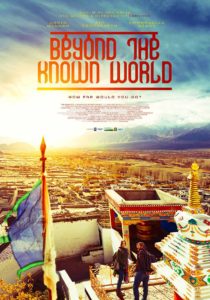

Between Lion and Hotel Mumbai, antipodean cinema has been fascinated with the relationship between India and our world travelling nations. Indian director Pan Nalin has spent a career showcasing different aspects of his home, and the popularity of films such as Samsara in Australia and New Zealand undoubtedly contributed to this continuing imagery. BEYOND THE KNOWN WORLD combines this appeal with a parent’s worst nightmare, crafting a rounded vision of petit enlightenment.

Estranged New Zealand couple Carl (David Wenham) and Julie (Sia Trokenheim) reunite when their 19-year-old daughter Hannah fails to return home from a trip to India. Fearing the worst, they set off on a journey through the Himalayas to find her. Encountering a culture they don’t understand, they slowly come to learn some new truths about Hannah through the lens of people whose experience mirrors their own.

BEYOND THE KNOWN WORLD is a film of contrasts, not just of the New Zealanders adjusting to India, but where tranquil moments are suddenly intercut with a tribal dance club. Wenham’s character is like a bull in a china shop, while Trokenheim’s is unable to accept anything beyond her version of Hannah’s fate. Yet as their perspective shifts, so does the tone of Nalin’s film. Aging hippie Louise (Emmanuelle Béart) and the young tourist Astrid (Chelsie Preston Crayford) offer possible bookends for Hannah’s unknown path, with the former admitting that her life would be very different if her parents had ever gone looking for her. Carl and Julie’s actions negatively impact Astrid, on the other hand, giving them pause to reflect upon how their own relationship has influenced Hannah.

Stunningly shot, cinematographer Ian McCarroll (Fantail) offers a unique perspective on the landscape. Showing us aspects of a country we don’t often see, gorgeous waterfalls and incorruptible police are at odds with stereotypical preconceptions. Similarly, the gentle score guides the audience towards an observatory mode where we get a sense of the ‘real’ India, or at least the ‘real India experience’ that travelers seek.

The slightly ambiguous ending can be taken in several ways, where we either view the revelations as a cop-out or a piece of a wish-fulfillment. It’s preferable to think of the conclusion as tending towards the latter, as it gives each of the players their own arc that reflects the mostly unseen Hannah’s voyage. As Béart’s character suggests, perhaps we are simply being led to a place we need to be.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2017 | New Zealand, India | DIR: Pan Nalin | WRITER: Diane Taylor | CAST: David Wenham, Emmanuelle Béart, Sia Trokenheim, Chelsie Preston Crayford | DISTRIBUTOR: Curious Films (NZ) | RUNNING TIME: 102 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 20 April 2017 (NZ), 25 April 2017 (Gold Coast Film Festival) [/stextbox]

2017 | New Zealand, India | DIR: Pan Nalin | WRITER: Diane Taylor | CAST: David Wenham, Emmanuelle Béart, Sia Trokenheim, Chelsie Preston Crayford | DISTRIBUTOR: Curious Films (NZ) | RUNNING TIME: 102 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 20 April 2017 (NZ), 25 April 2017 (Gold Coast Film Festival) [/stextbox]