few things.

I think I’ll integrate – Daniel has an amazing smaller brother, he’s an extraordinary character and I think he’ll be an amazing actor. I’m making another film called Mystery Road which will shoot in April next year. It’s more of a genre film. It’s going to be a murder-mystery, and I’m planning on using some of the actors I used in Toomelah and taking them across and integrating them into that film.

Fantastic. Can you tell us a little more about that.

Yeah, it’s a murder-mystery. It’s about an Aboriginal detective who has to solve the murders of these young Aboriginal girls found under the highway and out of town, and he has to thread his way through the race relations of the town and the local drug scenes just to solve the cases. It will have a very strong Western influence to the film as well. It’s a bit of a cowboy, I call him a cowboy detective. [Laughs]

Oh, fantastic. I think we should have more Westerns in Australia.

Yeah yeah. And there’s a big shoot-out in the film at the end, which I’m looking forward to doing.

I’ll look forward to seeing it as well! I guess that leads me on to something I always like asking people, which is your influences. You’ve just mentioned you have a bit of a Western influence…

Yeah, that film has a big influence from No Country for Old Men, the Coen Brothers film. I think something I really appreciate about that film is that it’s really quite a layered film, quite artistic, but also it’s a commercial film as well and it’s made quite a lot of money and had an impact on the international audience. That’s kind of the area where I want to start heading towards.

With this film Toomelah…did you draw on any particular influences there?

Not really, not at this stage. I probably just looked to my own experiences of making Dreamland, and also all the documentary work I’ve done over the years. Probably tapped into that a lot. But in saying that, years ago I’ve always felt that stuff that Lars Von Trier was doing with his intimate approach where he is holding the camera and being very direct with his actors, that is a very intimate way of getting truthful performances.

One thing you mentioned a moment ago was in pushing Australian film overseas, in connection with genre films. Do you think that’s the way forward for Australia cinema?

Yeah, well that’s the obvious kind of approach. I’m not sure about Australian films as a whole, or even the industry…

Maybe you in particular, how would you like to approach it?

I was just talking to someone the other day about commercial movies, and I really don’t think they need to be so bad. There’s a lot that can be done with commercial genre films in a way that hasn’t been done before, and also done with sensitivity. As well as having all of the elements that make them a genre film at the same time. There’s room in Australia to play with that as well.

Thank you very much. I’m really looking forward to that Western.

Yeah, that’s going to be an amazing experience. It’s very kind of old style, and very restrained.

Where’s that shooting?

Around north-west New South Wales and also into Queensland, and certainly the outback of Queensland as well.

Ivan, thank you so much for your time.

No worries. Cheers.

Toomelah is released in Australia on 24 November 2011 in Australia from Curious.