While 2015’s Oscar winning Spotlight explored the journalistic investigation into child sex abuse in the Boston area by numerous Roman Catholic priests, Australia’s own disgraces had only recently been brought to light. The 2013 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse heard hundreds of tales of systemic cover ups of the crimes of child abusers.

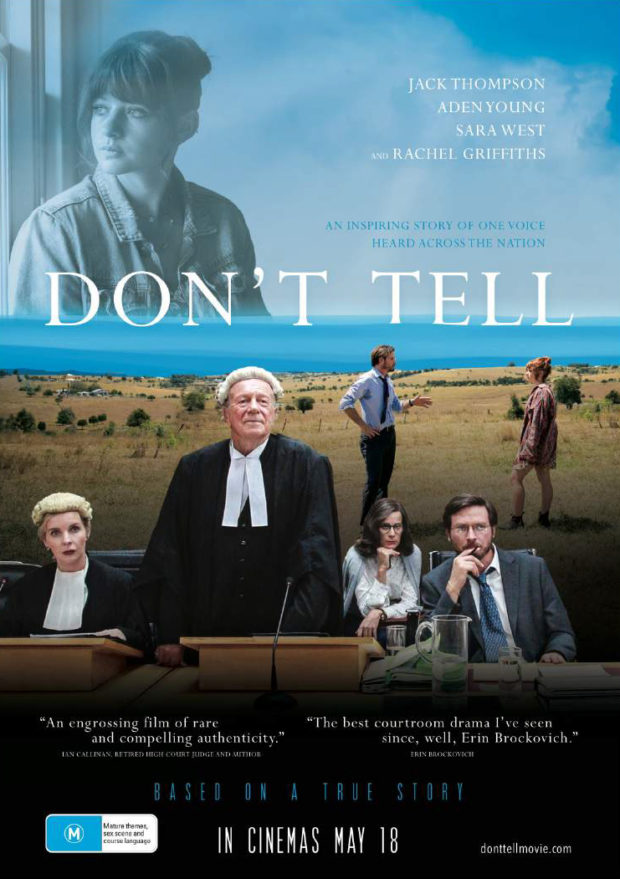

Over a decade before, lawyer Stephen Roche represented a young woman who was abused while in the care of an Anglican preparatory school. This landmark case formed the basis of his subsequent book, and the inspiration for director Tori Garrett’s debut feature DON’T TELL. Following the suicide death of a former client, Roche (Aden Young) is initially reluctant to involve himself in the case of the troubled Lyndal (Sara West), but together they doggedly take on the Church in a quest for justice.

Earnestly told, the strength of DON’T TELL is in its unwavering commitment to the notion of truth. A few bits of legal terminology notwithstanding, the story is told through the accurate lens of a legal procedural. Like an extended episode of Law & Order: SVU, albeit told in a far less formulaic manner, the reality of the adversarial system and unreliable witnesses play an important role in the pursuit of justice. Yet the structure of the film never allows the Chruch’s defence barrister (Jacqueline McKenzie) to become the villain of the piece, with that role falling on the administrators of Lyndal’s school and perhaps more broadly on the system at large.

Even with this courtroom setting, a result of the story being structured around a lawyer’s recollections, Garrett’s film allows plenty of opportunities for her leads to explore their characters. West, seen recently in episodes of Ash Vs Evil Dead, gives an award-worthy performance of the damaged Lyndal, equal parts fragile and fiery. The younger Lyndal, played at age 12 by Kiara Freeman, gets the benefit of cinematographer Mark Wareham’s (Jasper Jones) gorgeous shots of the Queensland countryside during wistful flashbacks. Aden Young’s understated performance brings real pathos to the characterisation, and works as a wonderful contrast to Jack Thompson’s warmly cantankerous barrister.

Other more subtle performances speak volumes as to why the culture of silence persisted for so long. Take Lyndal’s father, for example, who exhibits a taciturn guilt through his country-bloke barrier that is at the heart of a nation’s machismo. Her mother (the always wonderful Susie Porter) remained unaware of the clues Lyndal was sending out as a child. Yet these all form a kind of guidebook for noticing signs of abuse, the kind that can be easily misunderstood.

Which is where DON’T TELL becomes more than a simple narrative, and instead serves as a missive for standing up for those who slip through the cracks of an often inadequate system. Punctuated by the Missy Higgins song “Torchlight,” in which she advises “If anybody tells you not to tell, don’t listen,” it becomes an important film in helping victims understand their rights, and hopefully gives them additional strength to come forward and confront the criminals who abused them.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2017 | Australia | DIR: Tori Garrett | WRITER: Anne Brooksbank, Ursula Cleary, James Greville | CAST: Aden Young, Jaqueline McKenzie, Susie Porter, Sara West, Jack Thompson | RUNNING TIME: 108 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 18 May 2017 (AUS)[/stextbox]

Comments

2 responses to “Review: Don’t Tell”

Do see this, it is genuine cinema, not just a procedural. A rare Australian movie I’d be proud to show anywhere.

While government dithers over a national redress scheme, it can still find $11b in the budget for the religious schools that allowed these sex crimes. It ain’t right.

This film should be seen around the world, not as entertainment but for insight into the horror suffered by abuse victims and the moral abhorrence of institutional denialism.