The Working Dog team have been behind some of Australia’s biggest hits on the small screen and at the cinema, from their earliest television days of The D-Generation and The Late Show through to films like The Castle and The Dish.

In the 12 years since The Dish, the creative forces of Santo Cilauro, Rob Sitch, Jane Kennedy, Tom Gleisner and Michael Hirsh have produced television gold in the form of talk show The Panel, improv comedy Thank God You’re Here and political satire The Hollowmen. Now their first theatrical outing since 2000, Any Questions for Ben?, explores the quarter-life crisis that is a reality for every young global citizen.

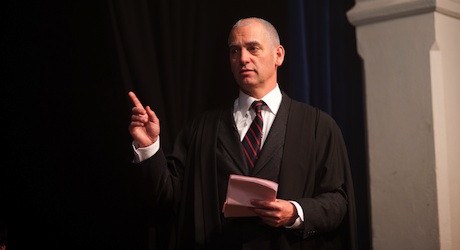

We were lucky to sit down with Rob Sitch in Sydney last week, and discuss his thoughts on the film, the crisis of choice, breakfast cereal, Melbourne, Yemen and his plans for the future.

We need to thank Roadshow Films for all the access given to the cast and creative team of this film, and of course, Mr. Sitch for his time and generous answers.

Any Questions for Ben? is released in Australia on 9 January 2012 from Roadshow Films. You can also our full review.

Listen to the interview above, or read the transcript below.

RG: Well, congratulations on the film.

RS: Oh, thank you.

RG: It’s a fantastic film I really enjoyed it.

RS: When did you see it?

RG: I saw it on Monday night.

RB: Oh great! Was it with a big audience?

RG: It was a pretty large audience.

RS: Comedies are made to be seen with an audience.

RG: This is the thing. I was speaking with Daniel [Henshall] and Jodi [Gordon] this morning, and they were saying one of the things that attracted them to working with you was, one the Working Dog name, and two the chance to try out comedy in that environment. When you come to a story like this which is a real mix of comedy and pathos, what was the spark for you in driving this story?

RS: I don’t think…I think if you literally just make it comedy, somewhere around the 45 minute mark it becomes inconsequential. You’ve got to somehow…that’s why comedies love a great character. Kenny or Crocodile Dundee. Or even Darryl Kerrigan funnily enough, it’s a family, but it’s a big character. It’s a character that carries you, and you need to know what happens to big – when I say big, I don’t mean hammy characters – I mean, you go “Wow”. You get hypnotised into wanting to see what happens to them. And I think comedy is that, but this is an ensemble. So I think you can’t just make it a series of misunderstanding and mishaps. You’ve got to – the audience has to know you’re heading somewhere, and not that we’re headed somewhere didactic.

We’re just saying, that this guy’s logical and in the end when he flips out – we were saying there is a manifest difference to being in your 20s now than there was twenty, definitely thirty years ago. The world is your oyster your oyster, you know, people – you’re a kind of a global, if you want to be, a global citizen. You’ll find yourself working in Berlin as much as you’ll find yourself working down in Bondi. The world is populated by these roving tribes of people who travel odd Africa, and have lots of relationships. And we knew of the concept of the mid-life crisis, of the quarter-life crisis, so we thought what a great clash. But if you pick a person with a perfect lifestyle, it’s hard to derail it. If he loses a job, he just gets another one. And then one day, we have a bolt of lightning and just went: school. You go back to school and you’re not cool, you’ve wasted ten years. Or you think “What’s gone on? What? What do you mean? Surely I’m cooler than I, you know?” And then the headmaster says, well I got the order wrong. And that doesn’t help him either. And he did get the order wrong. You don’t put a person working in the humanitarian United Nations, and then go “So tell us about vodka”. He’s dead at that point. So it’s not a clear answer…The ten year mark. If you turned up triumphantly, and it went badly, it would throw him. It throws him just enough.

RG: Yeah, I was going to ask you that. It is very difficult to have a character who is very successful, and he’s dating another woman every night and he’s got the cars. Did you every worry at all in that process that people were not going to relate?

RS: Yeah, it’s a worry but you’ve got to be a bit truthful. You can’t say he’s really got a heart of gold deep down. He doesn’t. He’s selfish. Great guy, and great company, and the girls going into a relationship with him think this is going to be great, but he just doesn’t mean it. But he’s got a great friendship group, and then he gets thrown. Funnily enough, the tennis player is based on a true story I know, and I thought that’s another great derailment because she’s more global than him, and is ready to move on quicker than him. And he’s going “Whoa!”. So I just wanted a taste of his own medicine, and that throws him again. So it’s all like that, but one of the observations that I think it’s under-remarked upon, is that a lot of the big things in life that used to be in your 20s – choosing to get married, until recently having kids in your 20s is standard – people now instinctively I reckon if you did a poll of people living in the inner city, they’ve penciled that in for their 30s.

So you’ve got at least ten clean years, and that’s fine: your job and your career, and education and all these sorts of things and travel, but when you get into a pretty serious relationship, both people are seeing it going ‘our timing’s wrong’. It’s a weird thing, that we’ll probably not going to – we might go out for years, but we’re probably not going to end up together. So that timing, that’s a funny – to have a series of relationships knowing they’re not going to last – even though you don’t go into it saying that. It’s a funny, so there’s a timing issue coming up when maybe 50 years ago the first serious relationship you had was when you go ‘That’s when you get married’. Whereas now, people have lots of serious relationships, and then you’ve got to somehow navigate your way out of that mindset, and go ‘No, now I actually have to choose’. I think that’s a very interesting phenomenon.

RG: It’s interesting that you should mention choice, as I remember reading something recently saying the fact that we have choice is making us miserable.

RS: There is an interesting psychological school of thought now that is truly examining that choice makes you less happy and more depressed. A guy wrote a book about it, about the breakfast cereal, he realised that there used to be one form of it…

RG: And he was happy with that…

RS: And he was happy with that. And then he becomes unhappy because he goes ‘Maybe I should have got it with honey crunch’ or maybe I’m having a lesser version of it. Maybe I’d enjoy it more if I got the extra fibre.

RG: It ruins your whole day then.

RS: It spoilt his…it’s spoilt. And what happens is with more choice, we grieve for the choices…and that’s one of the themes of the film. You have to give up to grow up. That choice is sometimes an illusion, and you can only pick one thing.

RG: On the subject of choice, was Josh Lawson always the…

RS: Yeah. We’d said to Josh, we thought he was particularly talented. We’d first met him through Thank God You’re Here, people said…we were looking for people who had fast sharp brains. Someone said to us, you have to see this Josh Lawson. And he hadn’t really done anything, and we met him and he was probably the most naturally gifted person who could do comic material that we’d met. He just continued to amaze us, so we made a note to ourselves that the next movie we made we’d write with the lead actor in mind from a very early stage. So all the little cadences were written for a person that we knew would do it this way, or that way. So after maybe only two drafts we got got Josh, he was in Australia, and said go and read it. We said it won’t be ready, but we just want to hear your voice in it. So we went off and did ten more, so he was in from a quite early stage. And because he’s in every scene, so it has to be him. You never feel like he’s reading a script, it’s got to be his thoughts. So it has to be, it’s got to just come out of him. So we started that very early.

And then Rachael [Taylor], I’d suggested Rachael very early. I think she was away between movies and came in. So that part was pretty easy. And Dan [Henshall], I didn’t know Dan. Jane Kennedy was doing the casting, and he’d actually just started doing Snowtown. So it was funny, because the part is really loving and warm and he’s currently playing a serial killer. And Felicity [Ward] had never done a film, but we’d seen her do a few comic things and thought that she was made for it…But it was fun casting in that age group…because cumulatively it just added a whole bunch of energy. It was really good.

RG: And when you’ve got a really large ensemble cast like that…how tightly scripted is the film?

RS: It’s very tightly scripted. It really easy. That’s the only thing I insist on. It’s like a musical score, you just do it that way. But that’s why you need people who can do it. I mean, there’s always script issues. They say that doesn’t flow out of that, or we love, if you’ve identified a flaw, we love rewriting it. During rehearsal, Tom Gleisner would sit there ready, swap that word with that, you know. The only thing was at the end of scenes we’d give people, mostly Josh, a licence to add something. Just maybe to keep his brain alive. But a lot of, maybe a dozen of, those little things make it into the film. But he would always do it syllable for syllable, but once it was over he’d flick something in at the end.

RG: I guess the other major character in the film is Melbourne. Was it important for you to have it as a Melbourne-based thing?

RS: No, it was important that we knew the town where we were going to base it, so if I lived here I’d set it here. But there’s little nuances to a city. Because if you don’t know a city, you’ll end up looking like the postcards for the city and that’s not…it’s a different place. In fact, we were about to shoot in one laneway and people said yeah, because the Melbourne Tourism Board is shooting there tomorrow, and we went “Kill the location”. We’re too late. It was a lovely area, but it was probably too neat. As in, eh, we might get sprung there. But it’s things like major events, that’s what people do. There were complications, but you’ve got to go to the tennis and shoot there. It’s only on two weeks a year, so that’s difficult. You know, there’s probably no-one at that age that doesn’t attend the RC Spring Carnival one day in those four days. So that’s a rhythm of life in Melbourne. So we knew all that, and we knew that there’s a time where you walk around in Melbourne and people walk around in big hats all over the city. Going to the tram station…So there’s those little rhythms to the city if you understand them well. I don’t know what it is in other cities.

So also because Melbourne’s changed massively in the last 20 years, because there was a policy to get people back living in the city. I guess the government thought they were going to get retired couples, but young people moved back in and really revamped the city in a really exciting way. It’s really changed. It’s become a sort of – I was talking to the Lord Mayor about this the other day [Laughs] – I ran into him the other day coming down the street. I asked him, do you get lots of enquiries from overseas. He said all the time. The least interesting part of Melbourne ended up being the indispensable part, and that was all these laneways that really had rubbish skips in them. Low rents, and the creative kids come in and reinvent it…and suddenly the high-rent strips look dated, and everyone was off in these little lanes. So it’s become a sort of a worldwide…poster child…for redeveloping inner urban. There’s a lot of inner urban areas in the world that have been hollowed out…Whether the lessons they’re learning from it are the right ones, but it is funny. You go to Melbourne on the right night, and it’s got a buzz that’s quite addictive and you can see why.

I would go into the city and just walk around and…try and get…those moments when it feels like that, and when it doesn’t feel like that. Some nights it doesn’t feel buzzy at all. It feels very, very dull. It’s little things I noticed, like some nights, there’s no cleaners. Or the lights in all the buildings are not on. It’s like Melbourne’s asleep. Others, everything’s going on, and then you realise that a thousand taxis in the city, and they’ve all got headlights on and it makes it. If there’s not enough cars in the city, it doesn’t buzz. That was funny…it took me a while to work out when to shoot and how to shoot, and it was slowly like a Rubik’s Cube, it would work out in little bits and pieces. When is it magic and when is it not? There’s a time of night at the Comedy Festival when there’s queues of people around the Town Hall. The queues are gone, but you remember the night when it’s full of people, so you have to capture what your mind is remembering. You have to plan it so you come at a time when it looks like what your memory is.

RG: That was a city you are very familiar with, and with this film you do travel a bit.

RS: Yeah, well I know Queenstown pretty well. Queenstown is like, again, it’s like, you know it’s a great city. I’ve never been there in the ski season, only to shoot this. But I know all that heli-skiing and all that world, it was interesting to see the guys that had not been there. Josh and Christian hadn’t been there. Just everyone was blown away by it. It’s just a feeling that its a great holiday, and we needed a place where he’d go…and delay it. But he goes there against this magnificent backdrop, he starts obsessing over his choice, grieving for the choice he made. So then we had to go to Yemen.

RG: So, yeah, I was going to say was it important to you to not cheat that thing and actually go to those locations?

RS: You couldn’t cheat that. We tried to. No, for security reasons, but Morocco didn’t look like Yemen. The reason we didn’t pick Morocco is that everyone’s been to Morocco. Well, it feels like it. We had to pick a country…that sounds very exotic. But it’s got a big diplomatic corps of UN, and American government and all that. All those countries in the capital have big diplomatic corps. All South East Asian countries have big ex-pat communities. Not so much Yemen. So then we had to go there. So the warnings were getting worse and worse and worse. So we just had to bite the bullet. We got a security expert, who advised us and came with us.

That post credit scene wasn’t personal experience was it?

Funnily enough, life imitated art. When Josh came back, he was queried, ‘Why did you go to Yemen?’. It was pretty bizarre. I didn’t know, I didn’t even think of it. But yeah, he was queried over what was your purpose of travel to Yemen. But you say to make a film, and you have photos on your iPhone. No really…People are more interested than suspicious I think.

Just finally, it might too early to say given you’re still on the tour for this, but what plans do you have coming up for the near future?

I wouldn’t like to leave it as long to make another film, but I’ve gotten reminded of why you don’t do them a lot. [Laughs] Because they are quite involved. But I’ll do a little bit of television this year, and I think something that involves writing. I do. Someone said to me ages ago that at the end of the day, it’s what you write sort of thing. It’s possible true for me anyway. I don’t think I’d be satisfied if it didn’t require some form of writing.

Thank you so much for your time.

Pleasure. It’s nice to meet you.