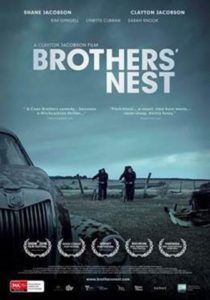

It’s been a staggering 12 years since the massive success of the mockumentary Kenny, and with BROTHERS’ NEST, director and actor Clayton Jacobson reunites with his brother Shane Jacobson for what is a very different film.

On a cold morning somewhere in the middle of country Victoria, brothers Terry (Shane Jacobson) and Jeff (Clayton Jacobson) arrive at their mother’s family home in forensic garb. Ultimately out to change the mind of their dying mother (Lynette Curran), who plans to favour their stepfather Rodger (Kim Gyngell) in her will, it soon becomes clear that their intent is far more cynical.

The most immediate comparison this film is going to get is to the early work of the Coen Brothers. It’s not just the familial motif either, with Clayton Jacobson working hard to imbue the film with a moody tension that recalls Blood Simple. Peter Falk’s lensing is a slate blue affair, ensuring the audience feels the frost of a Victorian morning.

Despite this familiarity, Jaime Browne and Chris Pahlow’s script keeps us guessing right up until the end. We always suspect there is something more going on than a mere robbery, but the truth is even more sinister than we could have suspected. Dropping in hints and bits of misdirection, such as Terry’s affinity to a family horse, gives us sense that we are only seeing the tip of a much larger narrative under the surface. An appearance of an almost unrecognisable Gyngell shifts the tone significantly, resulting in a dark comedy of errors that continues the Coen connection.

After a slew of comedies, including The BBQ and That’s Not My Dog this year alone, Shane Jacobson takes a welcome sidestep into drama. His typically affable personality allows us to believe his reluctance to take part in Jeff’s scheme. There’s also some emotional baggage sitting behind his portrayal, a relationship with a father that is mostly hinted at throughout. Clayton Jacobson provides a perfect counterpoint, a controlled anti-villain who makes us switch allegiances on a regular basis.

BROTHERS’ NEST is a film that doesn’t stray too far from the genre favourites that influenced it, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The final few scenes are telegraphed from the beginning, a little indulgent flourish that doesn’t undermine the end so much as put it in familiar company. Regardless, this is a sophisticated direction for both of the Jacobson boys, and certainly a path down which we would love to see them take more often.

[stextbox id=”grey” bgcolor=”F2F2F2″ mleft=”5″ mright=”5″ image=”null”] 2018 | Australia | DIRECTOR: Clayton Jacobson | WRITERS: Jaime Brown, Chris Pahlow | CAST: Shane Jacobson, Clayton Jacobson, Lynette Curran | DISTRIBUTOR: Label Distribution (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 97 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 3 May 2018 (AUS) [/stextbox]

2018 | Australia | DIRECTOR: Clayton Jacobson | WRITERS: Jaime Brown, Chris Pahlow | CAST: Shane Jacobson, Clayton Jacobson, Lynette Curran | DISTRIBUTOR: Label Distribution (AUS) | RUNNING TIME: 97 minutes | RELEASE DATE: 3 May 2018 (AUS) [/stextbox]