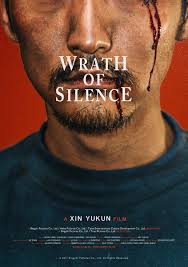

Following the acclaimed The Coffin in the Mountain, director Xin Yukun’s THE WRATH OF SILENCE is sure to have challenged the infamous Chinese censors. Not only does it combine a slick mix of noir, western, and modern thriller, but it is less than flattering in its depiction of the impact of corrupt mining magnates on the lives of rural workers.

We’re introduced to the village around Gufeng Mountain via worker Zhang Baomin (Song Yang), who returns home to learn that his son has gone missing. Having already become a town pariah due to his roughhousing ways, not to mention being the last holdout in signing a mining contract, his search is not easy. Complicating matters is his lack of a voice, having lost the ability to speak during a youthful indiscretion.

Baomin’s outlook has all the hallmarks of a spaghetti western, caught in the middle of powerful interests, but with his own agenda at play. His search soon crosses paths with tycoon Chang Wannian (Jiang Wu), who recalls the villains of Chinatown, and a lawyer who’s own daughter has been kidnapped. This simple revenge dynamic would be just an average thriller were it not for Xin’s impeccable and film literate execution.

The finely detailed sets are shot by cinematographer He Shan, who is unforgiving in his vision of the moral decay of the elite classes. A recurring motif shows Chang slurping his food in extreme close-ups – tomatoes, copious piles of meat – and serve as a visual shorthand for his villainy. Then there’s the widescreen shots of the mountainside, excavated within an inch of its life, juxtaposed with the unforgiving concrete of the city. Backed by Sylvian Wang’s perpetually foreboding score, it’s a living nightmare that Baomin must navigate.

Song, no stranger to action from The Final Master, has some magnificent moments of action on screen. Taking a cue from 1980s Hong Kong action, fight sequences are hand-to-hand affairs using objects from the surroundings. A major melee between miners is all pipes and shovels, while a penultimate office showdown is knowingly comical in its over-the-top destruction of safe work practices and stationery.

The heavy-handed way in which the denouement plays out certainly undercuts some of the subtlety of the lead-up. Yet there’s a delicate interplay between death and life that could possibly only work in the unique context of Chinese rural life. So for all of its foreign influences, Xin’s thriller is ultimately something that reinforces a traditional belief and a victory for the common people. That should please those censors immensely.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2017 | China | DIR: Xin Yukun | WRITER: Xin Yukun | CAST: Song Yang, Jiang Wu, Yuan Wenkang | DISTRIBUTOR: Fortissimo Films, Sydney Film Festival (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 126 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 8 June 2018 (SFF) [/stextbox]

2017 | China | DIR: Xin Yukun | WRITER: Xin Yukun | CAST: Song Yang, Jiang Wu, Yuan Wenkang | DISTRIBUTOR: Fortissimo Films, Sydney Film Festival (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 126 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 8 June 2018 (SFF) [/stextbox]