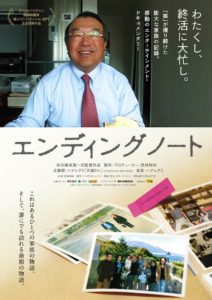

A reflection on a former Japanese salaryman’s final days brings us a joyous and intimate celebration of life.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Ending Note: Death of a Japanese Salesman (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Mami Sunada

Runtime: 90 minutes

Starring: Tomoaki Sunada

Festival: Sydney Film Festival 2012

Distributor: TBA

Country: Japan

Rating (?): Highly Recommended

[/stextbox]

An inevitable part of living is dealing with death, and is a fate that awaits us all regardless of where we live or how much money we earn. When former marketing man Tomoaki Sunada learns of his inoperable cancer shortly after retiring, he takes the same pragmatic approach to his imminent demise as he has with all other things in life. A common practice in Japan, he begins a ‘end of life’ diary, or an “ending note”, detailing all of the things he would like to do before he goes. In addition to planning his own funeral, and being baptised so he can have a ‘simple’ Christian ceremony at a local church, his list is a simple one of playing with his grandchildren and saying “I love you” to his wife. Through the lens of his youngest daughter Mami Sunada, we learn how important those things are to Tomoaki’s life.

Funerary rites and the conversation around death is a delicate and complex one in Japan, coming with taboos and rituals that will often be impenetrable to outsiders. A handful of Japanese films have dealt with funeral preparation, including the early 1980s Jûzô Itami comedy The Funeral (1984) and Yôjirô Takita’s Oscar winning Departures (2009). Rarely have we been given such an intimate portrait into the restrained emotional balance that surrounds a Japanese death, or into the private lives of a family suffering personal tragedy. The process of making a video diary before death has apparently become increasingly popular in Japan, but his daughter becomes the ever-present observer in Tomoaki’s late life, capturing moments that Tomoaki may not have shared on his own.

Shot over the period of time covering Tomoaki’s discovery of the cancer to his death, we learn of Tomoaki’s shift in perspective from workaholic to family man in his later life. The title might recall Arthur Miller’s famous play, but its original Japanese title of Ending Note (エンディングノート) demonstrates that the focus is more on what can be achieved in the short time he has left, rather than simply reflecting on a life unfulfilled. The structure is mostly linear, although cutaways to his retirement and the early days of his cancer show how much he deteriorated in a short period of time. Mami Sunada has also provided the voice over on behalf of her father, which helps maintain some distance from the subject, but also acts as a constant inner monologue for the ailing subject.

Despite the reported box office success and awards the film has received, and a production credit from the always wonderful Hirokazu Kore-eda, Ending Note: Death of a Japanese Salesman is very personal film for both Sunadas. Capturing wonderfully candid moments with a local priest, Tomoaki’s attention to detail and a disarmingly insightful set of grandchildren, we get a sense of the love Tomoaki’s family has for him. While he is willing to dimiss himself a workaholic, and certainly elements of that remain, his family rallies around him from around the world, theirs lives all the better for having him in them. Sunada’s film brings us close to being a part of her family, and as he makes his final farewells to his family, there won’t be a dry eye in the house.

Death of a Japanese Salesman played at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2012.