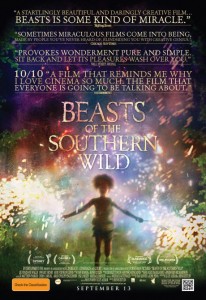

Few debut films manage to be saddled with the term “masterpiece” on their first pass, but the award-winning Beasts of the Southern Wild breaks the mould. Winner of the Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic at its 2012 Sundance Film Festival debut, it has gone on to win the Caméra d’Or award at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, the first of what will undoubtedly be countless accolades. We were lucky enough to chat with director Benh Zeitlin on his visit to Australia for the Melbourne International Film Festival.

Few debut films manage to be saddled with the term “masterpiece” on their first pass, but the award-winning Beasts of the Southern Wild breaks the mould. Winner of the Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic at its 2012 Sundance Film Festival debut, it has gone on to win the Caméra d’Or award at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, the first of what will undoubtedly be countless accolades. We were lucky enough to chat with director Benh Zeitlin on his visit to Australia for the Melbourne International Film Festival.

In this form of a fairy tale, Zeitlin echoes Terrence Malick’s eye for nature in his lingering study of the green and brown wetness of a sticky bayou community called The Bathtub. Sitting outside the levees of an unnamed Louisiana city, it might well be New Orleans but this rapidly becomes irrelevant. We glimpse this world through the eyes of Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis), a young girl who lives in a ramshackle house near her alcoholic father Wink (Dwight Henry). When disaster strikes, the community rallies together with a sense of hope belying the inevitability of their fate.

We need to thank Icon Film Distribution Australia for allowing us time with the filmmaker, and of course, Mr. Zeitlin for his generous time and answers. Beasts of the Southern Wild is released in Australia on 13 September 2012 from Icon.

To start off with, congratulations on the film. It’s such a beautiful film and I sincerely don’t think I’ve been moved so much by a film in recent memory.

Thank you.

I guess that’s something that a lot of people have been saying. There’s been this overwhelming response to it. Now that the film is out in the public eye, I believe it just came out in the States…

Yeah, about six weeks ago.

Did you ever envisage this kind of response to it at all?

No, definitely not. You don’t even think about it. You think a lot about audiences, and wanting to communicate with people, and wanting to make sure the film works, you know? Showing it to lots of people before we put it out, but I never even thought for a second past the moment of getting the film done while I was making it. You know, we finished the film two days before Sundance and there was no real time to sit around, twiddle our thumbs and imagine whether people were going to like it or not, or what would happen. It was all very foreign to me. But I’m learning about it as I go. Basically, I didn’t know any of this existed. [Laughs]

The film itself discusses a lot of real, and very recent, world events. There’s obvious parallels there. It does it through a fantasy perspective, and certainly that of a child. Did that connection between loss and place come from Lucy Alibar’s play or was it something you came to later?

The play and movie are very different. It was more like an inspiration than an adaptation in some ways. I do think that one thing that came from the play – the play wasn’t about Louisiana or current events, it had nothing to do with storms or water or anything like that. It really focused around this little girl whose father was sick, and as the father got sicker, nature itself started to come apart and the end of the world started to happen. The apocalypse was in sync with the father, from the little kid’s perspective. That sort of sense that idea of connecting a tangible event to a more fantastical epic, fable event was something that came from the play.

Many people are still dealing with the aftermath of Katrina, an event very much in living memory. Was that approach of combining those concepts the logical way for you to deal with that kind of tragedy?

You know, the film wasn’t specifically attached to Katrina as much as it is, especially south Louisiana, south of New Orleans. Katrina was sort of a very urban phenomenon, and south of there was much more effected by storms that happened two years later, Gustav and Ike. The film was really trying to take all the things, all the factors that are going into the collapse of South Louisiana as an environment and express them in a way that wasn’t documentary, that wasn’t actually getting into the actual tangible events that happened. It just wasn’t our interest. We wanted to tell the emotional side of the story and not the social issue, or the current events or the documentaries. There’s lots of great documentaries, and we were trying to get into what does it feel like to lose a place, and what does it feel like to be living on land that’s disappearing. That was really our focus. To get at that, we really needed to take a step away from reality and think about the story more as a fable.

And when you started thinking about the story as a fable, were there particular stories you looked at that were parallels?

There wasn’t a specific story on this one, which I’ve done in the past a lot. I made a short film that sort of jumped off the Orpheus myth [Glory at Sea]. This one just had more of a sense, because the events of the story aren’t actually fable-like or epic, but the actual tangible things that happen are quite realistic. It’s more coming from the perspective of a girl who think of her world as a story, and is creating a narrative between herself and the cavemen, and herself and these extinct animals. Understanding her own world in this epic context. So we always tried to think ‘What is the tale that Hushpuppy is writing about herself?’ as opposed to kind of adapting a different story in the broader sense.

I was at Sundance London earlier in the year, and one of the things that a lot of the filmmakers there spoke about was the importance of the Sundance Labs in crafting their story. Could you talk a bit about how much the Labs changed the story, and how much it developed in that period?

It was massively. We showed up at Sundance with a really raw first draft that I’d written in the two weeks preceding submitting it. So it was really like a burst of ideas when we went there, and the Labs are great because they really discipline you and force you to examine choices, and examine why it is you set out to make the story in the first place. A lot of times, ideas just come to you and images and lines. It’s really a disorganised grab-bag of thoughts, and Sundance really helps you examine where those thoughts come from, and what it is you’re trying to say with them. It really helped us come up with a structure around which to make choices. The film, just from that early point, because a lot more focused and I think we started to understand what it meant and how to tell this story which was really and emotional story rather than a narrative story.

And how much of that changed again once you had your leads in place?

A lot. You know, we sort of start with this kind of fable, and there’s all this realism that comes into it. We set up a system in which these tangible things are actually on-screen can effect that story. Just every line in the film, I would ask the actors, ‘How would you say this?’. Put this in your own words, and all that language got rewritten. Even actions characters take and scenes in the film come from interviews I had with the actors and their experiences, and their lives become very much part of the story. Not that anybody is playing themselves, but we really tried to cast people whose experiences are reflected in the story we’re trying to tell. It gives us a tremendous amount of material that I could have never thought up just comes from the actors.

Was there always the intention to cast non-professionals, and from the area, or did that also come out in development?

It was always supposed to be a combination of non-professionals from the area and professional actors, and that isn’t what ended up happening. We ended up casting all non-professionals. You know, it was sort of surprising that’s how it ended up working. It just had a lot to do with our casting process, where we’re really looking for a lot more than acting ability, or what somebody looked like, kind of fitting into the script that’s been written. A lot of times, we were finding people and meeting people that we found to be extraordinary and who also had this ability to perform, and then also have these amazing lives that we can draw from to incorporate into the story. So we really tried to create a process in which we were able to adapt people coming into the story, and able to create an environment where even if you don’t have the acting training, there’s a way to work within the way we make the film. It’s all very much part of the process that we tried to create.

This is something that has been touched on in countless interviews I’ve read with you. The fact that over 3500 kids were looked at for the lead role of Hushpuppy. Was there a particular quality that stood out in Quvenzhané, and did I pronounce that correctly?

[Laughs] Almost. Kwa-ven-jen-ay. There was a lot of different things. It was just how advanced she is for her age, and how she just had a self-reflection that most people that age don’t have. Or she really was able to understand how to go into character and how to learn lines and how to focus. Also, she had a very ferocious sense of self, where it wasn’t that I could tell her to do anything. She was ‘No, I think it would happen like this’. Or ‘No, I won’t do that. I’m morally opposed’. [Laugh] I would ask her to throw something at someone, and she would say ‘No, that’s not right, you’re not supposed to do that’. She had a very strong sense of herself, and that is what we wanted. We didn’t want a puppet. Someone who was really going to take a hold of the character, the way an actor would, and she really brought all those qualities.

You touched on your shorts before, and Glory at Sea seems to be a stylistic forebear in some ways to Beasts. Did you consciously look at other cinema influences going into Beasts?

We did some, they were very all over the place. We looked at a lot of documentary photography for the cinematography, the Les Blanks docs from the ’70s. There was also this Australian short film that was a big influence on the cinematography called Jerrycan. Narratively, we looked at a lot of children’s films, the structures of Disney stories. The sort of things that a kid would have in their head, try to figure out how Hushpuppy would understand things. Just a lot of things like [Emir] Kusturica’s films, and Bob Fosse’s films, and Milos Forman and [Federico] Fellini that has this come of vibrance that extended past the serene in some ways. We looked at a lot of films like that. So lots of different things for different elements of the movie we looked at and studied.

So many productions have gone through Louisiana in the last couple of years, so what was the reception like that you got from the locals?

We were in a very different part of Louisiana from where films get shot. There’s a big studio up north and out west that most of the films go to that are in the city, and this was a totally different region. So certainly I was the only person with New York licence plates driving down the road. It was a very warm, you know – once people got used to the idea of me, and realised they could make fun of me all they wanted, it became a lot of fun to be the outsider in this very remote place. It’s incredibly hospitable. We were living in people’s houses, and their campers, and were really taken in by the community. We never would have survived the film if we hadn’t. We all would have very quickly sunk into the swamp and been bit by rattlesnakes and never made it out of there. So they really protected us and collaborated with us and guided us through the film.

The last thing I need to ask, and certainly after this very long tour that you’ve been on with the film, what plans do you have for your next picture, or do you still have your mind in the publicity for this?

Well, I’m trying to find time to write the next thing, but it’s going to be another big folktale. I’m hoping to shoot it in Louisiana, and we’re really trying to keep the same team in tact. Just really trying to continue this method of making films and not let that change but hopefully having more resources will allow us to do even better and just keep on improving.