In mid-2013, during Doctor Who’s 50th anniversary, one bearded blogger put life and social norms on the line to bravely watch every Doctor Who serial and episode in broadcast order. This is his story.

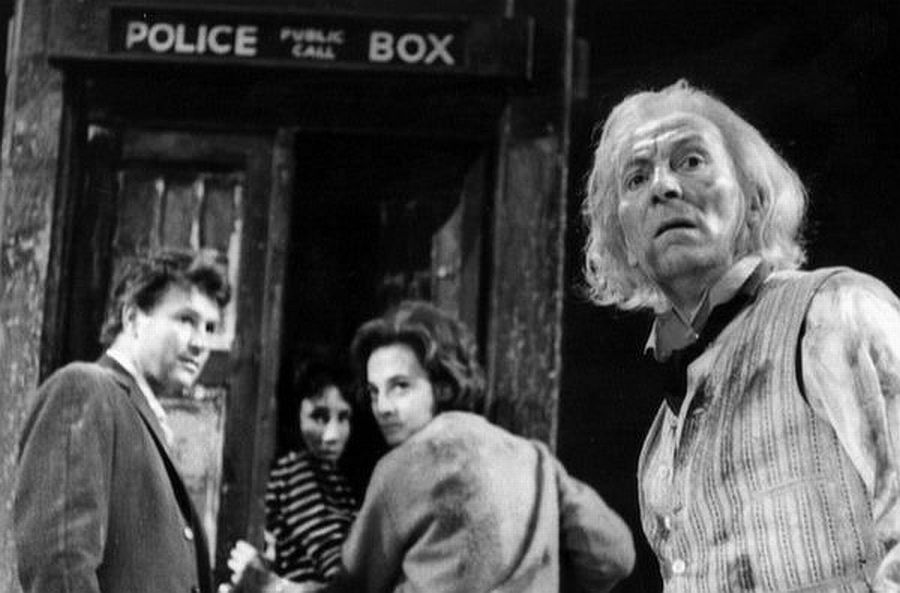

On 22 November 1963, US President John F. Kennedy was fatally shot in Dallas, Texas. With slightly less coverage, the following day saw the UK television premiere of a new science fiction show called Doctor Who. When viewers first saw a couple of school teachers venture inside a strange blue police box sitting in a junkyard, only to find it was bigger on the inside, little did they (or the BBC) know that the premise would become a part of popular culture that would still be standing half a century later. Revisiting this first season is to ask a question that has only recently resurfaced in the television series: “Doctor who?”

Like many folks, I was partly prompted by the moisteningly cool ending of The Name of the Doctor (Series 7, 2013) to go back and watch some of the earlier episodes. Going back to the Russell T. Davies/Christopher Eccleston 2005 reboot seemed far to easy, and the montage of previous Doctors reminded me of how gappy my memory of these episodes was. Indeed, there were large chunks I’d simply not seen, and to my eternal geek shame I’d probably seen more of Peter Davison as a stitch-craft peg figure on Etsy than on the small screen. An additional problem was the huge chunk of missing episodes from the First and Second Doctor’s years, thanks to the infamous BBC junking policy of the time. So the rules were simple: I had to watch everything in whatever format I could get my hands on, including the official and unofficial reconstructions of the missing episodes. (There’s some wonderful stuff available on YouTube for the curious, combining stills and off-air recordings of the audio. It’s actually quite a lyrical way to watch vintage television).

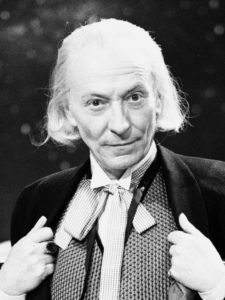

The Doctor (William Hartnell) is first introduced unceremoniously inside a junkyard. Worrying about the strange behaviour of student Susan (Carole Ann Ford), school teachers Barbara (Jacqueline Hill) and Ian (William Russell) decide to follow her home to her enigmatic ‘grandfather’, and quickly become drawn into the TARDIS and its many adventures through space and time. Despite limitations with budget and special effects in 1963, a little bit of elbow grease and imagination make these some of the more ambitious episodes of the entire run. The first three serials (available as part of the insanely cheap Doctor Who: Beginnings DVD box set) are about as different from each other as you could get, but set the template for the types of stories still being told 50 years later. An Unearthly Child (aka 100,000 BC) takes us to the distant past, with some primitive factions fighting over fire, and while it all goes on a bit long (a characteristic of many of the classic Doctor Who serials), although it neatly lays out how the dynamic of these four characters would work together over time.

The introduction of the Doctor’s most fearsome foes in The Daleks is a far cry from the universe shattering events seen today, with their intro being just as mysterious as that of the Doctor. Some of their history has been retconned in a Davros-heavy future for the characters, but the first terrifying appearance of a plunger coming into frame is more frightening that a plumber’s bill. At seven episodes, it definitely overstays its welcome, but is also not the longest Dalek story by far. (That honour would go to the staggering 12-episode partly missing serial from the third season, The Daleks’ Master Plan). By the middle of the run, we’re wandering around swamps and caves, but that seems as logical a place as any to hide from an alien species that was getting about on wheels at the time.

The real curiosity from this early bunch is The Edge of Destruction, a two-parter set entirely inside the TARDIS. After waking up to find themselves with minor amnesia, all of the crew start turning against each other, suspecting foul play. The Doctor goes so far as to drug his companions to stop further interference in his investigations, just one of the many differences in this early version of the Doctor. It’s hard to conceive now, but as these were written, there was no thought of him being the first of many incarnations. Hartnell was carving out his own piece of television history, and there are times when you can almost hear him trying out the sound of the Doctor’s voice on screen. In this “bottle episode” we get a distillation of all the mysteries that surround a character we didn’t even know was a “Time Lord” from “Gallifrey” yet.

The companions, on the other hand, were an interesting attempt to balance out the educational and adventure aspects of the show, a line that the episodes straddled for much of these early years. After all, two of them are schoolteachers. When Susan is introduced, she’s as enigmatic as The Doctor, albeit dancing like a fool to John Smith And The Common Men. It’s a shame then that some of these episodes reduce her to running or fainting, a partial reason for her eventual departure in the show’s second season. In The Sensorites, she and Barbara are given the task of preparing the meals for the boys, and fetching the water (which is what brings them into contact with the aliens in the first place). Yet from Marco Polo onwards, it’s clear that an effort was being made to give each of the companions their own spotlight by often splitting them up for dramatic effect.

Marco Polo in itself is a interesting piece of repeat viewing. As this one is completely missing, I was forced to resort to the wonderful Loose Cannon reconstructions that can be found around the place. It’s another lengthy one at 7 episodes, perhaps made all the longer by watching it in stills with audio only, and should be a prime candidate for animation if the BBC coffers can handle it. Yet there’s an epic quality to this particular serial that’s hard to quantify, and the extended runtime gives us the sense of having been on the road with these weary travellers for weeks. The splitting up of the companions and the Doctor was a repeated motif through the series, followed immediately by the interesting concept of The Keys of Marinus. That was the first “quest” type episode, where each episode would see the crew off to find one of the titular keys in a different location. It doesn’t always work, losing some of the momentum midway through, but it was an early indicator of the ambition of the show. It’s also interesting to view this as a precursor to the extreme version of this that would see Fourth Doctor Tom Baker search for segments of The Key to Time across 6 serials in the sixteenth season.

This is a very different Doctor Who for fans of the modern serials. He’s cranky, often chastising his companions and relegating women to the TARDIS equivalent of the kitchen. He often urges caution in place of unrestrained gleeful exploration, and the “Barbara story” in The Aztecs is a prime example of this. When Barbara finds herself worshipped by the ancient Aztec peoples, she vows to put an end to human sacrifice. “You can’t rewrite history,” warns the Doctor. “Not one line!” However, this is one of the major themes of the show, as they change some minor thing every time they leave the TARDIS. Later Doctors would have a cavalier attitude to time, while the 2005 episode Father’s Day would look at the impact of trying to change your own timeline. This was actually one of the first Hartnell episodes I had ever seen on my initial viewing years ago, so I’ll always have a soft spot for it, especially given that there’s a comic subplot that sees the Doctor inadvertently engaged to a local, following a mix up involving hot cocoa. Ian also gets to be the default action man of the series, fighting some warriors to the death for some reason I’ve already forgotten. Plus, I was learning while having fun, which is a win-win really.

The final serial for the first season is partially missing, but thanks to the boffins at BBC, we have the missing fourth and fifth episodes animated for our viewing pleasure. The Reign of Terror is an odd bird, in that it’s an historical episode that assumes the viewer already knows the history of the French Revolution. Kids were far more cluey in those days, prior to losing themselves in mobiles, 3D teleboxes and flavoured wheat grass. It was a bit of a thrill seeing Hartnell getting about in full uniform, clearly having a ball doing so. It’s not all good, with Susan getting an unspecified illness that was probably more indicative of the writers not knowing exactly what to do with her. However, as the episode (and the season) draws to a close, we get this wonderful coda from Hartnell, which is one of the first great sign-offs from the Time Lord: “Our destiny is in the stars. Let’s go and search for it.”

So with 42 episodes down, and only 750 remaining, the marathon continues. While it is unlikely that I’ll polish all of these off before the end of the 50th anniversary year, I’m now deep into the show’s second season (having just entered The Chase, a time-travelling Dalek story), and show no signs of slowing down. As wonderful as the new episodes are, these early ones really give us an idea of how much imagination and sheer bootstrappery that got the BBC cast and crew through on the smell of an oily rag. It’s this firm sense of the show’s history that I was seeking in pursuing this madness, and boy did I learn about history.

Next time: Giant ants! Daleks on Earth! Vicki! Giant moths! PLUS The Meddling Monk!

Stay tuned!

Comments

1 response to “‘Doctor Who’ 50th Anniversary Marathon Recap: Season 1 (1963 – 1964)”

I love this. It give a great recap of the origins of Doctor Who