Bond. James Bond. Is there a name more synonymous with spying, tuxedos, and shaken cocktails than the British secret agent? Join me as I read all of the James Bond books in 007 Case Files, encompassing Ian Fleming and beyond. For Your Eyes Only: there’s potential spoilers ahead.

Before anything else, Ian Fleming wants us to know that he knows his stuff. In an author’s note, he humblebrags “Not that it matters, but a great deal of the background to this story is accurate.” He’s not wrong: whether we can truly ever know the ins and outs of spycraft in the 1950s, his world here feels authentic.

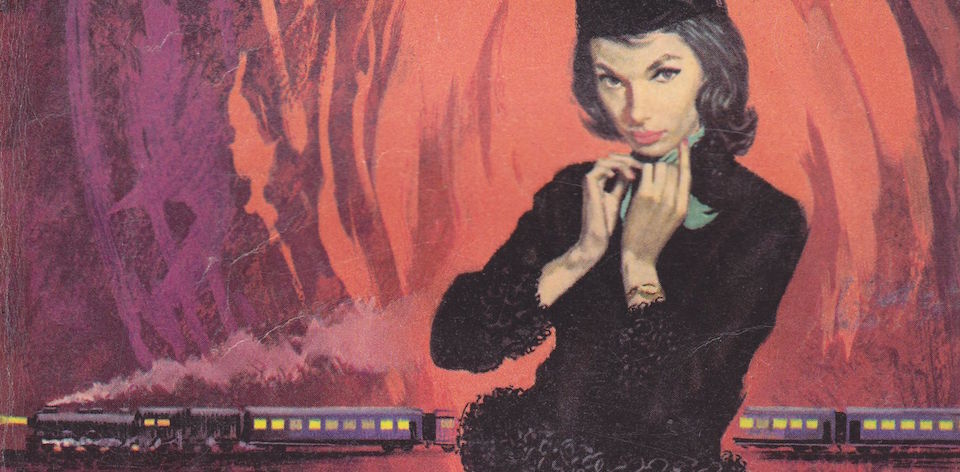

As the fifth book in Fleming’s series, it’s unquestionably his most mature at this point and one of his most ambitious projects. It’s also one of his longest. Split into two parts, it’s well over 100 pages before Bond is introduced. Instead we spend most of our time getting to know SMERSH executioner Red Grant, a western defector who has the sole pleasure of killing for any side; Tatiania Romanova, a cipher clerk who pretends to defect in order to woo Bond; and Colonel Rosa Klebb, the person pulling both their strings. It’s almost as if Fleming was less interested in Bond at this point than he was with the world he’d created around him.

Indeed, when Bond is eventually introduced, even he is tiring of his lavish lifestyle. Having parted ways with the complex Tiffany Case from Diamonds Are Forever, 007 feels that he has gone soft. As if to prove this to readers, he’s totally suckered in by Tatiania’s beguiling ways. To some extent, it mirrors his involvement with Vesper Lynd in Casino Royale but narrowly avoids repetition.

Yet there’s the pervasive attitudes Of The Time that rear their ugly heads throughout this. Romanova is one of the more infantilised “Bond Girls” to date, with he role landing somewhere between sex object and McGuffin. While various people of colour escape Fleming’s 1950s eye, his attitudes towards sexuality are ever-present here. “Homosexuals,” according to one person at a staff meeting, “were about the worst security risk there is. I can’t see the Americans handing over many atom secrets to a lot of pansies soaked in scent.“

Rosa Klebb seems to personify this attitude, with Fleming heavily implying that she is a lesbian. Robbed of any gender upon introduction, Klebb is described as “a toad-like figure in an olive-green uniform which bore the single order of Lenin.” Later she appears wearing some unfortunate lingerie. As Nicholas Lezard points out in an article for The Guardian, “Fleming poured all his disgust – and he had plenty – into his creation.“

Leaving us on an unexpected bummer of an ending, FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE is still one of Fleming’s most unusual and satisfying books overall. At times heavily influenced by other works of fiction, including a murder on the Orient Express in the final act, you can see Fleming playing around the edges of something new behind the scenes. That alone make it stand out from the four books that preceded it.

More than anything, FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE is a contradiction: it is both a product of a bygone Cold War era while fully tapping into the zeitgeist of current US-UK-Russian relations. At the time of writing this review, diplomats around the world are being expelled from embassies in retaliation to the poisoning of a former Russian spy and his daughter in Britain. So to paraphrase Fleming, while the fictional worlds of a chauvinistic spy may not matter, a lot of it is accurate.