“I’m a continuation of a particular kind of thread of human spirit,” mused artist Brett Whiteley in an interview, one of many to grace this superb new documentary on his life and art. As his voice is heard over a montage of his impressive career, it’s clear to see why he has continued to intrigue Australians and the world for almost half a century. Yet the real star will remain the art, writ large on the cinema screen and open to infinite reinterpretation.

After showing the record A$2.8 million sale of Opera House in 2007, director James Bogle takes us back to Whiteley’s more humble beginnings. Describing his upbringing as a “average to extraordinary middle class family into which god saw fit to throw a hand grenade,” we get a fairly intimate portrait of an artist as a young man.

From his boarding school origins, winning the 1959 Italian Scholarship, meeting future wife Wendy Julius, and the start of his recognition in London, we get a sense of how he developed a sense of personal style. Running parallel to this is the ‘cult of personality’ that grew in the art world, as the Sydney boy dove deeper into substance addiction, travelled the globe looking for meaning, and won multiple awards before returning to Australia. His death in 1992, in a motel room in Thirroul, was as incongruous of the rest of his existence.

As one would hope from a film about Whitetely, the film is presented in a visually engaging manner. During his childhood introduction to Van Gogh, for example, archival photographs transform into post-Impressionist recreations of Whiteley’s hometown. Similarly, actors portraying Brett and Wendy, along with other key figures such as their daughter Arkie, are intermingled with archival footage, photographs and interviews. We’re also lucky to have known Whiteley in the media age, with a plethora of footage including a generous number of interviews with Wendy Whiteley herself, and the 1989 film, Difficult Pleasure.

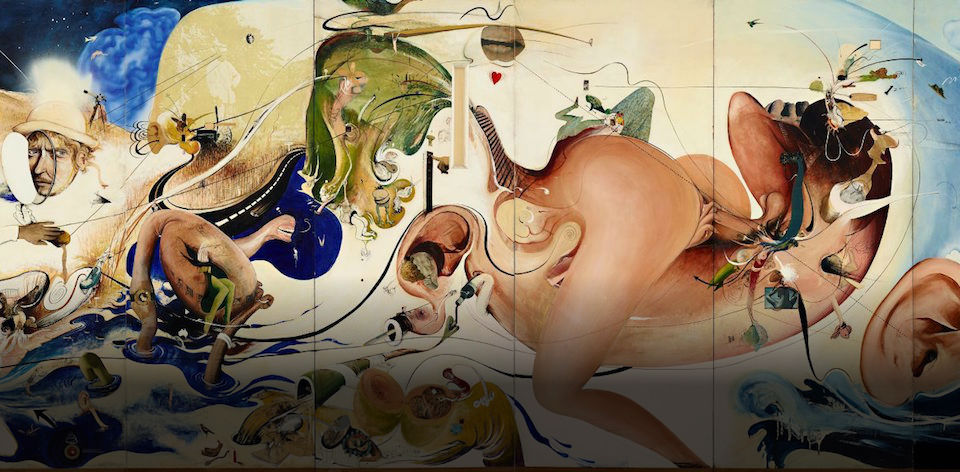

More than that, Bogle allows the work to speak for itself. While he may contextualise particular pieces, such as The American Dream (1968-69) within Whiteley’s low-point of addiction while living in New York (“I was deranging myself on booze and acid”), it merely serves to heighten the experience with the art. Whiteley’s sex life might be a curiosity in another work, but as the artist comments on the “erotic possibilities of the female form” in reference to his abstractions, Whiteley states that “my libido is as much a part of my works as ultramarine blue.” We certainly see this in his Bathroom Series, primarily focusing on the naked form of Wendy. Heightened by the zooms and pans of Bogle and cinematographer Jim Frater’s camera, the “idea of Wendy…drops away,” leaving the audience with a laser-focused appreciation of what’s right in front of us.

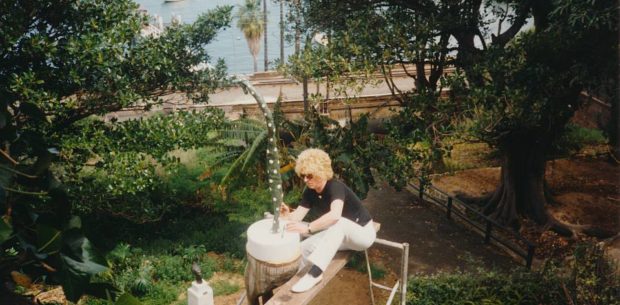

WHITELEY wraps up fairly promptly after covering his death, musing that his intensely personal work means we are still having a dialogue with him. Indeed, Sydney remains literally transformed for his presence, whether it is the towering matchsticks of Almost Once in the Domain, or Wendy Whiteley’s garden in Lavender Bay, where he once lived and worked. Sitting on the edge of crazed and genius, as all great artists do, Bogle’s documentary is an essential piece of art history that will leave you hungry for art in your life.

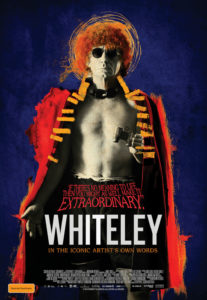

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2017 | Australia | DIR: James Bogle | WRITER: James Bogle, Victor Gentile | CAST: Brett Whiteley, Wendy Whiteley, Frannie Hopkirk | DISTRIBUTOR: Transmission Films| RUNNING TIME: 106 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 20 May 2017 [/stextbox]