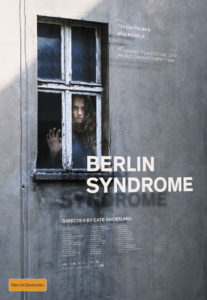

Cate Shortland’s Sommersault is one of the most acclaimed feature debuts in recent Australia cinema history, and her follow-up Lore is a beautiful and ethereal journey through a forgotten period of history. With BERLIN SYNDROME, director Shortland continues her German theme but in the far more traditional format of the psychological thriller.

Based on the novel by Melanie Joosten, the film follows photojournalist Clare (Teresa Palmer) as she arrives in Berlin for a life-changing bit of tourism. After a passionate affair with Andi (Max Riemelt), Clare awakens one morning in his apartment to find that she is unable to leave.

Tension is present at every turn in BERLIN SYNDROME. Even without the foreknowledge of what is coming, there’s no shortage of wolf totems, faux strangulations, locks, and Bryony Marks’ sinister atmospheric score to indicate that something isn’t quite right about Andi. Yet the slow-burning matter-of-factness to Clare’s predicament, and the relative happiness that they settle into during the first two-thirds of the film, is an intriguing approach to the subject matter.

Shortland’s trademark flashes of slow-motion, and a prominent use of natural and filtered light, emphasise the small beauties Clare begins to notice. Germain McMicking’s (Top of the Lake) photography is of a floating world, even if that means some occasionally disconcerting handheld. Andi’s fetishistic viewpoint is mirrored in McMicking’s lens, and this is intentionally uncomfortable and voyeuristic for the viewer. Yet thanks to the excellent work of Palmer and Riemelt, whose passionate clash of wills is only matched by the intimacy of their delicately shot lovemaking, we are nevertheless drawn in. Andi is initially charming after all, while Palmer may have mastered the subtle art of emoting entirely through her widened eyes.

It is a shame then that the back half of the film relies too heavily on familiar tropes, raising Clare’s (and the audience’s) hopes only to dash them repeatedly. A subplot involving Andi’s father takes us nowhere, except to restate that his relationship with humans is unusual at best. Much like its allusory title, the film draws us into a dangerous world and leaves us there long enough to normalise the behaviour, but never gives Clare or the audience the tools to escape the cycle. Despite its best intentions, BERLIN SYNDROME becomes the kind of closed-room thriller that we have seen far too many times before, where no pay-off will ever be as satisfying as the set-up.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2017 | Australia | DIR: Cate Shortland | WRITER: Shaun Grant (Based on the novel by Melanie Joosten) | CAST: Teresa Palmer, Max Riemelt | DISTRIBUTOR: eOne (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 116 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 20 April 2017 (AUS) [/stextbox]