There’s an Instagram account of found locations called Accidentally Wes Anderson. Aside from being hilarious, it’s a recognition of the atypical and symmetrical aesthetic that has become synonymous with the filmmaker. So of course, while the global community copies and continues to be entranced by Anderson’s world, with ISLE OF DOGS he has created something entirely new. Based in a love of Japanese culture and cinema, it just might be his masterpiece.

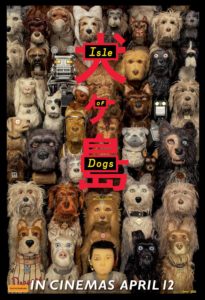

In the not-too-distant future of Japan, Mayor Kobayashi (Kunichi Nomura) reacts to a dog flu epidemic by banning all canines to a nearby island. The young boy Atari (Koyu Rankin) goes searching for his dog with the help of dogs Rex (Edward Norton), King (Bob Balaban), Boss (BIll Murray), Duke (Jeff Goldblum), and the reluctant Chief (Bryan Cranston).

ISLE OF DOGS is a curious piece to make in the current climate. Following Lost in Translation from his contemporary Sofia Coppola (and whose brother Roman gets a story credit on this film), or last year’s controversial Death Note, accusations of cultural tourism are never far beneath the surface. Anderson’s film certainly ticks off many of the cliches of an outsider’s view of Japan, opening with taiko drummers and a haiku, later throwing in a sumo wrestler or two for good measure. Taken by themselves, they are harmless shorthand references that continually remind us of the distinctive setting. It’s not meant to be any more representative of real Japan than The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou was of divers.

Complicating matters is the character of Tracy Walker (Greta Gerwig), a foreign exchange student and activist whose path skirts along the edge of a white saviour narrative. So there’s a small part of us that wonders if Anderson’s film is bordering on cultural appropriation here. From the start, Anderson is careful to point out that while the dogs are speaking English, that’s just because it’s the filter he’s chosen. All other Japanese characters speak in their native tongue, and this goes largely untranslated. At worst its a homage to a bygone era in Japan, interpreted through the quirky lens of an American filmmaker. In other words, it’s another one of Anderson’s aesthetic anachronisms.

So taken as a visual and narrative tribute to classic Japanese cinema, including obvious influences from Studio Ghibli and Akira Kurosawa, Anderson is recreating something that could have happily been released in Japan in the 1960s or 1970s. A triumph in animation, every moment on screen is a study in the painstaking process of stop-motion. A pack of dogs fighting over scraps is a cartoony cloud of limbs and paws. At other times, blood gruesomely and hilariously spurts out of the side of Atari’s injured head. Dogs act like dogs when you least expect it. Lingering zooms on characters or fourth-wall camera turns could have happily sat alongside anything in Moonrise Kingdom.

All of it is designed to fuse Anderson’s distinctive style with frame-by-frame nods to everything from Akira to Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel. “The tone we were always going for was ‘20 years in the future,” said production deisgner Paul Harrod in an interview with Atlas Obscura. “But it’s not 20 years in our future, it’s more like 20 years from about 1964.” Television sets and studio equipment look ancient, but there’s a style that mirrors Walt Disney’s mid-century theme park version of what Tomorrowland. Broadcast footage uses traditional 2D animation in black and white, and is coupled with anti-dog propaganda posters that could have been designed by Keiji Nakazawa.

Peppered with a stream of one-liners, and a voice cast that’s to die for, ISLE OF DOGS is one of Anderson’s most consciously funny films to date as well. Like Fantastic Mr. Fox, his previous stop-motion animated film, Anderson uses the medium to give the audience just enough separation from a gruesome tale to still enjoy the insanity of it all. The dynamic duo of Jupiter and Oracle (F. Murray Abraham and Tilda Swinton) are priceless.

So while some filmmakers incorporate the cool facade of a culture and never get beneath the surface, Anderson’s animated film manages to have its cake and eat it too. This is a heartfelt tribute to cinema that is fully aware of the legacy that preceded it. These dogs may not have masters, but the film might just have mastered our hearts.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2018 | US | DIRECTOR: Wes Anderson | WRITERS: Wes Anderson (screenplay), Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, Kunichi Nomura (story by) | CAST: Bryan Cranston, Edward Norton, Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum, Bob Balaban, Kunichi Nomura, Ken Watanabe, Greta Gerwig, Frances McDormand, Fisher Stevens, Nijiro Murakami | DISTRIBUTOR: 20th Century Fox (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 101 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 12 April 2018 (AUS) [/stextbox]