Welcome back to 80s Bits, the weekly column in which we explore the best and worst of the Decade of Shame. With guest writers, hidden gems and more, it’s truly, truly, truly outrageous.

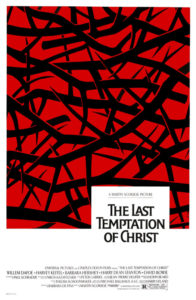

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Martin Scorsese

Writers(s): Paul Schrader

Runtime: 164 minutes

Starring: Willem Dafoe, Harvey Keitel, Barbara Hershey, Harry Dean Stanton, David Bowie

Distributor: Universal

Rating: Certified Bitstastic (?)

[/stextbox]

In an introduction to the 2000 Criterion DVD edition of The Last Temptation of Christ, film critic David Ehrenstein pondered whether we can finally look at the film outside of the controversy it caused on its original release. Over a decade later, the movie is stilled banned in the Philippines and Singapore, a sign that the provocative nature of this Martin Scorsese masterpiece still holds sway around the world. By 1987, Scorsese had been working with a passion for 15 years to get the adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ 1953 novel off the ground, but the studio much preferred him working on the easier sell of The Color of Money (1987) with Tom Crise. After Scorsese transferred to powerhouse agent Michael Ovitz, he abandoned material he had shot in 1983 and set about the film with gusto.

Jesus of Nazareth (Willem Dafoe) is a carpenter who makes crosses for the Romans, a collaboration that torments him and causes him scorn from the other Jewish citizens in the area. Jesus is also tortured by what he describes as “claws” that “slip underneath the skin and tear their way up”, a constant voice in his head which he knows is god speaking directly to him. After Judas Iscariot (Harvey Keitel), initially sent to kill Jesus for collaboration, begins to believe that Jesus is in fact the messiah, he begins to follow Jesus as he builds a following. After helping save the life of prostitue Mary Magdelene (Barbara Hershey), meeting John the Baptist (Andre Gregory) and performing a series of miracles, Jesus knows that he is on a path that will see him sacrifice his life, the only thing he has to give, to save his fellow man.

In the excellent volume Scorsese on Scorsese, the director speaks at length about the writing process and his own relationship with his intense Catholic faith. In an opening monologue to the film, Jesus ponders “God loves me. I know he loves me. I want him to stop”, perhaps taken straight from Kazantzakis’ novel and writer Paul Schrader’s screenplay, but it also speaks to uncredited screenwriter Scorsese’s own struggles with his faith over the years. As Jesus wrenches in the film between being the son of god and the son of man, so too does Scorsese recognise his conflict between being the product of Catholicism and an artist in an industry that often has little time for divinity. This might be exactly why the portrayal of Jesus is the most honest and the most human of all the depictions, especially when compared to what Scorsese calls the “pin up” Jeffrey Hunter in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961).

The Last Temptation of Christ has more in common with Scorsese’s films set on the mean streets of New York than his later historical epics, and not just because of the presence of Harvey Keitel as Judas and David Bowie as Pontius Pilate. Indeed, this casting was part of a process in which Scorsese actively sought to avoid the clichés of the biblical epic. The sermons on the mount, for example, are more of a confrontational conversation that a lecture, more historically accurate than the thousands of assembled meek in the epics of the 1960s. Yet what remains most controversial, and is still the case after almost a quarter of a century, is that Jesus is ultimately depicted as a man seemingly frightened by the growing awareness of his divinity. The film climaxes in an alternate reality depicting Jesus living life as a man briefly, married to Mary Magdelene with children of his own. Staunch Christians see this as a insult, but it doesn’t necessarily contradict what is in the gospels. Having been tempted with a mortal life, Jesus still accepts his destiny to return to the cross and die for the sins of man.

While it may not have been Scorsese’s most successful film either critically or commercially, it remains a legacy and one of the few intelligent discussions on the nature of Jesus in cinema. Unlike Mel Gibson’s later film The Passion of the Christ (2004), where extreme violence and a strict adherence to the morality of the passion play often obscures its message, The Last Temptation of Christ doesn’t provide any easy answers. It poses questions, presenting ideas that are not designed to challenge or undermine faith, but reinforce it in those that have it, and provide a provocative alternative for those who do not.