Film has always been about “the gaze” to some extent, with the images and people on screen sharing a kind of symbiotic relationship with the viewer. The oft-cited Jacques Lacan talks about the gaze in terms of the subject losing autonomy when they realise they are being viewed as an object. When we think about Alfred Hitchcock’s mastery of this notion in Rear Window (1954), we remember those classic moments of the reverse of power when the observer becomes the observed. Of course, the latter is also an example of Laura Mulvey’s contention that cinema’s “male gaze” is representative of gender asymmetry in film, as it is cinema that determines who is observed and who does the observing.

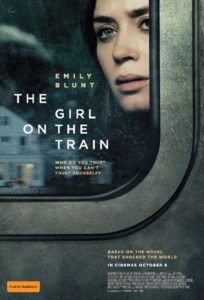

So it’s a shame that while THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN firmly flips the gender of the gaze, it doesn’t break any other thriller conventions in the process. Alcoholic Rachel (Emily Blunt) has never emotionally recovered from her husband (Justin Theroux) cheating on her and leaving their marriage for another woman (Rebecca Ferguson). Eking out her existence by people-watching on a daily commute to New York, she fixates on the relationship between her former neighbours Megan (Haley Bennett) and Scott (Luke Evans), representatives of the “idyllic” life she feels she lost. This radically changes when she witnesses something from the train and Megan goes missing.

Beneath the time shifting and blackout moments, director Tate Taylor‘s film is a fairly straightforward thriller. Adapted from the 2015 novel by Paula Hawkins, screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson retains the first-person narrative (and all the constructed gaze that comes with it) in the translation. It’s not an easy fit, with the plodding pacing and melancholic voice-overs dragging the speed of this locomotive to a slow order. Like the near nudity and sex scenes frequently obscured by trees, THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN gives us the illusion of glimpsing a far more exciting world than we actually are. This is because the film relies on deliberate obfuscation to produce its tension, but once you’ve cracked the code it stays on a steady track for the remainder.

Blunt certainly makes at least some of the experience worthwhile, putting her all into a performance of a blackout drunk, one that transcends the one-dimensional material she’s given. Her gaze makes the film unfold like the memories she is desperately trying to recover, and her mixture of desperation and sadness is palpable. While she is surrounded by an excellent cast of otherwise acclaimed actors, they are all forced to make stupid decisions in order to avoid the obvious conclusions for a few hours. Allison Janney, as the investigating Detective Sgt. Riley, appears to purposefully and belligerently overlook vital evidence in a baffling turn that really adds very little to the overall narrative.

As a boozy stab at transposing the male gaze, Blunt is far more fascinating that the things she is witnessing. At best, the film might open up a conversation about abusive relationships. Yet by the final clumsy act, THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN tries to combine familiar themes from Rear Window and Gaslight, but this film is not built to the same standard gauge. When the film attempts to bring all of the disparate threads into the station, the final scenes throw a whole lot of new information at the audience at once, with a few convenient changes of heart and mind that come out of the blue. Indeed, the whole film is exactly like sitting on a train and watching someone else’s life speed by, and the glimpses we catch are not enough to sustain our interest for long.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2016 | US | DIR: Tate Taylor | WRITERS: Erin Cressida Wilson (Based on the novel by Paula Hawkins) | CAST: Emily Blunt, Rebecca Ferguson, Haley Bennett, Justin Theroux, Luke Evans, Allison Janney, Édgar Ramírez, Lisa Kudrow | DISTRIBUTOR: eOne (AUS), Universal (US) | RUNNING TIME: 112 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 6 October 2016 (AUS), 7 October 2016 (US)[/stextbox]