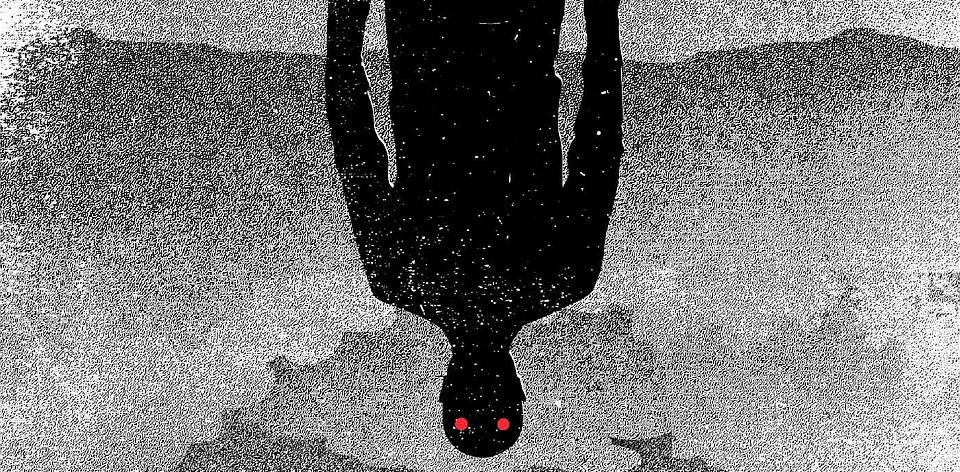

If Stephen King was a favourite cardigan, it would be one that was a comfort to slip into but always left you worried that it might eat your childhood at moment’s notice. With THE OUTSIDER, King reminds us of his mastery of the macabre and his ability to rapidly shift gears between genres.

As King’s first solo novel since 2016’s End of Watch, the constant writer’s slow-building tension draws us into a world that is both alien and familiar. In the fictional town of Flint City, Oklahoma, a boy is brutally assaulted and murdered. Police detective Ralph Anderson arrests teacher and Little League Baseball coach Terry Maitland in an incredibly public setting, instantly causing a media circus. All the physical evidence points to his guilt, but he has an airtight alibi of being out of town.

Like the Bill Hodges Trilogy (Mr. Mercedes, Finders Keepers, End of Watch), King initially constructs THE OUTSIDER as a police procedural. A kind of locked-room mystery is presented from the outset, with the real puzzle beginning with the discover of Terry’s inter-state trip to see author Harlen Coben speaking at a conference. The plot device serves two purposes: to introduce the notion of doubles or ‘others’, and to signal to readers that the literate King is well aware of the existing masters of the turf he’s playing in. Yet this is where King is at his strongest, holding our attention as a myriad of characters are introduced, giving us a reason to care about each one.

When a recognisable name or two pops up in the second half of the book, a moment that actually made this Constant Reader gasp out loud, the book begins to take its turn into the supernatural. While it is not for this reviewer to reveal any more of the plot, suffice it to say that the narrative finds a heartfelt hook that both lightens the tone and deepens the connection to the imaginatively mysterious. Perhaps the nearest comparison is King’s own masterpiece ‘Salem’s Lot, where disparate threads and characters put aside their natural antagonisms and slowly come together to fight an evil presence.

By the same token, this genre turn will inevitably recall a number of King’s past works, and evoke a certain sense of been-there-done-thatness. Indeed, his previous release of Sleeping Beauties (co-written with son Owen King) had a much more nuanced and morally ambiguous set of misfits. Even so, King remains sharply contemporary in most of his references, the odd anachronistic musical choice notwithstanding. The whole notion of ‘otherness’ has parallels with the culture of fear that has crept (read: stormed) into popular discourse. The media blitz around Terry Maitland is the kind of behaviour that makes major networks the target of ‘fake news’ labels from a certain 45th President of the United States. Speaking of which, there are several not-so-subtle digs at Trump, and it’s nice to see that King’s well publicised political convictions can sit happily alongside his authorial ones.

As the final act rolls around, message boards and the GoodReads comments sections will be ablaze with theories about connections to other works. Perhaps King is aware of this when one of his characters remarks “If you can’t let go of the past, the mistakes you’ve made will eat you alive.” King will inevitably remain coy about the subject – after all, he’s still not willing to be definitive about The Dark Tower connections of last year’s Gwendy’s Button Box, a book that has a mysterious man in black with the initials R.F. and who likes to “palaver.” Nevertheless, as THE OUTSIDER wraps up, there’s little doubt that this could sit happily alongside any of King’s more recent canon as a fine example of a taut page-turner.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”]2018 | US | WRITER: Stephen King | PUBLISHER: Hodder & Stoughton | LENGTH: 477 pages | RELEASE DATE: 22 May 2018 (AUS) [/stextbox]