Life’s a party when Baz comes to town! F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel gets the red curtain treatment.

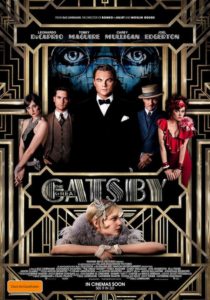

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Great Gatsby (2013)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Baz Luhrmann

Writer: Baz Luhrmann, Craig Pearce

Runtime: 143 minutes

Starring: Tobey Maguire, Leonardo DiCaprio, Carey Mulligan, Joel Edgerton

Distributor: Roadshow Films

Rating: ★★★

More info

[/stextbox]

Despite the lack of alcohol, Prohibition must have been fun. The movies certainly paint it as the most exciting time to be alive since saddles got sore on their journey westward ho. Indeed, next to the Western, the truest form of American filmmaking has often been the tales of cops and robbers coming out of a thirteen-year dry spell of temperance gone mad. From the White Heat of the 1930s through to television’s Boardwalk Empire, the crime that spun out of this period is sexy and almost aspirational. For author F. Scott Fitzgerald, who published The Great Gatsby in 1922, it was a time of social upheaval, great change and extreme decadence. Baz Luhrmann has paid attention to the last bit of that at least.

Paris, 1900. The women he loves is dead. Scratch that. Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire) is a depressed alcoholic in a sanatorium, recounting to a psychiatrist the events that led to his disgust with humanity. During the summer of 1922, he was a Yale graduate and a bond salesman renting a house in Long Island next to the enigmatic Jay Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio). After driving across the bay to visit his cousin Daisy Buchanan (Carey Mulligan), and her husband, Tom (Joel Edgerton), his destiny alters when neighbour Gatsby invites him to a lavish do. Drawn into the world of rich and infamous, Gatsby only has one desire in life: to reconnect with Daisy, the one he thinks got away.

With all of the fine nuance that the description on the back of some crib notes provides, the first half of Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby is a solid remake of his own Moulin Rogue, itself reworking the themes of La Bohème and Romeo and Juliet he had already played with. The first part of the film is undeniably gorgeous, with Gatsby’s lavish soirées the kind of unsubtle spectacular spectacular that our Baz never fails to pull off. Only here is the superfluous 3D an asset, completely immersing the viewer in this world of glitter. It’s unclear as to whether Luhrmann has read the novel, although he does a fairly good job of convincing us that he was at least aware of the period it’s set in. Yet as a drug and alcohol fuelled party erupts in a New York apartment, to the strains of a Jay-Z/Kanye West tune that compares the condition of African Americas to “something like the Holocaust”, one has to wonder if Luhrmann even listened to the songs on his own playlist.

As the film shifts gears into the second and much darker half of the story, Luhrmann makes good on the promise of a modern interpretation of this story. Here the cast get to outshine the sets, and in the case of DiCaprio, he delivers a star turn that might make him the definitive Jay Gatsby. We have no problem in believing in Mulligan’s doe-eyed surface sheen or Edgerton’s arrogant self-assuredness either. It’s only the wooden Maguire, whose droning narration plagues the entire film, that fails to convince in the slightest. His unfortunate intonations barely carry any weight, and his presence is, at least in this screen version, perfunctory.

If The Great Gatsby is a failed adaptation, it wouldn’t be the first, as it’s the writer’s voice that is crucial to selling the narrative. It’s no wonder that the flamboyant leanings of Luhrmann is able to perfectly capture the hollowness of the first half without the corresponding depth of the denouement. As Gatsby parties break out around the world, complete with flapper girls and tuxedoed boofheads, it will be this first half that gets remembered, replicated, remixed and regurgitated until the fad fades. Everything else is merely inconsequential.

The Great Gatsby was released in Australia on 30 May 2013 from Roadshow Films.