The inspiring and magical debut feature dealing with hope in the face of tragedy is difficult to classify, but impossible to forget.

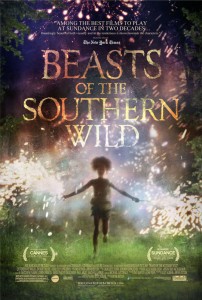

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Benh Zeitlin

Writers: Lucy Alibar, Benh Zeitlin

Runtime: 92 minutes

Starring: Quvenzhané Wallis, Dwight Henry

Festival: Sydney Film Festival 2012

Distributor: Icon (Australia), Fox Searchlight (US)

Country: US

Rating (?): Certified Bitstastic

[/stextbox]

The devastation following Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans and its surrounds still resonantes to this day. The natural disaster did not so much create an impoverished nation, but rather it revealed one already living in the southern Delta. Spike Lee’s documentary When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2009) argued that many of the problems were preventable ones, while HBO’s Tremé is a serial drama focusing on the lives of a New Orleans neighbourhood getting on with life in the wake of tragedy. Debut director Benh Zeitlin mixes the fantasy world of a child with fact to demonstrate the spirit of a people before and after a tragedy.

In this form of a fairy tale, Zeitlin echoes Terrence Malick’s eye for nature in his lingering study of the green and brown wetness of a sticky bayou community called The Bathtub. Sitting outside the levees of an unnamed Louisiana city, it might well be New Orleans but this rapidly becomes irrelevant. Rich and full of life, The Bathtub is also hauntingly sad, filled with a group of proud tragics who define themselves by their differences to what they see as the land-based “others”. We glimpse this world through the eyes of Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis), a young girl who lives in a ramshackle house near her alcoholic father Wink (Dwight Henry). When disaster strikes, the community rallies together with a sense of hope belying the inevitability of their fate.

It is difficult to traditionally describe the naturalism of the principal players in Beasts of the Southern Wild. This is perhaps because non-professional performers Wallis and Henry are not so much acting as extending themselves into a world that sits on the border of cinema and reality. It is a rarity that a child’s voice is so accurately rendered in film, rather than a precocious child filtering words an adult has put into their mouths. With Zeitlin’s script, co-written with Lucy Alibar, there is a magical quality to watching these people on-screen. Hushpuppy is told that her mother simply “swam away”, leaving her with her sometimes absent father, who is just as likely to be off fishing as he is outright striking her. His fatherhood is one of tough love, preparing her for the adversities ahead.

Beasts of the Southern Wild is a stylistic continuance of Zeitlin’s 2006 short Glory at Sea, which similarly leaves much to the interpretation of the viewer. A mixture of fantasy elements, including CGI boar-like creatures called aurochs that may not actually be there, naturalistic acting and a simultaneous glorification and sinister portrayal of nature seamlessly merge into a singular wonderful whole. Zeitlin has captured the post-apocalyptic nightmare of John Hillcoat’s The Road, another tale viewed through the eyes of a child, and fused it with the surrealist fantasy of Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are (2009). The result is a wholly unique voice, and an ambitious accomplishment for an independent production.

Few debut films manage to be saddled with the term “masterpiece” on their first pass, and this singular take on the coming of age story gets almost everything right from the start. While the fatality of the narrative perhaps may heavily direct the last third of the film, Beasts of the Southern Wild is a film that sets up its punches and ensures that you feel them. The most human of all possible stories is a startlingly original film that will remain a classic for years to come.

Beasts of the Southern Wild played at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2012. It is released in the US on 27 June 2012 from Fox Searchlight Pictures, and in Australia from 13 September 2012 from Icon.