Everybody’s got a story, and we all have our favourites and guilty pleasures. From the art-house to the bargain basement, movies impact us all in different ways. Judge not lest ye be judged. Here we hang out our Personal Bits. This week’s guest is ‘Bits regular Paul Grose.

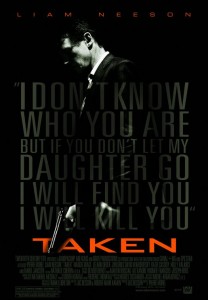

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Taken (2008)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”220″]

Director: Pierre Morel

Writer(s): Luc Besson, Robert Mark Kamen

Runtime: 93 minutes

Starring: Liam Neeson, Maggie Grace, Famke Janssen, Xander Berkeley, Katie Cassidy

Studio: EuropaCorp/Canal+

Country: France

[/stextbox]

Taken is a film directed by Pierre Morel, and derived from a screenplay by the writers of 2001’s The Transporters, Luc Besson, and Robert Mark Kamen. Made in 2008 Taken, is an interesting example of the effect that an actor’s screen persona can have on a film. With Taken several aesthetics come into play that shapes what takes place with the character, and on screen. The film stars Liam Neeson, who now appears to be modelled on a modern day Robert Mitchum.

Liam Neeson portrays divorced father Bryan Mills. A former CIA agent, he is attempting to rebuild a relationship with his daughter Kim (Maggie Grace). We learn that he has given up his career in order to attempt this reconciliation, which has cost him his marriage. Frustratingly Bryan’s attempts at forming a relationship with his daughter are made difficult by his uncooperative ex-wife Lenore (Famke Janssen) and her wealthy new husband Stuart (Xander Berkeley). These two spoil and indulge Kim in all her desires. One such grant is a trip to Paris. Tragedy strikes on this holiday when Kim is kidnaped by an Albanian gang of human traffickers. Bryan, infatuated with his daughter’s safety at all times, swears to Lenore and Stuart that he will rescue his daughter from the kidnappers. Bryan learns that he has a limited time to do this before she disappears forever. With time running out, Bryan delves into the Paris underworld.

Fast-paced and filled with action, Taken is built around the Neeson persona. Liam Neeson first came to prominence by playing strong supporting character roles. He was Churchill, the doomed sailor to Mel Gibson’s’ Mr Christian in 1984’s The Bounty, and Sir Gawain in 1981’s Excalibur. Look carefully and you will also see him in 1986’s The Mission, and 1987’s A Prayer for The Dying. When Taken arrived, Liam Neeson had built himself a solid career out of lead and supporting roles. Ironically his supporting role work still forms a large part of his cannon and produces some of his most successful roles such as Qui-Gon Jinn in 1999’s The Phantom Menace, and Ducard in 2005’s Batman Begins. Yet Taken is his film and its narrative swiftly moves forward around set pieces including chases and fight scenes. The fight sequences are very interesting, and the reason for this is as a direct result of Neeson himself.

In Taken, Nesson incorporates his body frame and build to be used in the films narrative. A tall man at 6 ft. 4, and weighing 195 pounds, director Morel inserts Nessons character into positions and situations where his body frame plays a vital role. A lot of the fight scenes take place in small confined areas. Mills is seen climbing along thin ledges with dangerous drops, and crawling into confined spaces. While in several chase set pieces it is obvious that, because of his build, Mills has a problem running. He is repeatedly seen to struggle as he pursues his prey on foot. Cleverly though, in opposition to these restrictions, some of the greatest tension is produced when Mills enters a room, usually a small space where he fills the room with apprehension. Two fine examples of this change of the environment are the confrontation with Victor in the sales booth, and with Marko in the apartment kitchen.

Still working in conjunction with the Neeson persona, the dialogue is also used to great effect within the film. Again, this is structured to fit with the audience’s identification with the actor rather than the character. Neeson is slowly becoming as synonymous with his movie quotes as much as Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Taken has his most famous dialogue to date. Used for the promotion of the film the line “If you let her go now, that will be the end of it. If you don’t let my daughter go… I will find you, and I will kill you” has become a staple of popular culture. This tradition continues today with other great quotes coming from his latest film The Grey (2011).

If you have not seen it, Taken is certainly a guilty pleasure, but it is also controversial, and this has in the past been identified as a result of director Morel. Previously critics and several sources have identified Morel as a root of a racist agenda in his portrayal of stereotyping of Eastern Europeans. There is no doubt about this in Taken, as the Albanians are in no way portrayed in a pleasant light, and are identified in the film as at being at the centre of the human trafficking of individuals in Paris. Yet one of the primary villains of the piece is Saint Clair – an English man. So that aspect is open to debate, and as I have not seen any of his other films am not in a position to comment.

With a sequel set for release in the near future, Taken shows how outside aesthetics influence what we seen on the screen. In this case, it’s an actor’s screen persona and its relationship with the film going public, and also a director’s conscious decisions to insert both physical and mental agendas into a finished product. It is interesting to read these aspects into Taken, and adds a further layer to a great viewing experience.

Got your own Personal Bits? If you want to write about your favourite film, please let us know! We will feature a new one every week!