Even comic books took a while to have crossovers.

As hard as it is to believe, for the first 13 years of their shared publication history, Superman and Batman never teamed up on panel. That would, of course, change with World’s Finest and Justice League of America. Marvel, on the other hand, made teams their thing during their modern inception. They kicked off 1961 with Fantastic Four, and followed with X-Men and the Avengers over the next few years.

Cinematic adaptations have always preferred the solo approach. Largely stuck in the origin story and sequel cycle, studio sentiment seems to assume that audiences can only remember things that happened within the last 2 hours of their lives.

Which is what makes the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) and Avengers: Infinity War such a monumental achievement. Over the course of 10 years and 19 films, Marvel Studios has not only mirrored the serialised storytelling of comics, but readjusted audience expectations about what a film series can be. Here we look at the very long road to Avengers: Infinity War on screen.

Killer serials

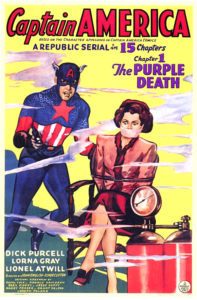

This 1944 serial was Marvel/Timely’s first licensed film – and was very different to the source material.

Serial film is nothing new, of course. Old school cinema punters would typically rock up to a Saturday matinee with at least one serial chapter, a handful or cartoons, and potentially a double feature. Even in the silent era, shows like The Perils of Pauline perfected the art of the cliffhanger ending.

During the Golden Age of cinema, some of the leading lights in serial films were based on superheroes. Flash Gordon, The Green Hornet, The Phantom, Dick Tracey, The Batman, and Captain Marvel, were just some of the serialised films running between the 1930s and the 1950s.

In fact, this period saw the first Marvel (then called Timely Comics) characters on screen in the Captain America (1944) serial, the first example of the company licencing out their characters for the money. Never mind that Cap is depicted as District Attorney Grant Gardner, carried a gun instead of a shield, and was trying to stop evil from getting their hands on the “Dynamic Vibrator.” Insert your own joke here. This was the start of cinema history.

Television: the original Netflix and thrill

So then television kind of replaced the whole cinematic serial thing for a while. With the exception of that Captain America serial in the 1940s, one that ended with the untimely death of lead actor Nick Purcell, Marvel kept the majority of their adaptations on the small screen prior to the 1980s. Along with the animated offerings of the 1960s and 1970s, there were blended efforts like Spider Super Stories from the Electric Company. In 1977, Marvel dropped the double-whammy of Spider-Man (starring Australia’s Nicholas Hammond) and The Incredible Hulk (with Bill Bixby and Lou Ferrigno) as their two most successful live-action series to that point. It didn’t start a TV universe, but we did get random cameos from Daredevil, Thor, and of course, Stan Lee. Of the era, the 1978 Dr. Strange film is strangely good as an origin story. 1979’s Captain America and Captain America II: Death Too Soon…not so much.

So then television kind of replaced the whole cinematic serial thing for a while. With the exception of that Captain America serial in the 1940s, one that ended with the untimely death of lead actor Nick Purcell, Marvel kept the majority of their adaptations on the small screen prior to the 1980s. Along with the animated offerings of the 1960s and 1970s, there were blended efforts like Spider Super Stories from the Electric Company. In 1977, Marvel dropped the double-whammy of Spider-Man (starring Australia’s Nicholas Hammond) and The Incredible Hulk (with Bill Bixby and Lou Ferrigno) as their two most successful live-action series to that point. It didn’t start a TV universe, but we did get random cameos from Daredevil, Thor, and of course, Stan Lee. Of the era, the 1978 Dr. Strange film is strangely good as an origin story. 1979’s Captain America and Captain America II: Death Too Soon…not so much.

READ MORE: The evolution of Spider-Man on screen: 1960s – 1990s

The road to Marvel Studios

Prior to 2008, Marvel really had no interest in world-building. Much like the comics themselves, the early superhero blockbusters were all about solo adventures. The Marvel Entertainment Group (MEG) of the 1970s and 1980s really only produced two films of note: Howard the Duck (1986) and The Punisher (1989), neither of which connected with audiences. There was a 1990 version of Captain America, and the small screen Nick Fury: Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. (1998) starring David Hasselhoff. Yet perhaps the most infamous is Roger Corman’s 1994 Fantastic Four: it was made but never intended to be released.

By 1997, Marvel Studios was doing two things: licensing out characters, and pumping out solo films. In this era, we got the likes of Blade (1998), X-Men (2000) and its sequels, Spider-Man (2002), Daredevil (2003), Elektra (2005), and Fantastic Four (2005). What we didn’t get was any sense of connectivity. The best we could hope for is a newspaper headline or a cameo that hinted at a world beyond the central protagonist. This would change under the Kevin Feige era at Marvel Studios.

Serial event cinema

NB: This section of the article expands on some previously published ideas on the site.

Enter modern Marvel Studios. We won’t waste your time talking about all the legal wranglings that got the studio to the point, or the crazy amount of licensing that left Marvel’s characters estranged and adrift at the various studios around Hollywood. There’s whole Wikipedia articles on that. What’s important is that Marvel Studios began a concerted effort to unify the properties they had under their control. More importantly, it marked a change in the way a major studio was approaching storytelling, stepping away from the singles and doubles approach of a successful solo franchise and a possible sequel or threequel.

When Marvel Studios first launched Iron Man in 2008, it could have all ended there. There was a brief post-credits sequence that introduced Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson) and his idea for the “Avengers Initiative.” If Iron Man flopped, it would have been a fun Easter egg. Except that it didn’t, and that small reference turned into a multi-hero adventure in Iron Man 2 (2010). The remainder of the Phase One films, as we now know them, were strictly solo adventures, occasionally teasing what would happen next. Yet when they culminated in Joss Whedon’s Avengers (2012), cinema audiences saw something on screen that had literally never been done before.

What followed is perhaps even more remarkable. The confidence to expand the Marvel Universe led to even more interesting properties being introduced to cinema audiences. In a bygone era, Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), Ant-Man (2015), or Doctor Strange (2017) would have been a couple of crazy studio outings that critics and audiences half-expected to sink without a trace. Under the auspices of the Marvel Cinematic Universe they became stepping stones to a bigger story, where the smallest of characters (literally in the case of Ant-Man) could have a huge impact in a later entry. Even the traditional sequels – Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), Captain America: Civil War (2016), and to some extent Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017) – were as much about the lead characters interacting with a wider world of heroes and villains than they were about a solo resolution.

Comic books as movies

The success of these films relies in part on their storied comic book history. The very fact that decades of Marvel Comics exist allows for a certain amount of shorthand in cinematic storytelling. In Spider-Man: Homecoming, Marvel dispensed with the origin story entirely for a reinterpretation of a Millennial Peter Parker who grew up in the shadow of Tony Stark and his tower. This was also possible thanks to the many previous appearances of Spidey on screen, and the well structured universe Marvel had created around him. 2018’s Black Panther followed a similar route, acting as the connective tissue between Captain America: Civil War and Avengers: Infinity War.

READ MORE: Reviewing the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Yet as the films start to mirror the comic book formatting even more closely, with regular biannual installments punctuated by events, the Marvel Cinematic Universe begins to carry some of the weight of its printed counterpart’s woes. The comic books themselves have become so impenetrable that publishers are constantly looking for new tactics to draw in increasingly dwindling audiences, drawing criticism for endless reboots and crossovers. These blockbuster films are not giant advertisements for the comics, but instead offer a streamlined version of continuity that highlights the printed industry’s outdated practices.

In this vein, the MCU has now become the pinnacle of serialised storytelling. What we have with the MCU is a reversal of the Golden Age model: the serial is the main event, leaving everything else as a B-feature in its wake. Marvel is so confident of this storytelling model that they are willing to leave us on a cliffhanger at the end of Avengers: Infinity War and release two prequels (Ant-Man and the Wasp and Captain Marvel) in the interim. While this might put some additional burden on the audience, asking them to remember plot points from almost two dozen films, it’s rare that the storytelling relies on excessive prior knowledge – it’s just enhanced by it.

The MCU will continue to grow and evolve past the (as yet untitled) fourth Avengers film. Some of the films are confirmed, while others are the subject of rampant speculation. While it isn’t the be-all and end-all of filmmaking, the box office takings continue to indicate that audiences are returning for the ride and the numbers of them are growing. The whole franchise is a bit like a cinematic whale, with audiences slowly attaching themselves like so many plankton to the unstoppable behemoth. Fears of comic book fatigue are yet to manifest at the box office, and perhaps that is because Marvel has created something that isn’t just a transactional encounter. It’s an emotional investment.