We caught up with P.J Hogan about halfway through his press junket, where he conceded that he’s been “going mental with Mental” on the road. The Brisbane-born filmmaker had his first big hit in 1994 with Muriel’s Wedding, an iconic Australian film that also made a star out of Toni Collette. In the interim, Hogan has been busy in the US with My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997), a big-budget Peter Pan (2003) and Confessions of a Shopaholic (2009). With Mental, Hogan reunites with Collette for the first time to convey a tale that is mostly autobiographical.

We caught up with P.J Hogan about halfway through his press junket, where he conceded that he’s been “going mental with Mental” on the road. The Brisbane-born filmmaker had his first big hit in 1994 with Muriel’s Wedding, an iconic Australian film that also made a star out of Toni Collette. In the interim, Hogan has been busy in the US with My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997), a big-budget Peter Pan (2003) and Confessions of a Shopaholic (2009). With Mental, Hogan reunites with Collette for the first time to convey a tale that is mostly autobiographical.

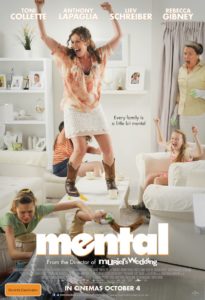

Mental, in Australian cinemas on 4 October 2012, follows the lives of five out of control children emotionally rescued by the outrageous Shaz (Collette) when their mother Shirley (Rebecca Gibney) has a mental breakdown. Their unavailable father Barry (Anthony LaPaglia), a local politician running for reelection, finds Shaz hitchhiking and she changes the lives of the kids. The film, as the title suggests, is suitably mental.

We need to thank the good folks at Universal Pictures Australia for the opportunity, and of course, Mr. Hogan for his time and generous answers.

To start off with, I’ve got to say that as a child, my mother made me watch The Sound of Music countless times…

Then you know.

I know, and I’m starting to suspect that she should have gone to Wollongong.

Well, my mother did go to Wollongong. My mother would always cry at exactly the same time too, the scene I put in the movie. I was very specific about what scene was going to be in the movie. It had to be that scene where Christopher Plummer sings with his children. That was the scene where my mum always cried. They said what scene do you want from The Sound of Music, because you have to be very specific. I know exactly: that scene. When you’re a kid, we had no idea. She would go off like clockwork at that scene. We’d go ‘She’s gone again, shoot us now’. What it was, she wasn’t crying about The Sound of Music, she was crying about the fact that it was a dad bonding with his kids, bonding with his family, and we couldn’t get our dad to come home from the pub. He was a very absent father. Can you be very absent? Yes I think you can.

Yes you can.

He was a very absent, underline, father.

Just short of completely.

[Laughs] Just short of completely. So my mum wanted nothing more than my dad to show up, pull out a guitar and sing Edelweiss, and we’d all cry. But that never happened. He wouldn’t even come back for dinner. So that’s why I put it in the film.

You’ve just alluded to that, that this is a very personal story for you…

Oh yeah. I should stop saying that it’s a story at all. It’s a documentary really.

So why now? What was the impetus?

Well, I’ve known the original Shaz since I was 12 years old. That’s when she came into my life. You know, my mother had a nervous breakdown when I was 12, just vanished, and when we asked our dad where she was he said she was on holiday. That’s the story, and you’re going to stick to it. He was a local politician, up for re-election, so he didn’t want it getting around that his wife had ‘cracked up’, because as he said, nobody votes for a bloke whose wife’s bonkers. So that left him us: five kids that he didn’t get on with, had nothing to say to. To be fair, we were a bunch of ratbags, and I think my dad snapped. He stopped for a hitch-hiker. He picked up this woman from the side of the road, he trusted her because she had a dog, and when we came home from school one day, there she was sitting on the couch. Rolling a cigarette, hunting knife sticking out of her boot – that was the first thing I saw – and she just looked around and said ‘Bit of a mess in here, isn’t it?’. Got us cleaning, sorted us out. That was the original Shaz. To this day, she remains the most inspiring, outrageous and craziest person I’ve ever met.

So I always thought there was a movie about her, about that story, I just didn’t know how to tell it for a very long time. It took a lot of talking out with people I knew, because the original Shaz stayed in my life right up until I was about 30. So there was a lot of rope, story rope. It was which part do you use, which part of the rope do you cut? When I figured out it should be the beginning, how I met her and what she did for us, then it gelled.

There’s a fine line between telling a story about mental illness and comedy…

Actually no. Comedy is always present when you’re dealing with somebody with mental illness. Always. I think people have, and I speak from experience here – my sister has schizophrenia, my brother has bipolar, I’m the father of two autistic children – people just have this image of mentally ill people being depressed all the time. You can’t be depressed all the time, nobody wants to live like that. You’ve got to laugh. Laughter is what helps with the pain. My sister, my schizophrenic sister, one of the things about her when we go out is that she talks really loudly, and people stare at her. She goes ‘Oh, sorry I’m talking so loudly, I’m a bit mental! Bit mental!’ She’s hilarious. So I couldn’t tell the story any other way, because that’s how I’ve experienced life living with my mentally challenged loved ones.

The other thing I can’t imagine is this story being told is anything other than Australia. I think Rebecca Gibney called it “unashamedly Australian”. Could you have told this story in any other place.

No. I guess you mean America, because I’m not going to be making it in France, obviously. The Americans wouldn’t make this. They’d go, ‘Oh no, you can’t do that’. And ‘Can there be an American in it? Can you change it?’ I talked to a few people. As I finished a draft of the screenplay, I showed it to a few friends that I’d worked with. To raise money for it, they said ‘Well, an American will have to play Shaz. Could you set it here too? And that Harold Holt stuff will have to go. We don’t know who he is’. Basically, it destroyed [it]. It would have lost everything. It would have been meaningless. So I knew it was going to have to be a low-budget Australian movie. So that’s what we did. To make it, we all pretty much sacrificed our fees, and I can just tell you that everybody involved in it did it for love.

And is that the difference between making a film in the US and making one here?

I know in the US the films that you’re most passionate about are always the most difficult to make. The ones that you would make for free, you end up making for free. The ones you don’t really care if they get made or not, there’s usually bucketloads of money next to them. I don’t know why that is. It’s just the way the industry works. So I think that any indie film that you see from the USA, that you liked and really worked and had risky material, was probably really difficult to raise money for and to pull off. So when I say difficult to make, I mean difficult to make in the studio system. But it also would have been difficult to make raising money independently, because even the independent world in the USA has got more cautious. Budgets have really been crunched down. Thank goodness for digital now, because at least that’s allowed people to – the audience now accepts things that have got a rawer look, allowing filmmakers to work on a lower budget.

On the flip side, having worked extensively in the US, is there anything the Australian industry could learn from what they’re doing. Is there anything we could try to emulate, I guess?

Look, I’m not sure about that. I’m often asked if we should emulate the Americans, and I just don’t think we should. What are we going to emulate? We can’t blow things up better than they can. We’re never going to make better superhero movies than the Americans. I think that we underestimate the importance of our own cinema. They steal from us all the time. If they’re not steal our actors, or our directors, they’re certainly watching our films. I for one think that if it wasn’t for Dark City you wouldn’t have The Matrix, I can name dozens of others. They see everything, and they’re always on the lookout for new ideas, new people, new talent. What the America film industry be, what would Hollywood be, without just our Australian actors. There’s almost an Australian actor everywhere you look. So I think we should do exactly what we’re doing, I think we should be telling Australian stories. Concentrating on the stories that are meaningful to us, and telling them well. My surprise with Muriel’s Wedding was that it travelled, because I didn’t make it for anybody else but a bunch of Australians. It too was an unabashed, unashamed Australian film, and somehow it connected with people all around the world, not just the USA. I think you make a mistake if you direct looking at America. If you try to do an Australian story, but you really hope its a calling card with the USA. If you don’t connect with your immediate audience, you’re probably not going to connect with that audience either.

Coming back to Australia, was Toni Collette an obvious choice for you, or did the story lend itself to that?

Because I’d met the original Shaz when I was so young, I was talking to Toni about Shaz on the set of Muriel’s Wedding. Toni would say ‘Why are we making a film about this Muriel chick when we should be making a film about Shaz?’ Every time we’d meet, she’d ask ‘How’s that script going?’ Even when it didn’t have a name. I’d say, ‘Slowly, but I’m thinking about it’. I was just trying to find a way into it, so it wouldn’t be Muriel’s Wedding 2. Finally, because the real person was so vivid in my mind, I didn’t hear Toni’s voice, I heard Shaz. But when I read it back, I went ‘Wow, Toni would get this’, because she’s from the western suburbs. She’s a Blacktown girl, you know, she knows those tough broads who’ve been through a lot of shit in their lives and come out stronger and a little broken. She won’t condescend, she won’t do the bogan send-up. Then I got nervous. I really wanted Toni to play the part, but in the interim Toni had become very famous, and could have said no. Luckily for me she didn’t, she committed very quickly.

As you said, you are halfway through this junket now, but do you have an eye on your next project at this point?

I’ve got several projects on the boil at the moment. I don’t know which will come first because they all involve actors whose schedules are very tricky. I used to just concentrate on one thing, I was very obsessive about my projects. I pursued, I refused to do anything but Peter Pan for years. I turned down a lot of things because it was always so close to going, and I ended up waiting years to make that movie. I’ve since decided that my resume is going to be very short if I continue to be that way, so I’ve got three or four things going and I’ll do the one that comes first. I’ve pretty much decided that’s what I’ll do. If I name it, I’m sure it won’t happen. If I go ‘this one’, it will be the other one.

You can follow ‘Shaz’ on Twitter via @shazismental