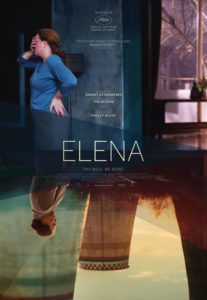

Andrei Zvyagintsev’s third film is visually striking, but also slow-moving and far too familiar in its literary leanings.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Elena (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Andrei Zvyagintsev

Writer(s): Oleg Negin

Runtime: 109 minutes

Starring: Nadezhda Markina, Andrey Smirnov, Elena Lyadova, Alexey Rozin

Distributor: Palace Films

Country: Russia

Rating (?): Wait for DVD/Blu-ray (★★½)

[/stextbox]

In this glacially-paced soap opera, Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsev wears his influences on his sleeve as clearly as his sense of social disorder. Following his debut film The Return (2003), for which he won Venice’s Golden Lion, Zvyagintsev was hailed as a Russian voice to watch. However, his follow-up The Banishment (2007) received fewer accolades, and for many Elena will be a return to form. Winner of the Un Certain Regard Special Jury Prize at Cannes last year, it is an often visually striking and measured character piece, largely focusing on a single woman. However, it also has a far too familiar ‘crime and punishment’ motif that has been done so often before, which is perhaps why Zvyagintsev takes so many narrative shortcuts in getting there.

The middle-aged Elena (Nadezhda Markina) and her husband Vladimir (Andrey Smirnov) are from opposite ends of the social spectrum. Having met later in life, Elena is a former nurse whose son Sergei (Alexey Rozin), from a previous marriage, struggles to make ends meet. Meanwhile, Vladmir’s estranged daughter Katya (Elena Lyadova) has always been a rebel, rarely speaking with her father. When Sergei’s son needs extra money to secure a university place and dodge the draft, Vladimir refuses. However, when Vladimir suffers a heart attack, and an unexpected reconciliation takes place, Elena’s inheritance is threatened and she must decide what is best for her own family.

Elena aims for noir but lands on gris, perhaps even beige, stretching its short film melodrama out over feature lengths. Zvyagintsev is unquestionably skilled at creating a sense of foreboding, opening his film with a lingering shot of crows perched outside Vladimir and Elena’s pristine apartment. Coupled with Phillip Glass’ often overwhelmingly dramatic score, and other totems that include a dead horse, there’s a sense that there will not be a positive ending for the inhabitants of that apartment. Far less subtle is the nuclear power plant that Sergei’s family lives in the shadows of, a symbol of the inevitability of their fate and the disparity between rich and poor. Capitalism, for all of its perks for those with money, is not the democratisation some may have hoped for after the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

Given the elongated exposition, Elena’s critical life-changing decision is made in a heartbeat, almost negating anything that has come before. What remains is a shell of Dostoyevsky, a person left dealing with the proceeds of a serious crime and waiting for the inevitable punishment. Woody Allen explored this kind of intertextual conversation with literature in Crimes and Misdemeanors (1986) and again later in Match Point (2005), but in Elena it only ever engages with Crime and Punishment on the surface level. Bookended with the same elongated shot that opened the film, we are left wondering if what we have witnessed counts for anything.

Elena is released in Australia on 21 June 2012 from Palace Films.

Comments

1 response to “Review: Elena”

Prince of Swine is the controversial film now on DVD/VOD. A new girl in town puts Hollywood on trial. http://www.princeofswine.com/store.html