To celebrate the release of Hugo, our latest list takes a look back at some of the seminal silent films from the early days of cinema.

To celebrate the release of Hugo, our latest list takes a look back at some of the seminal silent films from the early days of cinema.

This is certainly not a “best of” list. As we never like to just make things easy on ourselves, our lists are not necessarily top five lists, they are more or a less a list of film recommendations within the theme of the list. Naturally, there are scores of important films from the early years of cinema, but these are five from different genres: sci-fi, Western, horror, documentary and surrealist.

Many silent classics have been lost to the ages, but thanks to the wonder of the Interwebs, many of them now survive in digital form and are freely available to the public. While the people who made these films couldn’t have possibly imagined their films being distributed across a global information network, as these five films show, there were no limits to their imagination.

A Trip to the Moon / Le Voyage dans la lune (Georges Méliès, 1902)

Some call this the first sci-fi film, and in many ways it is. Yet it is also significant for being one of the first major uses of animation and special effects all blended together. Based on Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and H. G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon, it is largely a series of scenes strung together, but each has its own innovative technique. Perhaps most famous for shooting the “Man in the Moon” in the eye with a rocket.

Fun fact: This later featured in the music video for Queen’s song “Heaven for Everyone”, served as the basis for a recreation in The Smashing Pumpkin’s award-winning video for “Tonight Tonight”. That video was directed by Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, who would later go on to helm Little Miss Sunshine. From the moon to the sun!

The Great Train Robbery (Edwin S. Porter, 1903)

One of the earliest seminal American films is Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903). Not only did the film effectively launch the western genre to cinema audiences, it was one of the first examples of narrative storytelling on film. Prior to that, film had largely been used to simply record life in all of its banality. The film shows a surprising amount of sophistication in this regard, containing one of the most famous shots in motion picture history as of the robbers points his pistol directly at the screen and fires. This level of audience involvement was the start of so many things to coming century of filmmaking.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Weine, 1920)

Some may point to Nosferatu, but for us it has always been Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari). Like the film itself, the poster uses the angular features of German Expressionism, and the impossible angles and long shadows that come with it. This wasn’t just limited to the photography, but the sets themselves had unusual angles, and the actors moved about with intentionally jerky and angular movements. Some even say that this film introduced

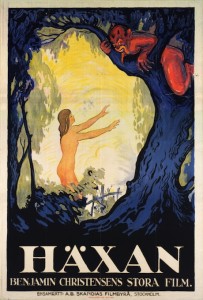

Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (Benjamin Christensen, 1922)

Director Benjamin Christensen was light-years ahead of the game, creating a horror piece that has genuinely got a few scares under its belt. The demon birth scene may be laughable, but the sabbath has all manner of creatures and animal-like beings dancing in the fire in a display that is both surreal and chilling.

BitsFact: This was the first film we ever reviewed on The Reel Bits, back when it was called The DVD Bits Blog. A lifetime ago!

Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel, 1929)

A cloud cuts the moon. A razor cuts an eyeball. A dead donkey is dragged along, and an army of ants invade someone’s palm. What does this all mean? Does it have to mean anything? Un Chien Andalou (or An Andalusion Dog) is an intense, almost physical, experience. The pure visual feast that Buñuel served up would be inspiration to filmmakers as diverse as Buster Keaton (who had in turn influenced Buñuel), Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch. Indeed, while the latter often claims not to be a film buff, his physically involving (and sometimes exhausting) abstractions often conjure up the spirit of Buñuel. It is no surprise to learn that it was banned and cut in some countries.

While Buñuel’s later films are technically superior, this one is considered to be such a surrealist masterpiece largely due to the involvement of Salvador Dalí. He would join Buñuel the following year for L’Âge d’or (Age of Gold), as well as collaborations as diverse as the dream sequence in Hitchcock’s Spellbound and the Walt Disney animation, Destino (which would not be released until 2003). Here, however, the pair seemed to work together to produce something that was as close as possible to an unfiltered representation of their dreams in the cinematic medium. To try and analyse the film any more would be like trying to pin down a cloud.