There’s a scene in HELL OR HIGH WATER where a rancher complains that running cattle from a fire feels out of place in the 21st century. Director David Mackenzie is well aware of the anachronism that his neo-western represents in the cinematic landscape, being unapologetically modern and simultaneously a throwback to classic constructs. In fact, Mackenzie and Sicario scribe Taylor Sheridan mostly use the genre shopfront as a commentary on the power of banks in this thrilling anti-heist film.

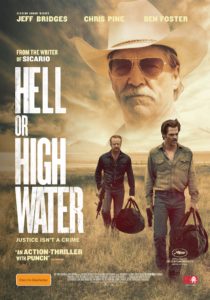

Divorced father Toby Howard (Chris Pine) and his brother Tanner (Ben Foster) carry out a series of well-planned bank robberies in West Texas, although Tanner’s reckless nature threatens to get them caught. Texas Rangers Marcus Hamilton (Jeff Bridges), who is nearing a forced retirement, and Alberto Parker (Gil Birmingham) are sent to investigate the crimes. Both groups are driven by complex histories that underpin their actions, hurtling towards an inevitable conclusion that neither wishes to acknowledge yet.

The tension between the past and present runs deep throughout the film. Toby and Tanner have a dark backstory with their father, killed in a “hunting accident.” Hamilton’s relentless racial teasing of Alberto’s mixed Mexican/Native American heritage acknowledges a massive cultural past at war with the modern world. More literally, the baton passing between Hamilton and Alberto smacks sharply of a lighter version of Cormac McCarthy/the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, with Hamilton both realising that his days are over but unable to quite give it up. In the most telling moment of the film, Alberto reminds Hamilton that his ancestors were once the “Indians,” and the same will be true when a future civilisation overthrows the current one. Coupled with the suggestion that financial institutions are the current invaders, the wasteland of industrial poverty that surrounds them all is indicative that our empire has already begun its decline.

The formidable and well-assembled cast centres on Pine’s steely gaze, and Foster’s shambolic character as a contrast. Yet it’s Bridges dry West Texan drawl, pushed out as if through first chewing the words, that the film hangs its hat on. Birmingham’s mixture of exasperation covering bemusement is spot-on, and special mention needs to be made of the ubiquitous character actress Dale Dickey.

HELL OR HIGH WATER is also spectacularly shot by Giles Nuttgens (The Fundamentals of Caring), with the vistas of east New Mexico standing in for West Texas. Epic skies contrast against simple structures and oil fields alike, with a growing sense of foreboding achieved by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’ atmospheric score. This is punctuated by country voices in the vein of Gillian Welch and Townes Van Zandt, the kind you can imagine listening to while sitting on the porch and watching the world grow old.

Slickly produced and cleverly woven together, HELL OR HIGH WATER is a much-needed skewering of the intricacies of modern life wrapped inside the deceptively simple morality tale of family and other partnerships. “You’ll never be done with this,” muses Bridges in the film. “It’s going to haunt you for the rest of your days.” The same could be said of the film, and at the very least it will certainly give you much to ponder.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2016 | US | DIR: David Mackenzie | WRITERS: Taylor Sheridan | CAST: Jeff Bridges, Chris Pine, Ben Foster, Gil Birmingham | DISTRIBUTOR: Madman Films (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 102 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 27 October 2016 (AUS), 12 August 2016 (US) [/stextbox]