Sofia Coppola’s distinctive style has weathered many formats over the last two decades behind the camera, from the coming-of-age drama The Virgin Suicides to the musical comedy of A Very Murray Christmas. With THE BEGUILED, the filmmaker turns her distinctive gaze to an adaptation of Thomas P. Cullinan’s A Painted Devil, one previously made into a film by Don Siegel. Here Coppola proves mastery of the Southern Gothic genre, bringing psychological warfare delicately to the forefront.

Several years into the American Civil War, a Southern girls’ boarding school under the care of Martha Farnsworth (Nicole Kidman) takes in wounded enemy soldier John McBurney (Colin Farrell) because it is the “Christian thing to do.” The sudden male presence in a house full of girls creates a minefield of sexual tension and mind games, one that begins cheekily enough but rapidly becomes melts into dark desire and personal gains.

Coppola’s film might be superficially seen as the flipping of the dominant gender paradigm, but a more interesting reading sees Coppola’s adapted script tearing strips off the facade of Southern hospitality. The civilised lessons led by Miss Edwina (Kirsten Dunst), and the almost parodic nature of the ornate dinners, drip away under the guile of the morally ambiguous houseguest. It’s wickedly delightful to see who turns darkest first.

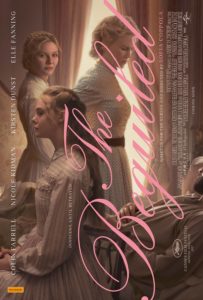

There’s something almost comical about the intensity of the prone Farrell’s flirtations, one that will undoubtedly elicit bursts of uncomfortable laughter from audiences. Counterbalanced by the uptight Dunst and the coquettish Elle Fanning, in a version of a role she has become adept at reinterpreting, giggles are eventually silenced by the unfolding horror of it all – not to mention the powerfully pragmatic gaze of the formidable Kidman.

With glorious naturally lit landscapes and chambers, this hypnotic and intoxicating vibe is in no hurry to get to its mic-drop conclusion. Even in the short running time, Philippe Le Sourd’s (The Grandmaster) camera finds time to linger on shafts of light across the Greek Revival columns that frame the architecture of the boarding school’s estate. The floating approach is aided by the presence of Phoenix’s notable score.

The deliberate use of the Civil War setting is a perfect backdrop, providing a realistic society without men and a rare point in US history where women had some modicum of dominance, albeit still in their corner of the world. Coppola transports Cullinan’s tale to her own ethereal plane, beguiling the audience with its beauty, and holding us captive with an understated horror that continues mounting until the very end.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2017 | US | DIR: Sofia Coppola | WRITERS: Sofia Coppola | CAST: Colin Farrell, Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, Elle Fanning | DISTRIBUTOR: Universal Pictures | RUNNING TIME: 94 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 23 June 2017 (US), 16 July 2017 (AUS) [/stextbox]