The final Studio Ghibli film (for now) is a bittersweet farewell to an era.

[stextbox id=”grey” caption=”When Marnie Was There (2014)” float=”true” align=”right” width=”200″]

Director: Hiromasa Yonebayashi

Writers: Keiko Niwa, Masashi Andō, Hiromasa Yonebayashi

Runtime: 103 minutes

Starring: Sara Takatsuki, Kasumi Arimura

Distributor: Madman

Country: Japan

Rating: 8/10

[/stextbox]

When news came down last year that Japan’s foremost animation house Studio Ghibli would be halting future productions following the retirement of founder and father figure Hayao Miyazaki, it seemed like a piece of the global consciousness was going along with it. For the last three decades, the company’s films have been given almost universal acclaim, from the earliest days of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind through to international sensation Spirited Away. The last few years have been in flux, as showcased in the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, chronicling the production of Miyazaki’s last film, The Wind Rises and Isao Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. With WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE, the studio concludes an era with some familiar magical realism.

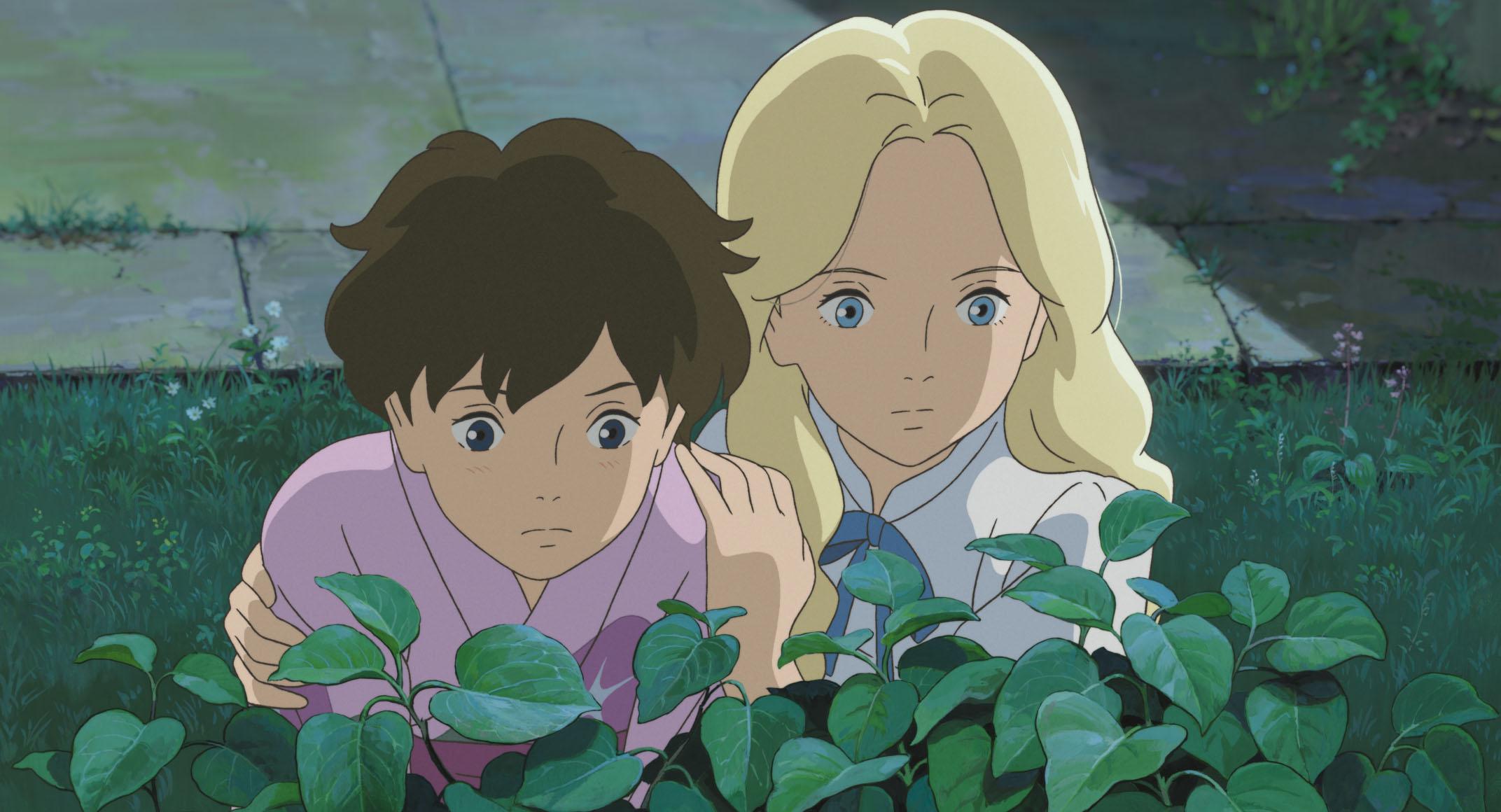

It’s certainly fitting that what just might be Ghibli’s last film has a very traditional set-up, based on the English novel of the same name by Joan G. Robinson. After being increasingly withdrawn, 12 year old Anna Sasaki (voiced by Sara Takatsuki) has an anxiety driven asthma attack and is sent from Sapporo to spend the summer with relatives in the fresh air of the seaside town of Yoriko, Kushiro. She quickly becomes captivated by a dilapidated mansion across the marsh lands. Haunting her dreams, she begins to visit Marnie (Kasumi Arimura), the little girl who apparently lives there. All is not as it appears, however, as Anna’s summer away becomes a voyage of self-discovery.

On the surface, WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE is a classic ghost story, with Anna literally and figuratively visited by figures from the past. Yet there is a really important subtext about dealing with anxiety and depression as well, a conversation aimed at young audiences which is deftly handled here. Anna’s “asthma attacks” do seem to be closer to panic attacks, and her ennui is something that none of the adults around her seem willing to acknowledge or explain. Frequent references are made to her “going away to get better,” a parallel that becomes important later in the film with the revelation that one of her relatives also spent some time in a sanatorium.

Like many Ghibli films, or indeed children’s literature generally, it deals with these important moments of coming-of-age via the vehicle of escapism. Compare it with the recent Disney film Frozen, as suggested by artist Damian Alexander, where Elsa is taught to “conceal don’t feel, don’t let it show.” Here, the film boldly opens with a lead character who is isolated and depressed, viewing her surroundings through an elaborately detailed sketching she is creating, as Anna narrates the following before collapsing:

“There is a magical circle in this world that no one can see. Those girls are in the circle, and then there’s me, on the outside. But I don’t care about any of that. I hate myself.”

Lashing out her peers, she desperately wants to have a life that is “normal”. As the film progresses, this isn’t dealt with head-on as it would in a less subtle film, but rather in the transition from an ambiguous “fantasy” relationship to a real one with another neighbourhood girl. Here the world literally changes around her as she approaches her peace, demonstrating that it is an inner journey and not something that can be handed to you by someone else. It’s a really important discussion of this issue, and one that is dealt with maturely and with respect. Like most fairy tales, they teach children (and all viewers for that matter) the importance of actualising your fears, giving them a name and realising they have a conclusion.

A gentle remembrance of things past, it’s the kind of film that Ghibli does so well in films like Takahata’s Only Yesterday or Tomomi Mochizuki’s Ocean Waves. When director Hiromasa Yonebayashi made his theatrical debut a few years ago with The Secret World of Arriety, another adaptation of a classic English novel, he became the youngest director to do so at the age of 37. This may only be Yonebayashi’s second feature, but he has been working on Ghibli films since 1997’s Princess Mononoke, and the film drips in studio style. It shows in the animation, a gorgeously realised vision of a small town that smacks of authenticity, using colour and light judiciously to create atomosphere out of what is essentially a narrative crafted around two of three main locations.

If this truly is the end of the road for the current iteration of Ghibli, then the studio is going out with the same level of grace and poignancy that they have brought to all of their films to date. It may not have the comedic whimsy of My Neighbour Totoro or the high adventure of Spirited Away, but it is nevertheless an important film with a good heart.

WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE was released in cinemas in Australia on 14 May 2015 from Madman.