The 17th Japanese Film Festival opens up with The Great Passage, and it’s a refreshing earnest film that will stick with you, says Alex Doenau.

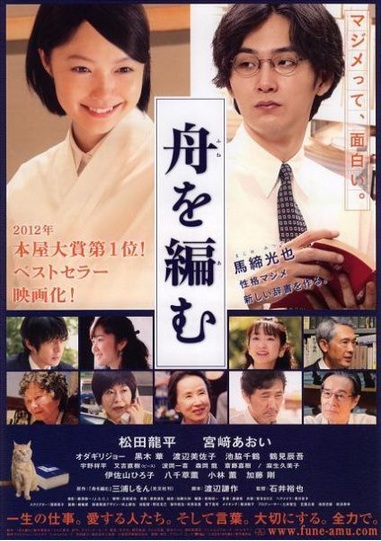

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”The Great Passage (2013)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Runtime: 133 minutes

Starring: Ryuhei Matsuda, Aoi Miyazaki, Joe Odagiri, Kaoru Kobayashi

Country: Japan

Rating: ★★★★

More info

[/stextbox]

The general rule of Japanese entertainment is that any subject is fit for a story. This is how a best seller can be written about the compilation of a dictionary and how, in time, it can become a film. The Great Passage (舟を編む) is a sprawling and surprising tribute to a process and the people involved in the undertaking. It’s quite nice into the bargain.

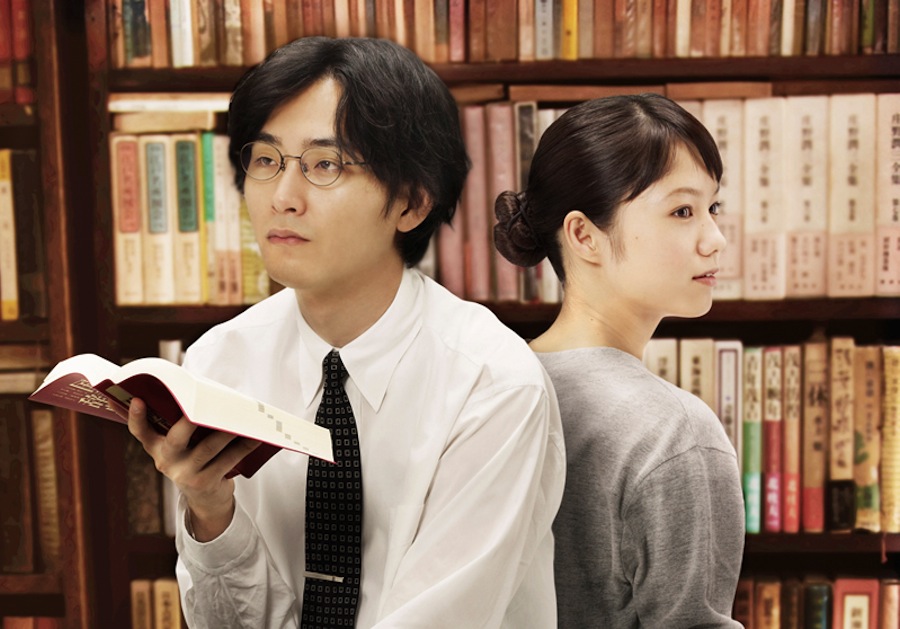

The year: 1995. The dictionary editorial team at Genbu Books are trying to compile a living dictionary, more comprehensive than any other dictionary on the market. When shy worker Majime (Ryuhei Matsuda) joins the team, his passion for words transforms him into a diligent enthusiast. The Great Passage tracks the compilation of the titular dictionary over fifteen years, and follows Majime’s fledgling relationship with his landlady’s granddaughter Kaguya (Aoi Miyazaki).

As a dictionary, The Great Passage is an ambitious project, but the film is less of a gambit. The core team of four members is presented as a cohesive unit and are instantly likeable. Even though Majime is socially awkward to the point of coming across as a high functioning autistic, the movie never makes cruel fun of him. In the initial stages the movie’s understated love story is introduced, not as a distraction but as an extension of Majime’s own ideals. His character is a mystery even to himself and it’s a pleasure watching Matsuda unfolding the role.

The Great Passage‘s basis in a popular novel is only apparent in that it has characters with story lines separate to the dictionary that are merely hinted at, and a sudden thirteen year time leap with the introduction of a new character is abrupt before it feels organic. Ultimately the passage of time is essential and the addition of a new outsider throws the rest into relief, but in a smooth film with few jarring notes (excepting the literal jarring notes of Takashi Watanabe’s at best awkward and at worst awful score), it sticks out.

Later parts of The Great Passage would likely horrify people who believe in labour rights and unions, but we are asked to glorify the dedication and the industriousness of the workers who sacrifice their health and social lives so that their project can become reality. The value of a good work ethic is held up in a ridiculous fashion when the previously tyrannical managing director shows up to give his extended (and one presumes largely volunteer) staff free cans of coffee. Narrative satisfaction and western work standards are at odds just this once.

As The Great Passage draws to a close, one can’t help but wonder “what comes next?”, and the answer is so logical that it seems inevitable. Refreshingly earnest and quietly funny, The Great Passage is a movie that believes in the importance of its subject matter. It’s an unlikely fit for a film, but unlikely films are often the ones that stick with you.

Comments

1 response to “JFF 2013 Review: The Great Passage”

The version of this review forwarded by google subscriptions looks as though it has been hacked, as comments about viagra and cialis are interspersed throughout the piece.