A thorough and emotional examination of a novel solution to an epidemic problem, albeit one that often labours its point via voyeuristic methods.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Interrupters (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

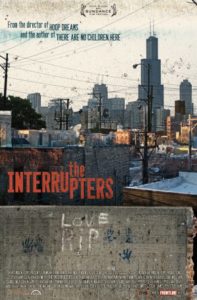

Director: Steve James

Runtime: 125 minutes

Starring: Eddie Bocanegra, Tio Hardiman, Ameena Matthews, Gary Slutkin, Ricardo “Cobe” Williams

Festival: Revelation Film Festival

Distributor: TBA

Country: US

Rating (?): Worth A Look (★★★)

[/stextbox]

Chicago’s CeaseFire Model was launched in 2000 in one of the most violent communities in Chicago at the time, and one indicative of the culture of violence that spreads across the United States of America. In 2004, Illinois CeaseFire director Tio Hardiman introduced the Violence Interrupter model, whereby a small group of people actively try to step in and stop the cycle of retribution and violence that causes a seemingly endless pall of death that hangs over communities like the troubled Chicago South Side suburb of Englewood.

Hoop Dreams director Steve James takes producer Alex Kotlowitz’s 2009 New York Times article as his inspiration, and takes his cameras into the so-called “Black Belt” of Chicago. The predominantly African-American area is renowned for its low rates of education and high degree of unemployment, a combination of factors that lead to many of the citizens turning to gang-related activities, or being caught in the violence that results from the culture it engenders. The film follows three interrupters – Ameena Matthews, Cobe Williams and Eddie Bocanegra. Ameena, the daughter of a major gang leader in the 1970s, is a former teen member of that world and now spends time trying to stop kids from doing the same. Cobe and Eddie have both done long stretches in prison for serious violent and drug-related crimes.

The Interrupters is undoubtedly an important discussion, and the work that it follows is essential to the healing of the communities it penetrates. Ameena in particular is an inspirational figure, swinging easily between being a prophet of peace and speaking the language of her former life. Her dedication is admirable, particularly in the light of her father being the founder of the Black P Stones, who along with The Gangster Disciples are responsible for most of the drug activity in the area. In many ways she, and her colleagues, are perfect examples of what the film represents: a tough honesty that isn’t always pretty, but inspires the change that it wants to be.

Yet the film makes its point very quickly, and much of the remainder is spend hammering home that message through examples that often labour the point. There are undoubtedly thousands of cases across America that mirror their stories, but what is remarkable about them all is that none of them are exceptional. For people growing up in the same conditions, this is a way of life.

However, The Interrupters comes dangerously close to losing its message in the sheer weight of information it presents, and the two-hour documentary could have been just as powerful as a television special half that length. In that time, it also never really commits to the negative aspects of what they do, short of a brief interlude in which one of the team is shot. Even then, the bigger implications about intervening in complex communities are never asked. Regardless, this is documentary evidence of an incredible movement that hopefully ignites change in violent communities around the world.

The Interrupters screened at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival in July 2012.