The first peoples of Australia have long known of the power of the landscape, something cinema has only been exploring for just over a century. As a group of townsfolk watch The Story of the Kelly Gang in the streets, director Warwick Thornton reminds us SWEET COUNTRY is part of a long legacy of tales outlaws and injustices.

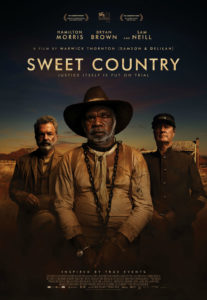

Thorton’s first dramatic feature since 2009’s Samson and Delilah is based on the similar story of Wilaberta Jack, delivered to Thorton by sound designer David Tranter. In the outback Northern Territory in 1929, Aboriginal stockman Sam (Hamilton Morris) kills the contemptible station owner Harry Marsh (Ewen Leslie) in self-defence. Sam flees with his wife Lizzie (Natassia Gorey-Furber), while Sergeant Fletcher (Bryan Brown) leads the posse of Aboriginal tracker Archie (Gibson John) and local landowners Fred Smith (Sam Neill) and Mick Kennedy (Thomas M Wright) to find him.

If this were a traditional western narrative, Thornton would rapidly put us on the trail of the fugitive and leave us there. Yet he and screenwriter Steven McGregor spend time on the contrasts of the nation, from the god-fearing Smith, striving for some kind of equality in a town without a church, to the casually cruel Kennedy, whose prejudice seems to be the product of societal conformity more than an innate malicious streak. This becomes clearer as his relationship with the mixed heritage boy Philomac (Tremayne Doolan) progresses.

Backed by Dylan River and Thornton’s stunning cinematography, also juxtaposing harsh deserts with beautiful rolling hills and purple sunrises, SWEET COUNTRY builds its tension primarily through the personality conflicts and subtle foreshadowing of the third act. As we near the inevitable conclusion, we realise that seemingly non-sequitur moments have been minor flash-forwards.

The film shifts gears to a minor courtroom drama with the arrival of Judge Taylor (Matt Day), and we become transfixed on the stunning lead performances of Morris and Brown in particular. Throughout the film, we have witnessed each character demonstrate their own notion of justice, perhaps as a microcosm of a country’s history. Like Taylor, SWEET COUNTRY is putting those ideas on trial.

SWEET COUNTRY, like Thorton’s documentary We Don’t Need a Map from earlier this year, looks to Australia’s past to ponder the future. It’s not always an optimistic portrait either, with the extreme prejudice of the town still alarmingly alive in modern Australia. There is no traditional western justice for the ‘hero’ of the piece, but that all might depend on what one’s notion of justice is after all. As Neill’s Fred Smith ponders, “What chance has this country got?”

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2017 | Australia | DIR: Warwick Thornton | WRITERS: David Tranter, Steven McGregor | CAST: Sam Neill, Bryan Brown, Hamilton Morris, Thomas M. Wright, Ewen Leslie, Gibson John, Natassia Gorey-Furber, Trevon Doolan, Tremayne Doolan, Matt Day, Anni Finsterer | DISTRIBUTOR: Transmission Films (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 110 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 25 January 2018 (ADLFF) [/stextbox]

2017 | Australia | DIR: Warwick Thornton | WRITERS: David Tranter, Steven McGregor | CAST: Sam Neill, Bryan Brown, Hamilton Morris, Thomas M. Wright, Ewen Leslie, Gibson John, Natassia Gorey-Furber, Trevon Doolan, Tremayne Doolan, Matt Day, Anni Finsterer | DISTRIBUTOR: Transmission Films (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 110 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 25 January 2018 (ADLFF) [/stextbox]