Summary

Oliver Stone’s reminder that you’re not paranoid if they really are out to get you is a rework of recent history that focuses on the individual rather than the cause.

“No matter who you are, you’re sitting in a database just waiting to be looked at.”

By virtue of clicking on the link that led you to this review, you’ve contributed to the massive amounts of data that is being collected about you. Your search histories, your credit card purchases, your Über rides, your PokémonGo checkins, and your emails all form a digital fingerprint that indicates to a data collector who you are and what you might do. It was an awareness that the National Security Agency (NSA) in the US was collecting this data on millions that led Edward Snowden to blow the whistle on the agency, and covertly release top secret information to the media.

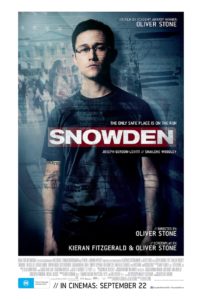

Previously the subject of the award-winning documentary Citizenfour, Oliver Stone’s fictionalised account of Snowden (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) attempts to uncover the reasoning behind his actions. Opening in Hong Kong in 2013, we follow Snowden’s military career, as CIA boss Corbin O’Brian (Rhys Ifan) takes him under his wing. During this time, Snowden forms a relationship with girlfriend Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley), and ultimately reveals government secrets to a trio of journalists (Melissa Leo, Zachary Quinto and Tom Wilkinson).

The bigger question of whether Snowden is a whistleblower or a traitor is never questioned by Stone’s biopic. Establishing the lead as a patriot through some heavy-handed dialogue early on (“I don’t like bashing my country”), a portrait is painted of a man who was frustrated at his ability to do a job in a post-9/11 world where information is king. “Terrorism is the excuse,” we are told. “The only thing we are protecting is the supremacy of your government.”

Gordon-Levitt disappears entirely into the role of Snowden, convincingly earnest and pragmatic as both a true believer and a paranoid informant. His body language carries a quiet confidence that comes with intellect, and a flightiness that follows excessive access to knowledge. The trio of journalists are bang on the money, with Wilkinson in particular spookily accurate as Scottish Guardian journo Ewen MacAskill. Woodley, in the key role of the real-life Mills, works with a light-touch script for some force-fed emotional moments. Yet she is far less perfunctory than Nicolas Cage in a bizarre pseudo life coach role, with actual dialogue that includes “You did it kid!”.

The technical aspects of the film sometimes fail the lofty messages, perhaps a indicator of the budgetary constraints Stone faced. Much of the film is spent inside the Hong Kong hotel room that served as the setting for Citizenfour, robbing SNOWDEN of the global scope it espouses. At other times, Rhys Ifan menacingly looms over Gordon-Levitt on a video screen like something out of Brazil. Stone is known for his long films, and while this clocks in noticeably shorter than JFK or Nixon, the meandering narrative could still do with a damn good edit.

One of the ironies of SNOWDEN is that the eponymous figure repeatedly warned of the dangers of making him the figurehead of the movement, rather than focusing on the bigger issues he actually revealed. Blending fact with a little bit of fiction, the bigger picture is where the strengths of Stone’s film lie, reminding us that the right to question leaders is one of the cornerstones on which the US was founded (even if those leaders did keep slaves at the time). At the very least, you’ll probably be placing tape over your device’s camera about now.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2016 | US | DIR: Oliver Stone | WRITERS: Kieran Fitzgerald, Oliver Stone | CAST: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Shailene Woodley, Melissa Leo, Zachary Quinto, Tom Wilkinson, Scott Eastwood, Timothy Olyphant, Rhys Ifans, Nicolas Cage | DISTRIBUTOR: Buena Vista International (AUS), Open Road Films (US) | RUNNING TIME: 134 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 15 September 2016 (AUS), 16 September 2016 (US) [/stextbox]