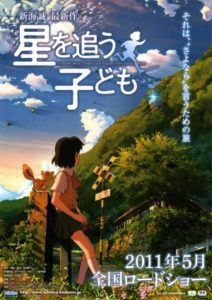

One of the leading voices in modern Japanese animation cracks another winner out of the park with this curious blend of science fiction and musing on the nature of loss.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”Children Who Chase Lost Voices (2011)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Makoto Shinkai

Writers: Makoto Shinkai

Runtime: 116 minutes

Starring: Hisako Kanemoto, Kazuhiko Inoue, Miyu Irino

Distributor: Media Factory, Madman (AU)

Festival: Reel Anime 2012

Country: Japan

Rating (?): Highly Recommended (★★★★)

Like Mamoru Hosada, who also appears at Reel Anime this year with Wolf Children, filmmaker and graphic designer Makoto Shinkai is another person burdened with the heavy label of “The New Hayao Miyazaki”. Shinkai made a splash on the scene with his Voices of a Distant Star (2002), a film he had infamously written, directed and produced on his Power Mac G4. Yet it was with his follow-up 5 Centimeters Per Second that Shinkai sent good vibes around the world, putting aside sci-fi elements for an intimate portrayal of the relationship between two people over a number of years. With his most recent film, Children Who Chase Lost Voices from Deep Below (abbreviated in the West as simply Children Who Chase Lost Voices), the filmmakers retains his emotional viewpoint against an epic backdrop as a young girls sets out on an epic quest to say goodbye.

Pre-teen Asuna (voiced by Hisako Kanemoto) has been forced to deal with the loss of her father, while her mother works long shifts as a nurse and is mostly unavailable. She takes herself off into the hills where she picks up radio signals and intriguing music on a home-made radio using a crystal she discovered. Her fate changes when she encounters the enigmatic Shun (Miyu Irino), who says he is from the faraway land of Agartha, and saves her from an unnaturally large beast that patrols the bridge. He’s wounded in the process, and Asuna learns from her mother that the body of Shun was found in the river. Refusing to believe it is her Shun, she is intrigued by a story her substitute teacher Mr. Morisaki (Kazuhiko Inoue) tells of an underworld, where people can quest to retrieve their loved ones from the land of the dead. Soon Asuna is off on an epic adventure to Agartha, pursued by the militaristic Arch Angels who want to plunder the land for its untapped wealth.

The fascinating thing about Children Who Chase Lost Voices from Deep Below is how it deals with abstract concepts of ‘life’ and ‘death’ and the very notion of saying farewell within the context of a larger story. Shinkai poses a question within this tale, whether it is better to let people and things that have left us go or to forever chase the echo of their voices. Framing this within the traditional motifs of a hero’s journey, Shinkai physically represents the distances between the living and the dead. Leaving us totems along the way, from grotesque creatures that serve as guardians to the world or airships that sail overhead as a representation of heaven, there is a fundamentally pagan approach to the notion of the cycle of living and dying. Rather than simply creating a single monotheistic entity that sits above the Earth, the passages to the afterlife are varied, and they are different for each person. Similarly, it is heavily implied that it is up to the individual to make their own decisions concerning their perception of death, tying the film into the notion that we are all part of a broader consciousness experiencing itself in a subjective fashion.

The visuals in the film are stunning, or more precisely the backdrops are also jaw-drops. With his much bigger group of animations and designers, every frame is filled with an astonishing level of detail that captures the grandeur of the world Shinkai has created. Much of the love has been poured into these vistas, and the characters in the foreground look comparatively simple. Yet this is wholly appropriate, given that the abstractions dwarf any of the characters seen in the film. More of an issue is Shinkai’s struggle in the first act to adequately give the audience a foothold in this new territory, perhaps because he is also forging new ground for himself. This is rapidly forgotten, however, as the film approaches its second half, and Shinkai excels in his comfort zone.

The Japanese animation industry, like any other, has gone through a number of phases over the last decades, but it is comforting to know that there is still room for intimate storytelling within the blockbuster mentality. Indeed, that the two sit so comfortably alongside each other is a testament to Shinkai’s craftsmanship, bringing us a story that could have very easily emerged from Studio Ghibli and leaving his own personal stamp on it.

Wolf Children was released in Japan on 21 July 2011. It screened in Australia in September 2012 as part of Reel Anime.