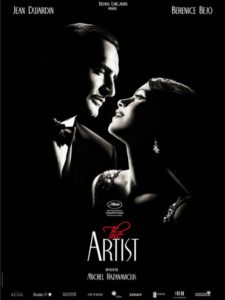

Celebrating cinema’s history by perfectly recreating it, Michel Hazanavicius’ silent gem speaks volumes about the capacity to find great joy in simplicity.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Artist (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Michel Hazanavicius

Writer(s): Michel Hazanavicius

Runtime: 100 minutes

Starring: Jean Dujardin, Bérénice Bejo, John Goodman, James Cromwell, Penelope Ann Miller

Distributor: Roadshow

Country: France

Rating: Certified Bitstastic (?)

[/stextbox]

Despite the fact that silent films went the way of the dodo when sound was introduced over eight decades ago, a fascination remains with what could be argued is the only purely visual form of cinema. Michel Hazanavicius, best known for James Bond spoofs OSS 117, rides a wave of critical acclaim with The Artist, a film that reaches our shores on the back of victories in virtually every awards ceremony known to humankind. Like Martin Scorsese’s similarly nostalgic Hugo, it asks audiences to time-shift back to a period when great technological changes meant the beginning and ends of careers for a great many people.

In 1927, silent film star George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) attends the premiere of his latest film A Russian Affair, when a chance encounter with would-be starlet and fan Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) lands her on the cover of Variety with the headline “Who’s That Girl?”. When Miller auditions for the role of a dancer, Valentin convinces a reluctant Kinograph studio boss, Al Zimmer (John Goodman), to give her a role in the film. Yet when sound becomes a reality, and Zimmer shuts down all production on silent films, the skeptical Valentin soon finds himself a dinosaur in Hollywood. As Miller’s star continues to rise, Valentin is on the outs, especially when the stock market crash of 1929 hits.

The period that The Artist covers has been recreated so well in the perfect Singin’ in the Rain (1954), and the inability for a silent movie star to move on in a changing world was captured so hauntingly by Gloria Swanson in Sunset Blvd. (1950). Which is what makes Hazanavicius’ film such a monumental achievement, in not only writing a love-letter to an era of major transition in Hollywood, but in using the language of the time to do so. The Artist, for those not in the know, is shot almost entirely as a silent film. It is black and white and without dialogue, framed in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio of the day. This could have quite easily been seen as nothing more than a gimmick, were it not done with such affection on the part of the creative team and the talent, all invested in tipping their collective hats to the history of cinema.

Hazanavicius’ script doesn’t attempt to hide its tributes to Hollywood of yesteryear, weaving its way through a fairly familiar A Star is Born-style narrative, with visual nods to more films than we care to list here. As the film culminates in its melodramatic climax, the swelling strains of Bernard Hermann’s score to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo add a familiar emotive response to those in the know, especially given the more sinister themes behind Hitchcock’s masterpiece. Yet do not mistake The Artist for a mere pastiche, or a simple glorification of an art form that died with the introduction of sound. Hazanavicius could have chosen any form in which to tell his story, but the particular language of silent film necessitates a different mindset from the audience. As cinema has evolved over the years, our brains have been hardwired to watch and consume in different ways, and this format forces us to slow down, absorb the imagery and more importantly, the wonderful characters at the heart of the film.

It would be difficult to find a more perfect on-screen couple than the dashing Durjardin and beautiful Bejo, who exude charm and grace in every frame. This is best demonstrated in a dance sequence in which they repeatedly play out a filmed scene where there are supposed to awkwardly exchange partners, but intentionally keep flubbing it to make each other laugh. Yet there are some insightfully dramatic moments, including one scene where Valentin can hear sound for the first time in all things, only his own voice excepted. There is also exceptional gentility in James Cromwell‘s loyal butler to Valentin, a cigar chomping hilarity to John Goodman’s naturally flamboyant silent performance and a clearly Singin’ in the Rain inspired Missi Pyle. Special mention must also go to Uggy, the little dog who steals every scene it is in.

Beyond a few draggy moments at the top of the elongated third act, it is quite difficult to conjure up any faults in the film. Indeed, for anybody who has ever been enthusiastic about films or simply wants to experience the pure joy of experiencing silent comedies at their height, then The Artist is deserving of every accolade that comes its way. As the punchline of the film rolls around, in some of the few moments that feature dialogue, it will be impossible to get that big sloppy grin off your face.

[stextbox id=”custom”]Witty, musical and magical, all without uttering a single word, Hazanavicius does the impossible by not only recreating a period film, but the experience of watching the film in that era.[/stextbox]

The Artist is released in Australia on 2 Februrary 2012 from Roadshow Films.