Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

LIVE AND LET DIE has the distinction of being a successful novel, a film, and a song that has been a success for two separate artists.

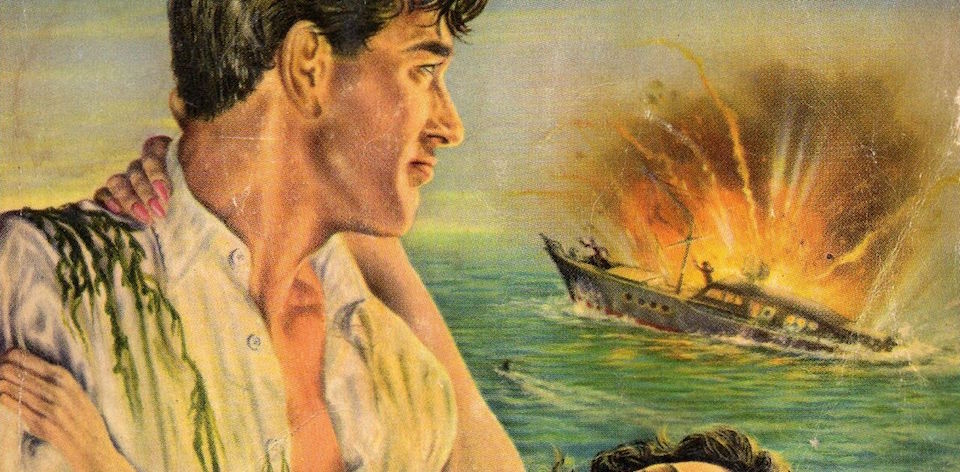

If you are young and your heart is an open book, then LIVE AND LET DIE might be considered the beginning of quintessential Bond. A consciously bigger story than Casino Royale, this globetrotting tale introduces many of the elements we associate with modern Bond, and indeed spy fiction generally.

In the second instalment of Bond’s adventures, we get a slight bit of a left turn with the introduction of a voodoo-based villain. Bond heads off to New York to investigate the night clubs of Buonaparte Ignace Gallia (a.k.a. “Mr Big”), a SMERSH operative/voodoo leader suspected of selling 17th-century gold coins as a means of financing Soviet spy operations in America. Sure, why not. The mission continues to Florida and the Caribbean, where Bond meets Solitaire, the female fortune teller in Big’s employ.

In this ever changin’ world in which we live in, the attitudes to race and sex are blessedly a far cry from where Fleming left them in the 1950s and 1960s when these books were penned. Fleming regularly falls back on racial stereotypes when describing his villains or the citizens of Harlem, something Andrew Taylor acknowledges in his introduction to the 2012 Vintage Classics edition.

After CIA companion Felix Leiter finishes explaining that he is down with the Harlem brothers (“I like the negroes and they know it somehow”), Fleming treats us to a number of interesting observations on the weird hierarchy of races that he would later build on. Even if you gave Fleming the benefit of the doubt and put it down to Bond’s rampant racism, there’s this gem from an interview few years earlier. “I believe that most black races have more fears than the whites,” Fleming wrote in the Spectator in 1952. “They are timid experimenters and inept or unwilling rationalisers of their fears and superstitions.” Really, Ian? Really?

Fleming’s general attitude to black characters is one of infantilisation (the almost impossible to read patois in the vein of “Mebbe git mahself a betterer gal”), villainy, or simply being called “Negroes,” “negroid,” or “Negresses” at various points. One chapter is titled “N***er Heaven,” and while it refers to a nightclub, it’s not something that modern readers will be comfortable with.

Mr. Big, on the other hand, is a different kind of villain to Bond’s later foes. Described as “grey-black, taut and shining like the face of a week-old corpse in the river,” he is also described as intelligent, but doesn’t display the ingenious insanity that some of Bond’s other adversaries have revelled in. Even if he does keep sharks for pleasure. “Mister Bond, I suffer from boredom,” explains Mr. Big. “I am prey to what the early Christians called ‘accidie’, the deadly lethargy that envelops those who are sated.” A slothful evil is a curious addition to the rogues gallery, but never one that rises above the ordinary.

Likewise, Solitaire is a paper thin love interest compared to Vesper Lynd and serves very little purpose. Apart from Vesper’s treachery, Solitaire is one of the first “birds with a broken wing” that Fleming is fond of drawing into Bond’s orbit. In this sense, she’s quintessential Fleming, but nothing more than a plot device. Indeed, like Vesper she is kidnapped by the villain’s minions, while one of the heroes is brutally tortured.

Unfortunately for Felix, he is the subject of Mr. Big’s torture this time around. Fleming had originally intended to kill off the character, but instead saw him lose and arm and a leg to Big’s sharks. (This gives us the wonderful and terrible pun “He disagreed with something that ate him.”) Felix survives, partly thanks to Fleming’s US literary agent, and continues to appear in novels as recent as Carte Blanche by Jeffery Deaver in 2011.

Despite some of these misgivings – at least some of which must be read with some sense of the era they were written in – when Fleming has got a job to do he’s going to do it well. Wielding sharp and brutal language, Fleming still manages to rip his way through an engaging tale. The people and the attitudes may be dated, but the formula is not.