A fable mixed with nostalgic surrealism, Miguel Gomes delivers poetry on film in an homage to cinema that defies conventional storytelling.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Tabu (2012)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Miguel Gomes

Writer(s): Miguel Gomes, Mariana Ricardo

Runtime: 110 minutes

Starring: Ana Moreira, Carloto Cotta, Henrique Espirito Santo, Teresa Madruga, Laura Sovera

Festival: Melbourne International Film Festival 2012

Distributor: Palace Films

Country: Portugal

Rating (?):Highly Recommended (★★★★)

[/stextbox]

Everything old is new again in cinema, with the past just as much a portal to other worlds as the most technologically advanced science fiction. Indeed, it is difficult to not feel at least a little bit of The Artist in Miguel Gomes’s latest feature, sharing a strong sense of nostalgia and retro aesthetic that is clearly in love with the very notion of cinema. Yet Tabu should not be mistaken for a lighthearted romp through the golden era of filmmaking, despite sharing a title with F.W. Murnau’s 1931 Tabu: A Story of the South Seas. Instead, former film critic Gomes weaves a tale out of Africa that is romance wrapped in a fable, dissecting Portuguese colonialism in the process.

Tabu begins in modern-day Lisbon, in a chapter called ‘Paradise Lost’, where the otherwise ordinary Pilar (Teresa Madruga) tries to console her over-the-top and bitter neighbour Aurora (Laura Soveral), who believes that her maid is practicing voodoo on her. When Aurora’s health begins to fail, she summons Gian Luca (Henrique Espírito Santo), who is slowly revealed to be her long-lost lover. The initial and thoroughly modern sequences seem sterile in light of what is to come, so thankfully the film segues into a darkened Africa for the second act simply called ‘Paradise’. In the shadows of the foothills of Mount Tabu, the beautiful young “big-game hunter” Aurora (Ana Moreira) embarks on an affair with the young Gian Luca (played in flashback by Carloto Cotta), altering them both and perhaps even the world around them.

Illuminated in a glorious 16mm vision by cinematographer Rui Poças, and framed in the 4:3 ratio that immediately evokes yesteryear, the second half of Tabu is entirely silent, save for the narration by Santo and a selection of Phil Spector tunes. The landscape in Tabu is one of memory and loss, and the journey through it is a mesmerising one. The non-traditional narrative is aimed at keeping audiences slightly off-balance throughout, perhaps to suggest that we are intruding on the most personal moments of these doomed lovers. Without the aid of dialogue, we are simply left to interpret what conversations they are having through gesture, movement and an assortment of ambiguous sounds that serve as a secondary narrative. One of the closest comparisons would be the soundscape of David Lynch’s Eraserhead, where the internal and external sources of sound are often reversed for the purposes of disorientation.

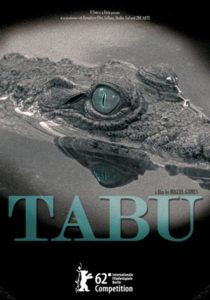

Just like the recurring symbolism of crocodiles, Tabu hints at what lies beneath the surface. While the images themselves might be indicative of the follies of a group of privileged colonials, these images belie the complex web of emotions that can’t be described in something as clumsy as words. Bathed in the unreliable glow of sentimental reminiscence, made more so by the age and bias of the narrator, Gomes wears this emotional misdirection on his sleeve, playing on romantic notions of the dark heart of Africa.

The winner of the FIPRESCI Prize and the Alfred Bauer Award at Berlinale, it is a film that is destined to split audiences straight down the middle, not least of which because the same nostalgic notion of story could also work as an initial hurdle for modern audiences. Yet this also keeps in line with the conscious commentary on the subjective nature of storytelling. Tabu is a film to get swept away by, to live a life vicariously and to soak in at leisure.

Tabu played at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2012 and at the Melbourne International Film Festival in August 2012. It will be distributed in Australia by Palace Films.