A frank discussion of bullying in schools, and what people can do about it, has a very optimistic view of the future.

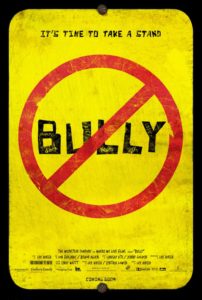

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Bully (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Lee Hirsch

Writer: Cynthia Lowen

Runtime: 90 minutes

Starring: Alex Libby, Kelby Johnson, Ja’Meya Jackson

Distributor: Roadshow Films

Country: US

Rating (?): Worth A Look (★★★)

Debuting at the Tribeca Film Festival last year, Bully follows group of families across the US as they deal with the tragedies and consequences of bullying at school. The film has become part of a national, and indeed international campaign, called The Bully Project, and aims to be a self-sustaining movement to aid the voiceless in the fight against bullying in all walks of life. Prior to this, director Lee Hirsch was best known for his award-winning documentary Amandla!: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony, which examined the struggles of black South Africans against Apartheid through music. As a self-confessed victim of bullying, Hirsch explores the effects of bullying on a group of students and their parents, along with some of the progress that has been made towards stamping it out.

During the 2009-2010 school year, the documentary follows five sets of students and their families from high schools in Georgia, Iowa, Texas, Mississippi and Oklahoma. There’s Alex Libby, the central figure in the film in many ways, who tells us his bullies “punch me in the jaw, strangle me, take things out of my hand”. Kelby Johnson, and openly gay student in a small-minded town, who was picked on not only by other students but by the institution as well. Meanwhile, Ja’Meya Jackson was a nationally infamous case of a young girl who snapped after constant bullying and pulled a gun on a bus full of her fellow students, only to spend months in a Juvenile Delinquent Center. Also present are the parents of Tyler Long and Ty Smalley, victims of bullying who took their own lives as a result of that intimidation.

It will come as little surprise to many that bullying is commonplace in America’s schools. Indeed, bullying is present in all walks of life, from the schoolyard to the workplace, but Bully‘s major focus is on the school system of principally bible belt states in the US. What Hirsch’s documentary offers us for the first time is a fly-on-the-wall account of what life is actually like for some of these kids, and also for the families who are living with the effects of bullying several years down the track. Watching some of the actions of these kids towards other kids is often chilling, and the alternative indifference and helplessness of the school authorities is worrying.

As noble as the intentions are of Bully, one can’t help but wondering if the presence of Hirsch and his cameras exacerbated some of the behaviour of kids in this film. While decoy kids were used for the central subjects, in the case of Alex and Kelby, both kids ultimately wound up at different schools before things began to improve for them. The real emotional impact comes with the families of Tyler Long and Ty Smalley, who have suffered losses that no parent should have to as the result of institutionalised bullying. It is their campaigns to see the eradication of this behaviour in schools that forms much of the second half of the film.

It may be overly optimistic to believe that a handful of students holding candlelight vigils will eradicate behaviour patterns that have been around as long as the notion of ‘survival of the fittest’. Yet it is a step in the right direction. What Bully does first and foremost is raise awareness of the issue, and keep it in the public eye. On that level, the film is a success and something for which the filmmakers should be commended.

Bully was released in Australia on 23 August 2012 from Roadshow Films.