Welcome back to 80s Bits, the weekly column in which we explore the best and worst of the Decade of Shame. With guest writers, hidden gems and more, it’s truly, truly, truly outrageous. We’ve had a little break, but we haven’t forgotten our favourite decade.

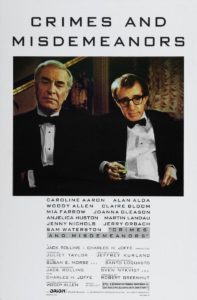

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Woody Allen

Writers(s): Woody Allen

Runtime: 104 minutes

Starring: Alan Alda, Woody Allen, Mia Farrow, Joanna Gleason, Angelica Huston, Martin Landau, Jerry Orbach

Distributor: Orion Pictures

Country: US

Rating: Certified Bitstastic (?)

[/stextbox]

If there is one consistency in the career of Woody Allen, it is his continuing ability to try new things, and the 1980s were arguably filled with his strongest films. His “early, funny films” (to borrow a line from 1980’s Stardust Memories) were influenced heavily by his stand-up comedy and his absurd, morbid and frequently neurotic outlook on life. With a string of zany comedies behind him, including the political farce Bananas (1971) and sci-fi spoof Sleeper (1973), Allen himself has described Annie Hall (1977) as a “turning point” in his career. [1] From this point forward Allen was no longer expected to produce simply whimsical comedies, but the disappointing reception of Stardust Memories (1980), after the Academy Award winning Manhattan (1979), saw him take refuge once again in films such as A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1983).

However, throughout the 1980s, Allen entered an experimental period, crafting a filmography unlike any other. Beginning with the mockumentary Zelig (1983), Allen released the almost flawless triple treat of Broadway Danny Rose (1984), The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) and Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), the nostalgic Radio Days (1987), the Bergman-inspired Another Woman (1988) and September (1987) followed. By the time he reached the end of the 1980s, Allen had rediscovered his own voice.

In Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), we follow the twin and occasionally intertwined stories of filmmaker Clifford Stern (Woody Allen) and ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau). Judah is a family man with a successful career, threatened with derailment when flight attendant Dolores (Angelica Huston) threatens to go public with their affair. He takes the advice of his Rabbi and that of his murderous brother (Jerry Orbach), and the path he chooses leads to inexorable guilt. Meanwhile, Clifford is hired by his arrogant brother-in-law Lester (Alan Alda) to film a documentary about Lester’s life and work, but finds himself falling for Lester’s associate producer, Halley Reed (Mia Farrow).

With this film, Allen revisits some of the themes he explored almost fifteen years earlier in Love and Death. While that film, in keeping with the style of films he was making at the time, ostensibly parodied the great Russian epics and their grandeur, here he returns more to the central idea of literature and its conversation with film. The concept of a character who has killed somebody and yet goes about living their daily life is a direct dialogue with Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, just as Allen did decades later in Match Point (2006). Indeed, Crimes and Misdemeanors is also what Florence Colombani [2] describes as a “polyphonic film” with Match Point.

Yet with this film, he tempers the more serious elements with Allen and Farrow’s lighter story, although this too ends in disappointment for Cliff. One of Allen’s more nihilistic films, perhaps Allen is simply stating here what he has inferred in all of this work. Were it not for some studio insistence that Allen write a small part for himself, we would have missed out on some of the most memorable Woodyisms of his career, especially “The last time I was inside a woman was when I visited the Statue of Liberty.” Allen’s presence also prevents the film from simply being another bleak study of human nature, maybe unconsciously acknowledging the strength of his own persona on the films.

References:

- Stig Bjorkman (ed.) Woody Allen on Woody Allen. London: Faber and Faber, 1993, Revised Edition 2004, p. 75-93.

- Florence Colombani, Masters of Cinema: Woody Allen. Paris: Cahiers du Cinema, 2010, Revised English Edition, p. 92

- Roger Ebert, “2046”. Chicago Sun-Times. Source: Link