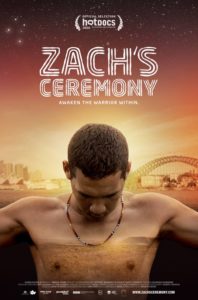

If the antidote to ignorance is knowledge, then ZACH’S CEREMONY might be the cure to what ails a nation. Cultural ambassador and media personality Alec Doomadgee began filming his son Zach at the age of 10, and over the course of the next six years traced his journey towards a traditional initiation into manhood. As a film it is fascinating, but as a message it’s an exemplar in making the changes one wants to see.

The titular documentary subject is presented at typical of any 10-year-old, someone who is desperate to grow up quickly but is yet to find a context for what that means. Yet for Sydney-based Zach that also means being caught between the modern world and an ancient culture, a heart divided against itself, exacerbated by the estrangement of his parents and a tangible distance from his culture in north Queensland.

Doomadgee has an unfortunately common story among Indigenous communities in Australia. In the 1930s the land was overtaken by missionaries who promptly banned the use of language and ceremony. Len Cubby, Zach’s maternal grandfather, was forced into missionary work. The legacy of this cultural attack, coupled with the fines and imprisonment associated with the severe Alcohol Management Plan penalties, has left people like Zach displaced from their communities. Indeed, suicide rates in the community are as high as 14 out of 1000 in Doomadgee according to the documentary, including one of Zach’s cousins who died during production. An excellent animated segment (embedded above) showcases the impact of European settlement in Australia, and that alone makes ZACH’S CEREMONY an important teaching tool.

If the footage and narrative seems revelatory to many audience members, it’s because director Aaron Peterson has been allowed unprecedented access to the culture. The permissions granted to him coming partly from the work that Alec Doomadgee had done prior to Peterson’s involvement, filming Zach from an early age and introducing his boundless personality and passion for sharing and passing on the culture via cameras to the rest of his community. It isn’t just aspects of the initiation ceremony that are opened up to us either, with raw and emotional footage of both Alec and Zach confronting their personal demons gripping viewing. To Peterson’s credit, he doesn’t end the film at the obvious point of the ceremony either, staying with Zach and Alec long enough to impress upon us the importance of the initiation to Zach’s life and his life in Sydney. As we follow him Boyhood style past his 16th birthday, Peterson and his subjects provide us with important contextual meaning.

For a viewing audience, the journey is a satisfying one, as the Audience Award at last year’s Sydney Film Festival attests. Yet it’s nothing compared to the impact that it’s had on the Doomadgee family. In recent interviews, Zach spoke of extending his father’s work into a film about Aboriginal women in community directed by women. Some will find the newfound knowledge confronting, but it is important that that this film gets a broad audience and is continued to be played a lot until Australia begins to work together to remedy some historical wrongs.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2016 | Australia | DIR: Aaron Peterson | WRITER: Sarah Linton | CAST: Zachariah Doomadgee, Alec Doomadgee | DISTRIBUTOR: Wangala Film (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 93 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 30 March 2017 (AUS) [/stextbox]