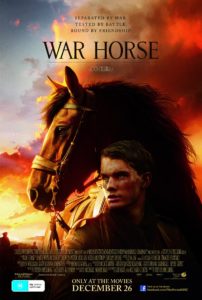

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”War Horse (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Steven Spielberg

Runtime: 146 minutes

Starring: Jeremy Irvine, Emily Watson, Tom Hiddleston

Distributor: Disney

Country: US

Rating: Worth A Look (?)

[/stextbox]

Based on Michael Morpurgo’s young adult novel, War Horse was adapted into a critically acclaimed stage production in 2007. Although tapping into the very human emotions that surround the effects of war, Morpurgo was originally responding to the massive loos of horse life in the First World War, an estimated 10 million horses on all sides. Indeed, of the million horses that were sent overseas from the UK, only 62,000 returned, the rest either killed in action or for meat. A story of this scale of sentimentality was bound to attract the attention of Hollywood, and naturally the king of sentimental war stories Steven Spielberg.

After bonding with his unconventionally determined horse in Devon, Albert (Jeremy Irvine) is separated from the animal as it is shipped off to the front at the start of the First World War. The horse begins an journey that will see him serve both the German and English sides during the war, while Albert has his own odyssey across the front. The horse will meet a number of individuals whose lives he will touch, showing the commonalities that both unite and divide the world during times of conflict.

The film opens with a drawn-out and sentimental opening sequence, in which Albert ultimately bonds with the horse in an extended plot about tilling the soil on his father’s (Peter Mullan) failing farm, despite protests from a skeptical mother (Emily Watson). It is only when the British army is introduced, via Captain Nicholls (Tom Hiddleston) and Major Stewart (Benedict Cumberbatch), that a lightning bolt is sent through the film and some impact is felt for both the human and animal characters. Hiddleston’s penetrating gaze captivates for his brief run on screen, and one almost wishes that we could follow him for a little longer. However, it is quickly established that all humans in the film are transitory, and some humans have more of a lasting impression than others.

Spielberg, already adept at showing us the Second World War from all angles, brings us a very different vision of the first Great War initially, including the involvement (however briefly) of the Indian army and a particularly striking sequence in which the British stage a bloody-minded frontal assault on the enemy. In this one sequence, Spielberg reminds us that the First World War changed almost everything humans knew about combat. The animals in the story are seen as the greatest victims, for while the humans made the decision to follow what they have done in the past, the horses had no option but to follow the humans. When we switch to the German side, and for the first time see the devastating number of fallen mounts, the horrors of war are brought home in a way that stacks of human bodies may have ceased to do for cynical and war-weary audiences.

Janusz Kamiński’s photography has become synonymous with Spielberg, having photographed all of the latter’s films since 1993’s Schindler’s List. Taking notes from Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front through to National Velvet and virtually any other animal film of the era, there is an old-fashioned sweeping lens that bursts the film out from the page and stage to a suitably enormous scale. As such, the film is undoubtedly beautiful, from its sun-stroked skies to the mangled trenches of the Western Front. Yet the photography is not the only old-fashioned thing about the film, with the odd decision to give all non-English characters accents rather than have them speak in their native tongues. Even Indiana Jones‘ Nazis spoke German, and this seems out of step with modern filmmaking and audience expectations.

Spielberg’s conscious tugging at the heartstrings ironically creates an emotional distance from what should be some of the more powerful sequences in the film. For example, one sub-plot with an elderly man and his daughter should elicit some surprise when it reaches its conclusion, but the overt emotional manipulation seals their fate from their first introduction. Not helping matters is John Williams score, which is about as subtle as a sledgehammer. From the opening scenes, it never gives the audience room to come to terms with events, but rather constantly hits them over the head. It is a problem that plagues an otherwise moving film, and one that for many may inhibit accessing what is an often beautiful and well-acted piece.

[stextbox id=”custom”]A flawed but consciously emotional film, giving a storybook quality to events that should never be glossed over. Still a well-made piece, but never gets the mix of its individually strong parts right.[/stextbox]

DreamWorks’ War Horse is released in the US on 25 December and on 26 December 2011 in Australia from Disney.