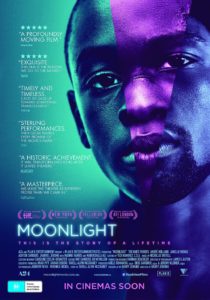

How do you define your own identity? For most of us, it’s a chore to find where we fit in the world. For a diminutive and withdrawn black child in gangland Miami, discovering the first notions of his sexuality, its a lifelong struggle. Barry Jenkins’ second feature is a powerhouse of performance and mood, a mellow musing on the very stuff that makes us who we are.

Based on a play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, MOONLIGHT is divided into three acts. We meet the shy Chiron (Alex Hibbert), relentlessly teased and beaten by his classmates, and labelled ‘Little’ for his size. Living with his substance-abusing mother Paula (Naomie Harris), his only solace is classmate Alex and de facto father figure Juan (Mahershala Ali), a local crack dealer who lives with his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

Opening with a long 360 degree shot of Chiron’s neighbourhood, Jenkins’ camera visually guides us into his worldview. Frequently shifting in and out of focus, Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton (Yoga Hosers) show Chiron’s disconnection. In fact, almost nothing is overtly spoken or shown: a reddish glow from Chiron’s mother’s room, for example, is our first indication that she’s a sex worker. Segues through three act structure take the form of short flashes of multicoloured lights, putting full stops on critical moments and transitioning us into the next phase of Chiron’s life. It reinforces the importance of these defining moments in a life, but is mellow enough to suggest that they can sometimes be informative rather than transformative.

Following the emotional gut-punch of the first act, with a powerhouse performance by Ali playing across the young Hibbert, the teenage Chiron (Ashton Sanders) is openly harassed by a classmate, but he is still close to Kevin (Jharrel Jerome). Two key sequences define this section of the film, each at either end of the emotional spectrum. The first is a tender moment on the beach between Chiron and Kevin, bathed in the soft and comfortable lighting of night that suggests both intimacy and trepidation. It’s almost immediately followed by a violent clash, a life-changing moment that ends Chiron’s youth.

The third act is perhaps the strongest in terms of its immediacy. In a section entitled ‘Black,’ referring to Kevin’s teenage nickname for Chiron, the adult Chiron (Trevante Rhodes) is now a much harder and physically imposing drug dealer. In reconnecting with Kevin (André Holland), Chiron finally allows himself to examine who he really is. The notion of inventing and reinventing “self” is reflected in Kevin, now a cook in a diner, and Chiron’s mother, who is recovering from addiction. Jenkins’ script lets us figure out the spaces between the dots, and how much pain reaching these points has caused his players.

“At some point, you gotta decide for yourself who you gonna be,” Juan advises a young Chiron early in the film. What that sage bit of advice doesn’t encompass is the number of selves we decide to be at various stages in our lives. Jenkins’ tale is a deeply personal narrative, one that doesn’t necessarily get Chiron to that place of self-assuredness by the end, but it does provide hope to the hopeless.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2016 | US | DIR: Barry Jenkins | WRITER: Barry Jenkins | CAST: Trevante Rhodes, André Holland, Janelle Monáe, Ashton Sanders, Jharrel Jerome, Naomie Harris, Mahershala Ali, Alex Hibbert | DISTRIBUTOR: Roadshow Films | RUNNING TIME: 110 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 26 January 2017 (AUS), 21 October 2016 (US) [/stextbox]