David Cronenberg returns for a spanking good time in his first film of the decade, opening the cases files on the relationship between Freud and Jung.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”A Dangerous Method (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: David Cronenberg

Writer(s): Christopher Hampton

Runtime: 94 minutes

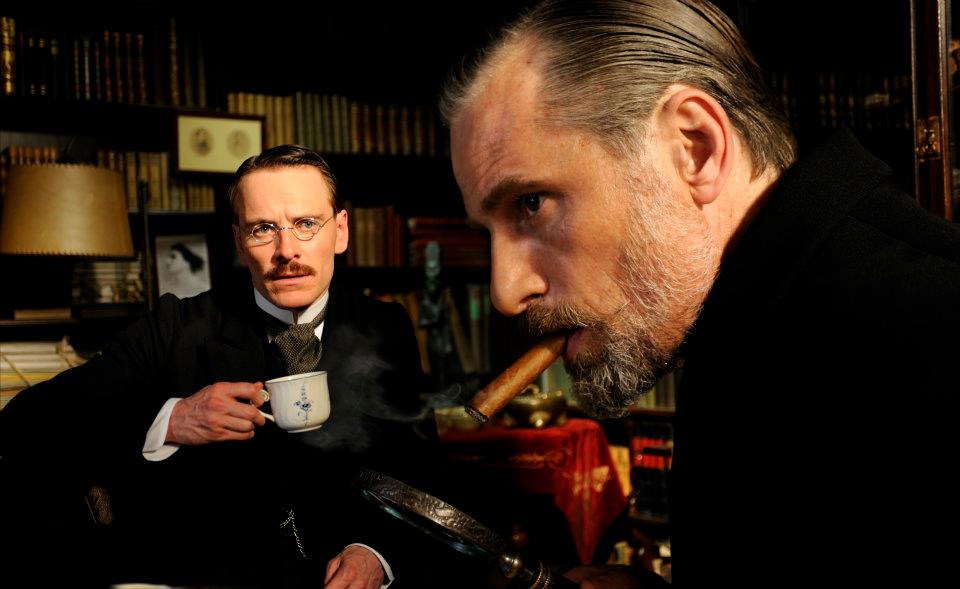

Starring: Michael Fassbender, Kiera Knightley, Viggo Mortensen, Vincent Cassel

Distributor: Paramount/Transmission

Country: UK

Rating: Better Than Average Bear (?)

[/stextbox]

Since Canada’s David Cronenberg began making moves away from the “body horror” genre, which he pioneered in the 1970s and perfected with Shivers and Videodrome, his source material has become even more eclectic. As he struck a winning partnership with actor Viggo Mortensen in comic book adaptation A History of Violence and Russian mob picture Eastern Promises, his films have become increasingly layered and sophisticated. Cronenberg’s work has always explored the limits of the human mind, and a biopic on two of the world’s most famous analytical psychologists perhaps reflects the director’s own recognition of the basis of many of his nightmares and dreamscapes.

Just before the start of the First World War, Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) stands on the verge of breakthrough in analysing his mentally ill patients with the so-called “talking cure”. He spies an opportunity to test out those theories with Russian patient Sabina Spielrein (Kiera Knightley), an intensely neurotic case who is aroused over physical acts of violence. As Jung begins an intense intellectual relationship with his mentor and eventually friend Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), he also begins an explicit affair with Spielrein, who is destined to become one of the first female psychoanalysts. This unconventional triumvirate challenge each others ideals, and ultimately leads to a convergence in the profession.

Christopher Hampton’s script, based on the on his own National Theatre play which was in turn based on the John Kerr novel A Most Dangerous Method, is an engaging character study of a moment in history. Hampton takes this event and spins it into a dramatic retelling of the beginning of an era, or the end of one if you prefer. The skills of the twin brains of Hampton and Cronenberg working in their Freud/Jung symbiosis, probably without the sexual dysfunction and extended episodes of spanking, weave what could have been an endlessly talky stage-focused piece into a dramatic interpretation of the realisation of a new set of ideas.

Fassbender earnestly throws himself into the character of Jung, remaining aloof and distant with his wife at times, loving at others, even when he is engaging in unfettered acts of lust with Knightley. Mortensen, knowing his way around a Cronenberg film by now, effortlessly slides into Freud, drawing out each line as if perched on a throne looking down at disciples. Trying a Russian accent on for side, possibly in preparation for the upcoming Anna Karenina, Knightley is initially off-putting in a slightly overplayed version of her malady, threatening to dislocate her jaw with every jarring take. Yet she too finds her voice in this tale, that as we later learn has a tragic ending at the start of Holocaust and the Second World War. Also worth singling out is Vincent Cassel as the hedonist Otto Gross, who was himself an analytical pioneer, for completely playing the yin to Jung’s yang.

If A Dangerous Method had simply been a biopic of the origin of two of histories most famous minds, then Cronenberg’s film wouldn’t have been anything that a first year psych study could have taken you through. Instead, Hampton, Cronenberg and the incredibly capable cast prove that Freud’s contention of their work being forgotten within the century was completely unfounded for good reason. There are times it dwells on the psycho-sexual aspects of the tale, and like Spielrein it begins to get off on the regular spankings, but it was over these points that Jung and Freud ultimately diverged, and it is doubtful now that their story could have been told in any other way.

[stextbox id=”custom”]Cronenberg takes a familiar story and together with his excellent cast, he makes something brand spanking new. [/stextbox]

A Dangerous Method is released in Australia on 29 March 2012 from Paramount/Transmission.