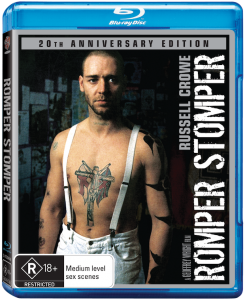

It has been 20 years since the award-winning Australian film Romper Stomper burst onto the Australian scene, amidst controversy and a star-making performance for its lead Russell Crowe. Reel are releasing a 20th anniversary Blu-ray edition of the film, and we were lucky enough to chat with writer/director Geoffrey Wright ahead of its release.

It has been 20 years since the award-winning Australian film Romper Stomper burst onto the Australian scene, amidst controversy and a star-making performance for its lead Russell Crowe. Reel are releasing a 20th anniversary Blu-ray edition of the film, and we were lucky enough to chat with writer/director Geoffrey Wright ahead of its release.

Originally released in 1992, it follows a group of neo-Nazi skinhead youths in Melbourne who have targeted the local Vietnamese community. Led by the charismatic and frightening Hando (Russell Crowe) and his second in command, Davey (the late Daniel Pollock), they meet up with the drug addict Gabrielle (Jacqueline McKenzie) and a love story of sorts begins. As the violence escalates around them, Wright ponders whether or not they can ever get out of this endless cycle.

Throughout the interview, Wright talks about the inception of the film, its controversies, the Australian film industry and finding the right time to re-enter it. We need to thank Roadshow Entertainment/Reel for this opportunity, and of course, Mr. Wright for his generous time and answers.

Romper Stomper is released in Australia on Blu-ray on 3 October 2012 from Reel.

It was a very different time for Australian film then. How difficult was it to get the film made?

Well, I suppose at the time we thought it was difficult, but compared to what would be faced now. They were not so intimidating as what they would be now, because generally speaking it was a less politically correct time in the funding bodies – and in general, anywhere, any aspect of society. I remember someone from Film Victoria saying to me ‘Well, the project scares us a bit, but we’re really obliged to put money into stuff that’s breaking new ground. So we’re going to give you the money’. And I was very grateful. I think there’d be a lot more angst and second guessing if you tried to do it these days.

It was your first feature following short films. I understand it was Dane Sweetman’s story that attracted you at the time. What was it in particular about that inspired you to make the film?

Well, Dane Sweetman was something that we looked at, but it probably didn’t begin with him. It began earlier, we just noticed a shift in some of the street gangs. Some of the street thugs had taken on certain political ideas and drew inspiration from their counterparts in Europe, and we saw it happening here in Melbourne. We thought this was interesting. We started doing a lot of interviews. I’ve still to this day got a box full of 1/4″ tape, of dozens and dozens and dozens of these characters that we spoke to, who were either on their way into it or on their way out. We were very rarely able to speak to people who were in the cutting edge of it in that moment. Of course, the ones who were into it, were either on the run, or didn’t want to talk to us or were suspicious of us, or what have you. But Dane Sweetman’s story became known to us, and we met people who knew him. So that got rolled up into the general research of the thing, but I wouldn’t say that the Dane Sweetman story was the sole inspired to make the film, it was a number of things.

I mean, his story is so horrific and ridiculous. He killed someone on Hitler’s birthday. I remember thinking should we put something like this in the plot? But it seemed so absurd, that anyone would think that we’d just made it up. It was so crazy that you couldn’t even put it in a plot, because it just seemed so contrived.

At the time, obviously you were responding to something that was happening at the time, and a culture of change. There was a lot of reaction for and against the film. Magazines like Premiere listed it in their 25 Most Dangerous Movies. What do you make of that?

[Laughs]You know, to me the whole thing got summed up locally by a guy who was an old fogey back in the ’90s, and he’s still an old fogey, except he’s got a new suit, and he’s had a haircut and a beard trim, and that’s David Stratton. David Stratton led the charge against the film, came out swinging, and was quite hysterical…on the basis that the editorialising in the film was not, in his opinion – according to his taste – overt enough, loud enough and had enough condemnation of its characters. But to us it was very clear that, if you’re watching the film, and you see what happens to these people and how the plot plays out, it’s very obvious that two and two equals four. If you do bad things to other people, it comes back at you and your whole world falls apart.

This is how Shakespeare works. I mean, Shakespeare made Richard III out to be an engaging figure, a compelling figure, a character with a lot of physical courage. Yet certain aspects of him were commendable, but that didn’t make him a commendable man. Just because we said that Hando had certain attributes as a leader, that didn’t make him a commendable young man. I always resented the fact, especially in this country, that if you wanted to tell a story about bad people, the editorialising and commentary had to be screamingly loud and blunderingly crude in order to justify the making of a story. We thought it was much more fun – in terms of being storytellers, in terms of the delight in the complexity of what we were doing – it would be a lot more fun and engaging to say to the audience we’re going to put you inside the gang, we’re going to give you a character with certain things about him that would be positive in different circumstances. And yet you can still see where this all leads you. It’s a but like saying ‘Was Hitler cruel to domestic animals?’ The answer to that, for the most part, was no. He has an Alsatian called Blondi that he loved. He ended up poisoning the dog because he wanted to test the poison he was going to use on himself and Eva Braun. What I’m saying is that if we’d had scenes where Hando was a dog-kicker, or something like that, then David Stratton would have approved. But that wasn’t what we wanted to do. It was of no use to us in our intentions of saying to the audience ‘Come inside the middle of this gang’, experience the rush and adrenaline of it all, and see how it all turns to hell.

Which is why the film is back on the slate 20 years later. If we’d have done it his way, we wouldn’t even be having this conversation. That’s the route that got taken with movies like American History X (1998). They’re good films, but they’re also films that you can stay at arm’s length. They’re easy to stand apart from, and they’re not controversial. I thought it was necessary to be controversial. The delight as storytellers that we took, that we had a taboo theme, we wanted to explore it, this is the way we do it.

You just touched on this briefly, but do you think that notion of Australian films having to be seen in a particular way, or having a particular voice. Do you think that’s changed in the last 20 years?

No, not really. I think that it would be very difficult to make a film like Romper Stomper these days. I think that there would be too many questions in parliament, [laughs] on a state level if it’s Film Victoria. I think these days, people are much more inclined to be politically correct. I think that’s too bad, because it means that things around you in pop culture tend to be pretty predictable, and they tend to be disposable too. They tend to be things that you can put in little boxes and stack neatly and put away in some vast warehouse, and move onto the next thing as if the last thing never happened. Everything is kind of disposable. If you take the approach we took, which was controversial in its day and still is, then it’s not so easy to dispose of it.

In trying to be controversial, and you’ve mentioned Shakespeare, were there any influences you looked at? Were there any classical or film influences you looked at when you were moulding that film.

I think Quadrophenia was probably something we took a good look at, because of the big fight scene on the beach between the Mods and the Rockers. That would have definitely factored into our thinking. In terms of using the camera, and the decision to use Super 16 because we wanted to go handheld, because we knew how much action we had, and we knew that we wanted to engage the audience. Any movie made around that time that had a lot of mobile cameras, we were very interested in.

Of course, one of the things that a lot of people will want to talk about now is the casting, which may seem like incredible foresight given the career Russell Crowe’s had in the last 20 years. My understanding is that he wasn’t your first choice, or wasn’t an immediate choice for you anyway.

Well, he was my first choice, but there was some debate amongst us. We had a discussion with the producers, and what we’d done is created a shortlist of possible young male leads. You can probably imagine whose names would have been on that list back in those days. People who are in their 40s now but were just starting out would have appeared on that list. There were some good people. But I saw Russell in Proof, and I thought that’s the man. Forget about the list, this is the man, this is the guy. So there was some wondering, but it all ended when I saw Proof. I just knew it had to be him.

What qualities did you see in him?

I think there was a brooding and intense quality about him in that film, which may not necessarily been entirely appropriate to that film [laughs], but it was certainly highly appropriate to our film. So I thought he’s going to be a lot more at home in a movie like Romper Stomper, and I thought we can use these qualities that he seems to radiate that weren’t necessarily being used to the greatest effect in a movie like Proof. Because it didn’t have to be, the film wasn’t about those kind of things he was radiating. All of a sudden all of that 12-cylinder power can be put to good use.

You’re worked in various markets, and I’m looking at something like Cherry Falls. Is there anything we as an industry can learn from the US?

I think the mistake we made up until recently is that we didn’t develop writers, we didn’t develop enough of them. We certainly developed a lot of good actors, and in the old days especially a lot of good DOPs. We’ve always developed a lot of good actors, because they’re very rugged individuals. The men and the women do well in the British and American scene because they have a ruggedness about them. They take on projects in Hollywood that I think their American counterparts would be worried about. Our people grasp these opportunities with both hands. What we haven’t done, in my opinion, there is a strategy to empower producers in this country. If that was a way to achieve some kind of sustainable success, let there blossom one thousand production companies. We empowered a lot of producers. I think, and I still think this is wrong, the principal and primary thing to make a movie is a script.

That’s the stuff that goes into the factory and gets turned into a movie. Without it, without the raw material of the script, nothing is possible, and I don’t think we’ve ever paid enough attention to screenwriting. I don’t think AFTRS pays enough attention to screenwriting. In Victoria, although there used to be more attention, there’s less attention now. I think that what I’ve noticed with Screen Australia and Film Victoria, and the New South Wales equivalent of Film Victoria, is they’re much more inclined to defer to American or British script editors to judge work. That’s all very well if you’ve got people trained in Hollywood, or writing in Hollywood, but we don’t. We’ve neglected training wholesale in my opinion So we’re putting them through this Hollywood filter, but we’re not giving them this Hollywood technique to begin with. Neither are we even encouraging them to develop particular techniques that are peculiar to our own situation. Writers in this country have traditionally been paid the worst in terms of profit participation. They’ve been abused, overridden, ignored and otherwise toyed with in the process, and I think now, the chickens have finally come home to roost. You’d have to be completely out of your mind to want to be a screenwriter in this country. The pay is so awful, why would you want to do it?

We’ve already touched on this, and not to labour the point, but I guess the culture of fear in Australia is even more prominent than ever now, as world events impact on local policy. Is a Romper Stomper needed in this current climate, and if you were making that movie now in the current climate, what would your message be?

That’s a pretty big question. Every era brings about its own situation. The complexity of it would require you to be occasionally ambiguous. I think these days to be definitive about something in a way that I wasn’t definitive about certain things in Romper Stomper. It’s a very different situation in many ways. Back in the story about Hando, he was railing and rebelling against a population of people who turned out to be very good merchant stock, who knew how to make money, who knew how to start a business. If you had a Hando these days, contemplating confronting say, a Middle Eastern people, what’s the beef going to be there? In a strange kind of way, what’s Hando going to be defending? Is he going to be defending Western liberal democracy? Or is he going to be – there’s an outfit called the Social Political Alternative, who’s actually quite supportive of the radical Islamic protests, because they see it as a way to make friends with people who can be as angry or as tumultuous as they would like to be. So they can see them as strange bedfellows, which I think is really interesting and really bizarre. A film today with Hando dealing with Middle Eastern people – is that the presumption? I guess so too. Hando would have to have a much more complex game up his sleeve, because there’s so much more grey areas these days. So he would have to have more grey areas. That’s what I mean. What’s he going to do with this situation? Whose side is he going to take, and what is he going to embrace? What does the extreme Right have to say about the extreme Islamic point of view? I suppose the extreme right would take the opportunity to be seen as defending the West. But does that mean defending Western liberal democracy? Well, you might pay lip service to it, but ultimately you don’t want that either. So in a strange kind of way, you don’t want that, and the radical Islamic protesters don’t want that. So it all becomes quite complex and strange. To answer your question, it’s not a plot I’ve flushed out in my head and I don’t have all the answers for you…

I don’t want to put you on the spot!

The bottom line is that Hando would have to play a much more complicated game than what he did 20 years ago.

To wrap up, it’s been a few years between projects, I guess. Is there a particular reason for that, and have you got anything planned?

Ok, the reason for the long gap is very simple and it’s the GFC [Global Financial Crisis], right? I just find that independent films, just forget about it. The last couple of years have been a disaster. I’ve got a project that’s tied up in London, but you can imagine how difficult it is to get money out of Europe for a project. I think that even if things go well, you’re looking at 4 years. So for things to come up against the wall of the GFC, it is very difficult. Having said that, I’ve got a local project I’m hoping to get up next year called Australian Gothic, so maybe that’s what I’ll be doing next year. But I’ve also become a father, and I’ve also dealt with other developments in my own family which were less positive and I’ve done other things with my life. So for all those reasons, I’ve been off the scene for longer than I want, but the time is right for me to come back. It’s time for me to make a movie.

Comments

2 responses to “Exclusive Interview: Geoffrey Wright on 20th Anniversary of Romper Stomper”

Suprised the director did not mention Ben Mendelsohn as I understand he was the lead. I remember like yesterday when they both came to the royal artillery to ask us non racist skinheads about the nazi scene.

I think in real life Dane sweetman stuck a trowl into the neck of an English Skinhead on Hitlers Birthday.The Victim had been making eyes at Dane’s Girlfriend, I believe he ended up Trying to kill his mates.I knew him from going into Port Philph in the 90s.Quite a bright bloke by the end of his sentence,still very much a Nazi.Shame