This was always going to be a difficult adaptation. Tim Winton’s intimate narrative of two young boys and their relationship with an older surfer and his wife is two parts surfer’s soul, and a shot of something more reckless. Filtered through the lens of nostalgia, Winton’s dark glass gets re-examined by co-writer/director Simon Baker, applying his own interpretation to what is often troubling subject matter.

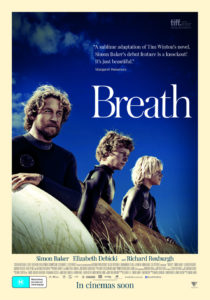

In a small town in the 1970s, young boys Pikelet (Samson Coulter) and Loonie (Ben Spence) form a relationship with Sando (Baker), and older man who live with his partner Eva (Elizabeth Debicki). As their relationship grows, he pushes the friends to take ever increasing risks, drawing them in different directions and testing the limits of their fear.

The title of Winton’s 2008 novel comes from a recurring motif in the text, with an almost reverential attitude to breathing. Pikelet’s dad (an underused Richard Roxburgh) snores in his nocturnal gasps for breath, and Pikelet has the breath knocked out of him on the back of a wave. In the present day, he literally gives breath to people as a paramedic. There is a reverence to the simple act of breathing. Yet Baker excises Winton’s bookends for the most part, leaving us with an oddity of a story.

The measured pacing of the first part of Winton’s book forces the reader to slow down and acknowledge each inhalation and exhalation that the text takes. It’s like Pikelet’s on-screen observation of watching his companions on the waves: “Never had I seen men do something so beautiful.” Baker takes this to extremes by playing out most of the film as long shots of surfing, or thinking about surfing. “If we weren’t with Sando, then we were just marking time,” narrates Pikelet, inadvertently making a bit of meta-commentary on the film’s measured plotting.

The sharp turn in the back half of film is foreshadowed in the novel multiple times, but here Gerard Lee and Baker’s script lobs it in like a hand grenade. Yet where it leaves the reader is less predictable, turning a gently whimsical tale into something darker and more heartbreaking. The introduction of autoerotic asphyxiation and an illicit affair were always going to need the most delicate of touches. Instead, Baker gives us a montage of eroticised paedophilia set to Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain,” the same song used to battle a sentient planet in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.

The broader brushstrokes of risk, recklessness, and reward don’t translate to the screen. A brief coda, foreshadowed by sporadic Wonder Years style narration, tries to replicate Pikelet’s adult reflections on his life. Yet instead of a moral tale of a boy finding the limits of his own ordinariness, we get something that never takes any of its own risks. The film has all the trappings of building up to a deeper payoff, but if you’re waiting for an easy resolution, don’t hold your breath.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2018 | Australia | DIRECTOR: Simon Baker | WRITERS: Gerard Lee, Simon Baker (Based on the novel by Tim Winton) | CAST: Simon Baker, Elizabeth Debicki, Samson Coulter, Ben Spence, Richard Roxburgh | DISTRIBUTOR: Roadshow Films(AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 115 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 3 May 2018 (AUS) [/stextbox]

2018 | Australia | DIRECTOR: Simon Baker | WRITERS: Gerard Lee, Simon Baker (Based on the novel by Tim Winton) | CAST: Simon Baker, Elizabeth Debicki, Samson Coulter, Ben Spence, Richard Roxburgh | DISTRIBUTOR: Roadshow Films(AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 115 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 3 May 2018 (AUS) [/stextbox]